Houari Boumediene’s coup d’état in 1962 marked the establishment of what Algerians still refer to today as the “System”: a military-political structure that is both opaque and authoritarian, where the army arrogates absolute control over the workings of the State and the economic resources of the country.

In his “Filmed Memories” (1), Mohammed Harbi —former member of the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA) and negotiator of the Évian Accords, imprisoned by Boumediene from 1965 to 1971 before escaping and finding refuge in France—looks back at the key moments of this takeover. This began when Boumediene engaged in open conflict, in 1956, with the civilian and legitimate political class of the Algerian provisional government (GPRA): “One of the main demands of the general staff, namely Boumediene, was addressed to the GPRA: it was to put the wilayas under the dependence of the general staff.»

These six wilayas, placed under the direct authority of the GPRA, constituted autonomous administrative zones of the FLN. Each of them had a secret army and led the real war on Algerian territory. It was they who, by forming the National Liberation Army (ALN), won independence after a fierce fight from 1954 to 1962. Boumediene, however, wanted to replace them with the border army which he led and whose the officers had never borne arms against France: “The GPRA could not accept this proposal. If he accepted it, he lost his power base.»

The GPRA’s slogan for post-Independence: primacy of politics over military

Threatened, the GPRA organized an offensive in August 1956 to pull the rug out from under the army led by Boumediene. We are six years before the independence of Algeria: “The GPRA and FLN groups, supporters of Krim Belkacem, but actually led by Abane Ramdane, took over» in Algeria, and have “organized the Soummam Congress to adopt two principles in its program: 1) the primacy of the interior over the exterior; 2) the primacy of politics over the military.”

The primacy of politics over the military, coupled with a preference for the internal national army, “gave legitimacy to the elite bloc that Abane had created around the inner core of the military forces“. It effectively relegated the chief of staff Houari Boumediene, and the border army, to the dustbin of History and to a later secondary role in Algeria.

This democratic orientation, which opted for a civil government, with a socialist tendency, for liberation from colonialism, will officially prevail until independence in 1962, but it masks the rivalries that emerged in broad daylight between the “camp” of officers of the borders of Boumediene who favor a military regime and that of the GPRA politicians who want to place the army under the supervision of politics. With the blessing of the provisional government, the armies from the wilayas will claim their central role in the armed struggle and seek increased legitimacy.

Towards Independence: “Long live the GPRA! Long live Ferhat Abbes!» proclaimed the Algerian streets

Mohammed Habli describes an Algeria which resolutely took a stand in 1960 for the GPRA and its president Ferhat Abbes: “In December 1960, people came out in their thousands into the streets to shout: long live the GPRA, long live Ferhat Abbes. It was a decisive moment for the evolution of the Algerian question“. Until then, says the former provisional government executive, “Algeria was moving towards a rule of law» and independence «without political succession crisis».

The GPRA was approached the following year by De Gaulle to prepare secret negotiations which would lead to the Evian agreements. These agreements provided for a referendum on the independence of Algeria which was organized on July 1, 1962, leading to independence which was proclaimed on July 5. All this time, Boumediene has been kept out of negotiations with France and he is simmering his revenge, which will be cruel, and will fall on all Algerians accused of supporting the wrong side.

At independence, the temporary civil power of the GPRA returned triumphantly to Algiers on July 6, some from France, some from Tunisia, some from Morocco: “We returned just after the referendum, the entire government and cabinets returned on planes“, but the concern was palpable, specifies the former Evian executive and negotiator: “The GPRA’s concern was to organize things upstream, before the catastrophe (coup d’état, Editor’s note)“. The president of the GPRA, Benyoucef Benkhedda, who replaced Ferhat Abbes in 1961, feared the reaction of Boumediene, who was rumored to want to carry out a “redress of the Revolution”: “Especially since there was a rumor circulating, the FLN guys came to tell Azzedine (head of wilaya 4 including Algiers) that the casbah was mined, that they were going to blow it up. It was psychological warfare, and Azzedine finally gave in. There were a lot of things that weren’t clear.»

