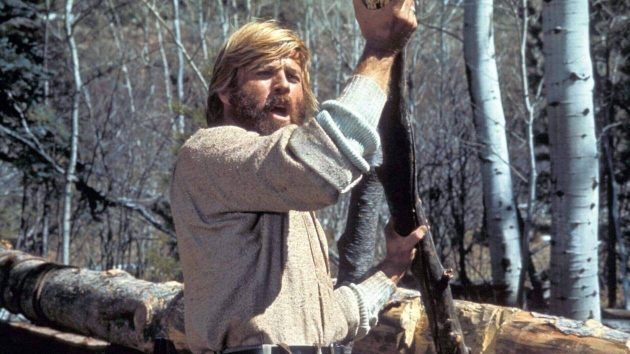

Who has never dreamed of eating raw liver wrapped in a bear skin in the high mountains? Forty years before Leonardo DiCaprio tried it in The RevenantRobert Redford tried the experiment in front of Sydney Pollack’s camera. This is the true story of Jeremiah Johnsontrapper amateur who terrorized the American Indians.

2012. Hurricane Sandy devastates the East Coast of the United States. A typhoon devastates the south of the Philippines… The Mayans told us: the world will stop turning on December 21st. It is in this pre-apocalyptic context that is spreading across social networks a contagiously viral meme. We see a man, dressed in clothes from another time, nodding his head. In the background a snowy forest can be seen. The good nature of the character associated with a particularly full beard misbehaves Internet users, convinced to identify Zach Galifianakis. So where does this come from? « nod of approval » ?

Seven years after surviving the end of the world, a certain Nick Martin identifies to his great surprise Robert Redford in Jeremiah Johnsonthe story ofa 19th-century Utah mountain trapper. Beyond the same decline in all sauces, this seminal film directed by Sydney Pollack notably nourished the genesis of The Revenant by Alejandro González Iñárritu. First western screened in competition at the Cannes Film Festival, Jeremiah Johnsona fictionalized biography of a human liver eater, paints in its meditative trappings the portrait of the end of a utopian world inevitably contaminated by violence.

The liver-eater who was zen

“In just a few years, the western has undergone considerable renewal. The order of its concerns has broadened to the point of no longer being the simple, constantly repeated exaltation of the conquest of the West, but rather an attempt at critical reconsideration of American civilization.notes Jean Gili in the review Movie theaterin 1971. While John Wayne pitifully perpetuates the myth of the Frontier, a gaggle of angry filmmakers dynamite this same moribund legend in a great cloud of powder when America turns the page on the 60s.

One of them, John Miliusdefector from the Roger Corman school, received an order at the time to adapt a biographical book recently acquired by Warner Bros, Crow Killer: The Saga of Liver-Eating Johnson. Its authors, Raymond W. Thorp Jr. and Robert Bunker, retrace the incredible destiny of John Johnson, known as “the Crow Killer », soldier converted into trapper in the Rockies in the mid-19th century. At war against the Crows who murdered his wife, a Native American, the mountain man lonely devoted twenty years of his life to bloody vengeance. Legend has it that he practiced it in particular in devouring the livers of its victims.

A ready-made story for John Milius, therefore, Self-proclaimed “Zen anarchist” with a passion for warrior culture and virile characters dilapidated against the elements as found in his favorite authors (Herman Melville, Joseph Conrard, Ernest Hemingway). This adds to the biographical material of Raymond W. Thorp Jr. and Robert Bunker a novel by Vardis Fisher, Mountain Manfree adaptation of Johnson’s vendetta.

A first version of the project was born under the leadership of “Bloody” Sam Peckinpah with Clint Eastwood headlining. Following them, Robert Redford takes a close interest in « the authentic mountain man story, based on well-documented real events, and closer to the real Wild West »reports Michael Feeney Collan in a biography of the actor, attached to “authenticity”to wild nature and particularly in the Rockies, where he made his home.

