Twice a month, our journalist answers readers’ questions about health and well-being.

Published at 9:00 a.m.

I am 73 years old and I like walking. On the other hand, my husband and I do not have the same cardio-respiratory capacity. And that is my concern. How do we know when our maximum has been reached? When should you slow down so as not to risk a heart attack? I learned again this year of a man who died on a golf course in Punta Cana.

Diane Ouimet, Gatineau

Whether on a golf course in the Dominican Republic, in front of a snow bank or on the course of a marathon, when a person dies during intense effort, it captures the imagination. And it’s scary.

Is physical activity dangerous for the heart?

“It’s a question I get asked regularly,” says Dr.r François Simard, cardiologist at the Montreal Heart Institute. Although it is small, this risk exists, agrees the Dr Simard, “especially if the effort is acute, rapid, without preparation, without warming up”.

He gives a current example: snowfall. The aftermath of the storm, hospitals recorded an increase in the number of hospitalizations for heart attacks. But for the entire population who has to shovel on these days, “the rate of events remains low”, nuance the Dr Simard.

This is also the key message of the American Heart Association (AHA). The risk of dying from sudden cardiac arrest during physical exertion is “very low”: around 1 in 1 million.

PHOTO FRANÇOIS ROY, THE PRESS

The Dr Francois Simard

We are more likely to have heart problems not linked to exercise, therefore linked to our risk factors and our genetic conditions.

The Dr Francois Simard

It is a well-demonstrated fact: active people are, on the contrary, less at risk of suffering from cardiovascular problems. At the EPIC Center, affiliated with the Montreal Heart Institute, we train patients who have had a cardiac accident, to rehabilitate them, but also to reduce their risk of having a second one.

“People should especially focus on the benefits and pleasure they get from physical activity, but on the other hand, you have to go gradually,” explains Dr.r Simard, “that is to say, do not start at a high intensity when you are not trained”. He advises warming up well, hydrating well, and staying on the lookout for unusual symptoms during exercise: palpitations, chest pain, dizziness. It’s best to stop then, he says, and seek medical advice before starting again, to make sure there are no underlying problems. “Sometimes the first signs of a risk are very subtle,” emphasizes Dr.r Simard.

-Smoking, high blood pressure, cholesterol, obesity, diabetes and a sedentary lifestyle are all risk factors for coronary heart disease. Age too. After 35, 40 years, the risk begins to increase more markedly, indicates the Dr Simard.

What is the maximum?

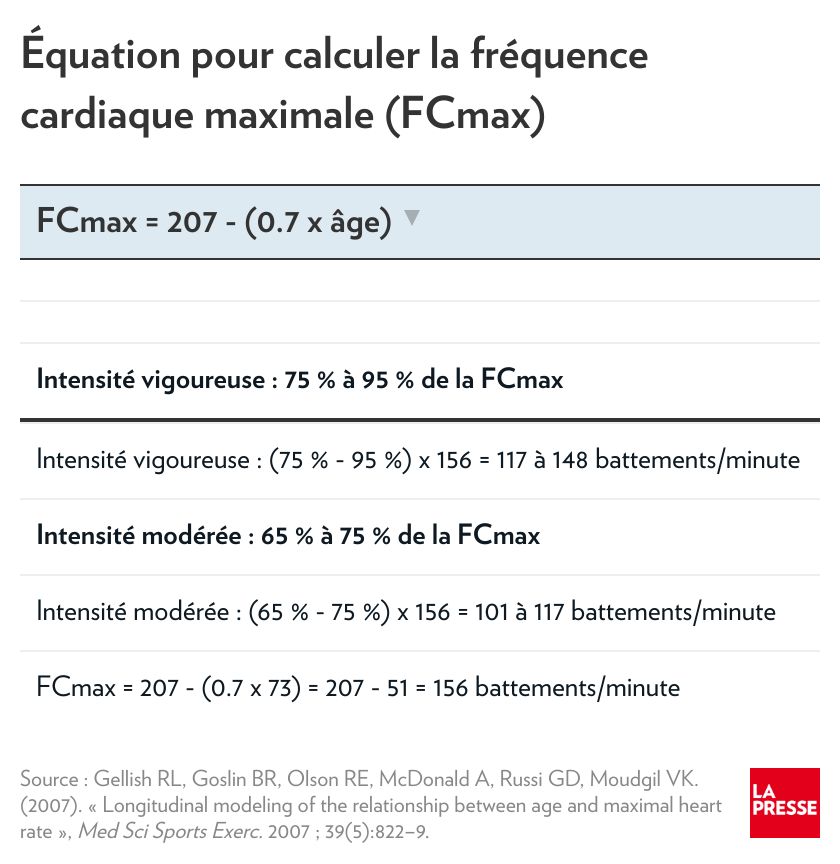

Our reader Diane Ouimet wonders how to know that you have reached your “maximum”. Can we trust the formula of “220 minus age”? she asks herself. This equation has been used for many decades to estimate one’s maximum heart rate (HRmax), or the number of beats one’s heart can handle, per minute, during exercise.

To know your true HRmax, you need to do an exercise electrocardiogram (the famous treadmill test), indicates Sophie Tanguay, kinesiologist at the EPIC Center. That said, there are indeed formulas to approximate it based on your age, including this one, which is a little more precise than the one which consists of subtracting your age from the number 220.

Monitoring your heart rate can be interesting for patients who want more, but what is important is how the patient feels.

Sophie Tanguay, kinesiologist

His recommendation, to measure the intensity of an effort, is “to really trust your feelings”. For physical activity to be beneficial, there is no need to make yourself completely out of breath: the intensity should be moderate (you can talk, but not sing) or vigorous (you have to catch your breath after a few words).

As heart problems are mainly associated with vigorous efforts, can we limit ourselves to moderate exercises? “Yes, absolutely. It’s about doing it longer, or more regularly, and we will obtain the same benefits,” replies cardiologist François Simard, who also does not advise against intense effort when the progression is adequate. At the EPIC Center, patients who have recovered well from a heart attack train at high intensity, with the approval of doctors, emphasizes Sophie Tanguay.

Because they are physiologically impossible to maintain for a long time, high-intensity exercises are done in the form of intervals, the duration of which can vary from 15 seconds to 4 minutes, depending on the protocols, indicates Sophie Tanguay. To have a plan adapted to your situation, the best, she says, is to consult a kinesiologist.

Should you seek medical advice before doing moderate or vigorous exercise? The American College of Sports Medicine has developed a model to guide people, available in Figure 2 of this statement.

View the statement

And among great athletes?

People who are in good shape can also be overcome by discomfort during a sporting event. It’s rare, but it happens. Do they have heart defects or unknown genetic diseases? “A portion, yes, but the biggest risk is heart attack, coronary heart disease, cholesterol which is deposited in the arteries,” explains cardiologist François Simard. The heart is stressed, a small cholesterol plaque ruptures and a clot forms, he summarizes. One hypothesis is that dehydration could contribute to the formation of clots, says Dr.r Simard. Again, people who have trained little before the event are more at risk than others.

Veteran athletes, who have been practicing high intensity at high revs for a long time, are more affected by atrial fibrillation, a heart rhythm disorder. According to one hypothesis, it is possibly due to a succession of microtraumas, accumulated over the years. “For the moment, we are treating them, but we are not stopping them from doing their physical activities,” says the Dr Simard. The risk still remains too low, but we observe it. »

Learn more

-

- 150 minutes

- The World Health Organization recommends a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity, or 75 minutes of vigorous activity, per week.