He scribbled drawings mocking the Kremlin. Daniil Kliouka has since been thrown into the depths of the Russian prison system for many years. Where violence imposes its silence and where the traces of detainees sometimes disappear.

His story is just one example among many in Russia, in the midst of repression of any resistance, real or imagined, to the invasion of Ukraine.

Until the winter of 2023, this 28-year-old Russian plastic arts teacher led a peaceful existence in Dankov, a town located 300 kilometers south of Moscow, not far from the station where the writer Leo Tolstoy died.

On the website of his old school, an ordinary establishment, you can see photos of his classroom with reproductions of paintings on the walls, including a self-portrait by Van Gogh.

His life collapsed in February 2023 when he was arrested in Dankov by hooded agents of the FSB, the formidable Russian security services.

They accuse him of having sent 135,000 rubles (around 1,280 euros at the current rate) in cryptocurrency to the Ukrainian ultranationalist Azov brigade, classified as “terrorist” in Russia. Accusations he denies.

Daniil Kliouka says it all started when his director reported him to the FSB for sketching little anti-power drawings on a newspaper.

The AFP was able to reconstruct his descent into hell after learning the content of letters he exchanged with a Russian anti-war activist living in exile in Italy.

Antonina Polichtchouk, 43, gradually brought this affair out of the shadows from August 2023, thanks to a project encouraging epistolary relations with political prisoners who, even prosecuted for the most serious crimes, have a right of correspondence .

Originally, she chose to talk with Daniil Kliouka because he wanted to talk about architecture and Japanese cartoons. “I am interested in architecture and my daughter is interested in Japanese cartoons, I said to myself that we could write to her together,” explains Ms. Polichtchouk.

Through letters exchanged via the official online platform of the prison administration, she discovered that the young man was being prosecuted for “high treason” and “financing a terrorist organization”.

Crimes, very severely punished, of which the Russian state regularly accuses its supposed enemies in order to crush them.

– Drawings of “mustaches” –

Daniil Kliouka claims to have been the victim of a denunciation. A process popular in Russia and encouraged by the authorities, like President Vladimir Putin who, from March 2022, called for the removal of “traitors” and the “self-purification” of society.

Activist groups, such as the “Veterans of Russia” organization led by Ildar Reziapov, have made it a specialty and denounce hundreds of people publicly and to the prosecutor's office.

Simple citizens or minor officials denounce a neighbor or colleague out of conviction, ambition, greed, jealousy or simple antipathy.

Daniil Kliouka said that in his spare time, at his workplace, he drew “horns, beards and mustaches” on photos in a local pro-Kremlin newspaper.

“When there were representatives of power on a page, I sometimes wrote 'demon' on their foreheads,” he said in a letter published by the Telegram group Politzek-Info, covering political repressions.

But one day he forgot the newspaper at school and his colleagues came across it.

According to him, for these scribbles, his director fired him and contacted the FSB. He said he was then arrested, tortured “in a cellar” and that his home was searched.

It was in his phone confiscated at his home that the agents found the evidence, according to them, of the suspicious transfers.

Daniil Kliouka claims to have made a false confession and admitted under the blows to having sent funds to the Azov brigade. Before declaring in his letters, once in detention, that he had in fact transmitted money to a Ukrainian cousin.

The cousin, Mykyta Laptiev, confirmed having received this money and assures that it was used to treat his father, Daniil Kliouka's uncle.

Contacted on social networks, the school manager whom the teacher accuses, Irina Kouzitcheva, did not respond to requests from AFP.

It is also impossible to compare the prisoner's statements with those of the prosecution because the FSB classified the procedure as secret, as almost always in this type of case. His defense is prohibited from discussing the case, under penalty of prison.

– “To scare” –

After six months of correspondence, activist Antonina Polichchouk realizes that Daniil Kliouka only has a court-appointed lawyer who “de facto works for the government”.

“His family could have paid a lawyer and taken care of it, but their situation is complicated, they were intimidated. The FSB scares everyone,” she laments.

At his request, the human rights organization Memorial, co-winner of the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize, banned in Russia but active in exile, is paying for a new council. Antonina Polichtchouk creates a prisoner support group on Telegram, followed by 200 people.