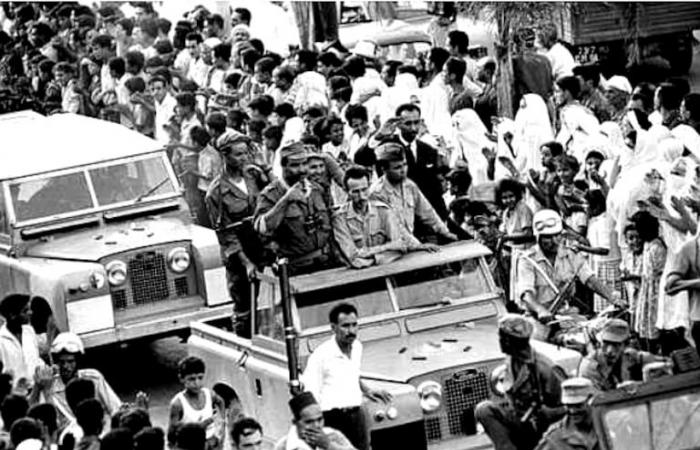

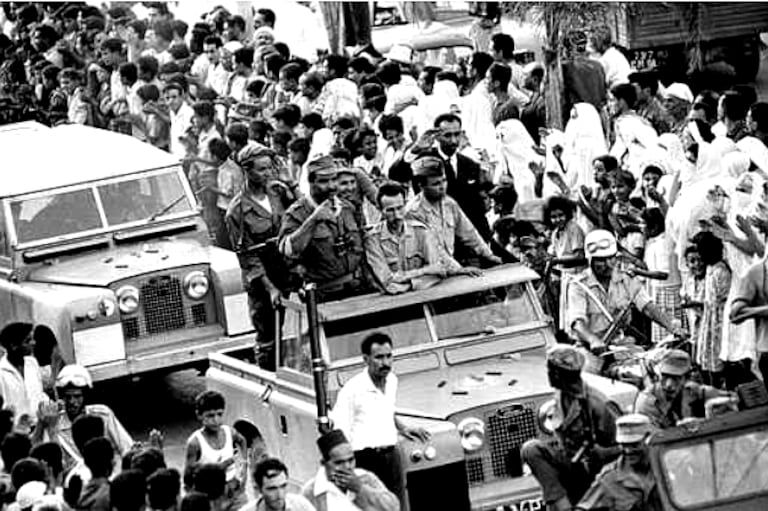

Colonel Houari Boumediene, who continues his march towards Algiers at the head of the National Liberation Army (ALN), crosses the town of Blida, on September 9, 1962, surrounded by colonels Ahmed Bencherif (to his right) and Mohamed Chaâbani (to left of Boumediene, commander of the 4th military region). After two months of power struggles and bloody battles which followed the proclamation of independence, Ben Bella and the supporters of the FLN Political Bureau, supported by the border army commanded by Colonel Boumediene, carried out a coup. State and take power in Algeria. (Photo Fernand Parizot/AFP)

Cheers in Algiers as Boumediene launches his coup from the borders

The ideals of freedom and justice, carried by civilian figures, were quickly stifled by military ambitions. In Algiers, we dance, we party, we congratulate each other for three days. Benyoucef Benkhedda, the legitimate president of Algeria, visits the neighborhoods and happily joins the crowd. Then on the fourth day, he decrees the end of the festivities and the resumption of work. “The country must continue to turn“, he said over the loudspeakers. All Algerians listened to him. Everyone, women and men, got back to work. But that was without counting on Boumediene who will take by force, what he was incapable of conquering by democratic means in Algeria. The summer of 1962, marked by the euphoria of independence, was also the scene of a silent tragedy which would seal the destiny of nascent Algeria.

While the people celebrated the end of a century of colonization, the shadows of the border armies, commanded by Boumediene, stretched across the liberated territories. Parts of the rear bases established in Morocco and Tunisia, “these forces, heavily armed and disciplined, had never fought directly on Algerian soil during the war of independence“, said this direct witness to the events. Their entry was “brutal“. Under the guise of restoring order, they advanced on the country’s major cities—Constantine, Oran and Algiers—like an implacable tide. Columns of armored vehicles and trucks carrying men in khaki uniforms swept through these urban bastions still marked by the scars of the war against France. But it wasn’t peace they brought: it was fear and domination.

In Algiers, “the Casbah, the pulsating heart of the resistance, was surrounded“. Boumediene’s troops seized the “ministries and official buildings under gunpoint“. Machine guns mounted on jeeps patrolled the narrow streets, imposing a climate of terror.

In this post-Independence Algeria, the border armies did not come as liberators. They came as conquerors. Their violence was not limited to bullets and bayonets; it was also exercised through propaganda, veiled threats and bringing opponents into line. Houari Boumediene, as project manager, imposed an iron regime which transformed the revolutionary ideal into a military dictatorship. This was the founding act of the “System” where weapons take precedence over ballot boxes. A sort of bastard democracy. Boumediene’s rifles not only took the towns; they took the hope of a people hostage.

The dissolution of the GPRA by Boumediene

For Boumediene, Algeria’s new strongman, who took power thanks to a coup d’état carried out in the tumult of independence, it was a question of “first of a brutal repression, and then the decapitation of the main revolutionary movement».

The historic president of the GPRA, Benyoucef Benkhedda, is ordered to cede the presidency to Ahmed ben Bella supported by the border army. He withdraws from power for the benefit of the latter to avoid “a fratricidal bloodbath», said Benkhedda. On July 22, 17 days after the proclamation of independence, Ben Bella established a provisional political office, which he directed, and declared himself in charge of state affairs.

This political office is actually led by Boumediene: “This political office of Ahmed ben Bella was created by a coup, it was supported by the general staff. The military staff decreed that they had the power, but they did not know, in truth, the power was elsewhere, in the hands of Houari Boumediene“. From then on, the political office will “eliminate all those who had not taken a stand for him, like me personally“, explains Mohammed Harbi in his memoirs, and “many people were definitively eliminated, GPRA ministers, President Benkhedda».

Boumediene, although acclaimed for his revolutionary rhetoric, was the tragic architect of a repressive state. Under his rule, civil liberties were sacrificed.

The origins of the “System”

The “System”, born from Boumediene’s military ambitions, has kept Algeria in an impasse ever since. The omnipresent army controls not only politics, but also the economy and institutions. Popular revolts, like those of Hirak in 2019, are a reminder of Algerians’ persistent aspiration for true democracy. Yet every attempt at reform comes up against the same reality: a deeply rooted military caste, ready to do anything to preserve its privileges.

Today’s Algeria is therefore the heir to this latent war between civil and military powers. The dreams of a democratic country promised at independence still seem out of reach. As long as the “System” does not fall, holding civil liberties and democratic aspirations hostage, the war between these two visions of Algeria will remain an open wound, preventing the country from recovering.

Notes:

1- “Mohammed Harbi, Filmed Memories”, 23 broadcasts, directed by Bernard Richard and Robi Morder, edition date: 2021.