If Charlie Hebdo journalists still demonstrate their desire to defend freedom of expression and their use of humor to this end, their working conditions have been affected since the attacks of January 7, 2015. The editorial team is now working in secret premises, under close police protection.

“No, they did not kill Charlie Hebdo.” The editor-in-chief of the satirical newspaper, Gérard Biard, is categorical at the microphone of France Culture: despite the attacks of January 7, 2015, ten years later, “Charlie Hebdo is still alive. Charlie Hebdo is still there. Including the cartoonists and editors , and our friends, whom they killed that day.”

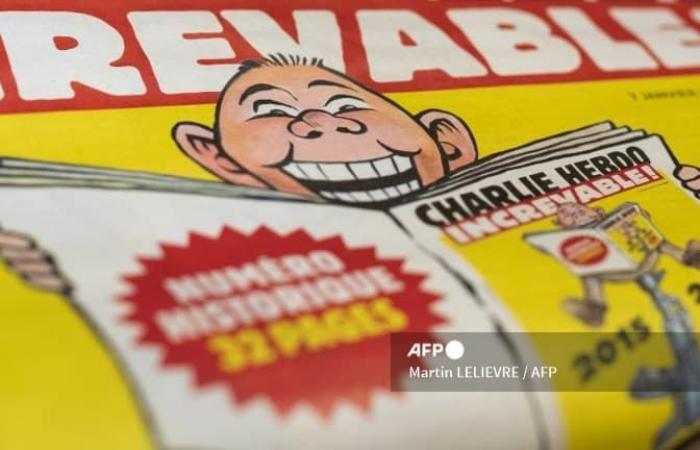

In the special issue, published this Tuesday, Riss, the publishing director, affirms that “the desire to laugh will never disappear”. On the front page, a reader seated on an assault rifle reads, delighted, this 32-page “historical” Charlie which includes four pages of caricatures of God sent by cartoonists from around the world. The satirical newspaper calls itself “incredible!”

“I don’t want to deny myself freedom.”

Several young journalists have joined the newspaper since the attack committed by the Kouachi brothers which left twelve dead, including eight members of the editorial staff. Among them, Lorraine Redaud, who assures on the microphone of BFMTV that if this “company has a heavy history”, it “manages to move forward”.

“When we arrive at Charlie, it's true that we have a bit of this fear that there will be a demarcation between the survivors and the newcomers. And in fact, as soon as we walk through the door we realize that “There’s nothing like that at all,” she adds.

One of Charlie Hebdo's young cartoonists, who calls himself Juin, joined the editorial team only three months after the attacks “to participate in the rebirth of the newspaper,” he explains to BFMTV. He assures that he is not afraid.

“My loved ones are worried, we don't talk about it too much but I know it can be complicated for them. They know that it's important for me to live this life 100%, I don't worry anymore questions than that,” says Juin. “I don’t want to stop myself from being free,” he adds.

Police surveillance, armored room…

A freedom, however, that has undeniably been encroached upon for ten years. The editorial staff and journalists live under close police surveillance.

70 to 80 police officers are permanently assigned to protect the premises, which are now kept secret. Only a handful of people know the newspaper's new address. To access the editorial office, you have to go through special doors, elevators and ultra-secure airlocks. No windows face the outside, a code name has been defined in the event of danger and an armored room exists to take refuge in the event of an attack.

“The level of security that has been adopted is that of an embassy in a sensitive environment,” says Frédéric Aureal, former head of the National Police Protection Service (SDLP), on BFMTV.

He explains that a “certain number of processes” are reserved “for the most threatened personnel” such as security officers, the installation of armored vehicles, “and a whole series of protections on which” he does not want “too much. expand.”

“The first time I arrived, I remember pushing several armored doors, and Riss saying to me ‘welcome to Société Générale’,” recalls Juin.

“We’re in a room where there aren’t really any windows. I swore to myself that I would never work under neon lights, and I work under neon lights,” he jokes.

“A bunker”

Coline Renault, one of Charlie's new writers, compares the editorial team to a “bunker” in the columns of the Journal de Québec. “There is no problem to say if we are afraid, if we do not want to participate in an event outside of the newspaper, if we do not want to have our photo,” she notes.

Before adding: “We were offered several times to sign under a pseudonym. They are very respectful of everyone's fears and feelings. But for me, it was not a question, because the locals are still very well protected.

The editor-in-chief, Gérard Biard, believes that this protection allows them to produce this newspaper as they “must do it”.

“That is to say with a certain lightness, by messing around, by arguing sometimes, but we must not be obsessed by something that parasitizes us,” he declares on France Bleu.

The most threatened journalists have also seen their private lives disrupted. “Daily life is no longer the same at all, we can't improvise, we can't say to ourselves 'the weather is nice', I'm going to go buy bread, we have to sort of plan everything,” Gérard Biard tells us .

But for him, above all, “what must be questioned” is the fact that a “satirical newspaper”, a “political newspaper”, must “be placed under protection in order to be able to operate”.