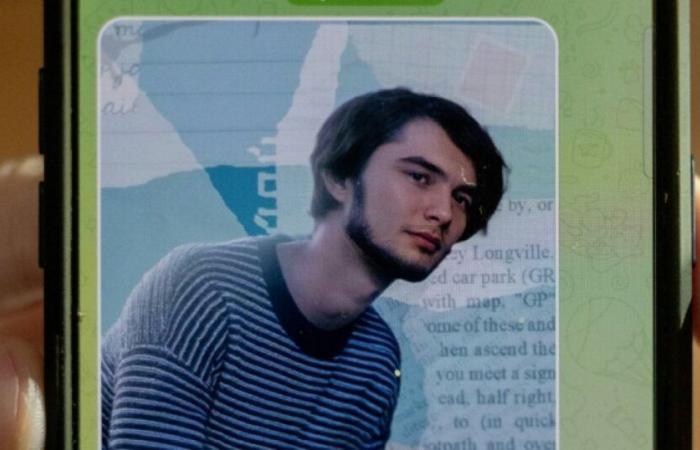

For a long time, she was unable to find a photo of Daniil Kliouka. She finally found one, taken on the fly during a class.

In this photo, dressed in a striped sweater, with a thin body, his thick black hair pulled back over his forehead, he is holding a wooden mannequin used to learn to draw. It looks like he's smiling.

For Sergei Davidis, head of Memorial's political prisoner assistance program, his treatment is not surprising. The secrecy of the affair allows the accused to be muzzled and the extent of the repressions to remain unclear.

Regarding the alleged denunciation of his superior: “The school is a conservative sphere where particular attention is paid to ideological loyalty,” observes Mr. Davidis.

“His denunciation was the opportunity to launch these legal proceedings, but people like him are also prosecuted without denunciation everywhere in Russia,” he underlines.

– Unknown prisoners –

Due to lack of access to the file, Memorial has not yet been able to add Daniil Kliouka to its list of political prisoners, which includes around 778 names, the tip of the iceberg.

Because, according to Memorial, the affairs of at least 10,000 people detained by Russia show signs of political motivation.

This includes, according to the kyiv-based NGO Center for Civil Liberties, some 7,000 Ukrainian civilians, such as journalist Victoria Rochtchina who died in prison on September 19, 2024.

The Russian organization OVD-Info has identified at least 1,300 prisoners for political reasons, to which must be added hundreds or even thousands of cases for “high treason”, “sabotage” or refusal to fight in Ukraine.

NGOs regularly discover prisoners thanks to reports from other prisoners. Daniil Kliouka thus informed Antonina Polichtchouk of his meeting, during a transfer, with Alexeï Sivokhine, a former Ukrainian soldier.

“He had been imprisoned for two years, alone in a cell, without any contact. Without Daniil, his case would have remained unknown,” notes Ms Polichtchouk.

Regarding informers, she wants to identify as many as possible, in the hope that they will be brought to justice “when this regime collapses”. An aspiration that could remain in vain: denunciation, massive under the USSR, was never discouraged or punished after the collapse of the Soviet empire.

– “Close your eyes” –

Antonina Polichtchouk slipped questions from AFP into a letter sent to Daniil Kliouka.

A week later, she received a response — as always, a handwritten letter sent by scan, dated and numbered — which fortunately had not been censored by the administration of Matrosskaya Tishina prison in Moscow, where he is in preventive detention.

Lately, entire sections of his responses have been crossed out with black pen. But not this time.

In his fine handwriting, difficult to decipher and similar to that which can be read on the letters published by his support group, Daniil Kliouka notes that the person who denounced him has two brothers who are fighting in Ukraine: “We can understand what's on her mind.”

As for the state of Russia: “Nothing changes in the country. It's a new development of the same situation (…) A ball rolling down a mountain, a car that no longer has brakes.”

He also talks about his love for drawing which allows him to “see things that never existed”.

The day after receipt of this letter, October 3, 2024, Daniil Kliouka was sentenced on appeal to 20 years of imprisonment to be served in “severe regime”, that is to say in particularly strict conditions of detention.

Each year, he will only be allowed one visit and one package.

He now awaits transfer to the prison industry's pipelines. To which camp? We don't know. The transport of detainees is carried out in secret. The journey by train can last weeks.

At the end of his letter, he believes that the part of society opposed to the Kremlin to which he belongs is “hunted and hated” because most of his compatriots have “closed their eyes and never open them again”.

“If the world hears this message, I ask them not to turn a blind eye.”

After this sentence, Daniil Kliouka resumes his epistolary conversation with his friend Antonina, as if nothing had happened. He asks her why she chose her profession. Then he tells her he has to go and kisses her.