Son vois et ami, Sydney Pollackwho previously directed him in Prohibited propertyis easily convinced to adapt this “elegant literary work about a Paul Bunyan type [l’archétype du bûcheron dans le folklore américain, ndlr] »distant cousin of trapper Joe Bass, main character of son premier western, The Scalp Huntersreleased in 1968. Rewritten by Edward Anhalt, screenwriter of Panic in the street of Elia Kazan and The Boston Strangler by Richard Fleischer, nourished by notes from the director, it becomes and survival movie existentialist and melancholic.

Live and let live

“You don’t ‘play’ a movie like Jeremiah Johnson. It becomes an experience to which we must adapt […] We recreated a way of life that real people lived in these real mountains that are the same today as they were back then.”explains Robert Redford. Supported by Duke Callaghan, director of photography for Scalp Hunters which we will find in the credits of Conan by John Milius, Sydney Pollack, himself aided by a keen sense of decor, frames in Panavision the dazzling rugged landscapes of Utah in the style of 19th century romantic painters.

“The notes in my script all had references to old paintings by Bierstadt, Turner, all these mountain paintings which were very telling in a sense”claims the filmmaker in the film’s DVD commentary. A fresco tinged with lyricism, but also a meditative learning story. Laconic – the dialogues are reduced to the bone, Jeremiah Johnson tames this wild nature through chance encounters which sometimes take the initiatory towards the picaresque.

Moreover, we hardly know much about the past life of this mountain man melancholy. “He would have been a sailor, first on a whaling ship then in the US Navy, and may have been a gold prospector before becoming a mountain man […] He would have participated in two wars, the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) and the Civil War (1861-1865)”Thorp Jr. and Bunker argue in their book. The military attire worn by Robert Redford at the start of the film (jacket, cap, pants, boots and badge) subtly hints at this previous life which he will trade for the bearskin made by his wife Swan (Delle Bolton).

The storyline is more interested in violence lurking in nature, nestled in the depths of the human soul, without any Manichaeism. “Jeremiah Johnson walks through an Indian cemetery [un outrage dans la culture des Crows, ndlr] and he loses his family [assassinée en guise de représailles, ndlr]. He may be a legend, but he no longer has a place to sleep. Violence has enormous consequences »explains Milius in an interview with Creative Screenwriting Magazinein 2015. In the first drop of blood shed it is diluted the impossible ideal of an alternative lifestyle to the great outdoorsa proto-hippie utopia on its last legs at the end of Jeremiah Johnson.

The call of the forest

De Butch Cassidy (Butch Cassidy and the Kidby George Roy Hill) to Will Penny (Will Penny, the lonerby Tom Gries), via Monte Walsh (Monte Walshthe William A. Fraker), THE outsiders of the West colonize the screens in America in the early 1970s. These characters, reclusive on the fringes ofa society that has spit them out or doesn’t suit themoffer American spectators a specular image of a country in crisis.

“Looking at today’s reality is like looking through a glass »confirms Sydney Pollack in an interview with Michel Ciment and Natasha Arnoldi for Positivein October 1972. “Looking at the past is like looking through a prism; you always talk about white light, but you can make all kinds of parables with blues, reds and yellows…”.

Making his way through the mountains “in order to forget all the problems he knew”according to the eponymous song composed by John Rubinstein and Tim McIntire, Jeremiah Johnson anticipates by several decades the migratory ride of « back-to-the-landers »city dwellers who, tired or exhausted by urban life, return to the landinspired by “the idea of self-sufficiency in the wilderness that the trapper embodies”explicit Edward Buscombe in The BFI Companion to the Western.

Ce fantasy of an authentic existence intrinsically correlated with an idealization of the Border takes root in the writings of Henry David Thoreau who experimented with self-sufficiency in the forest several kilometers from his hometown, from 1845 to 1847.

“There is an American tension and dynamic in these two contradictory needs, that of solitude and a warm society. Huge cities follow others. You leave them for a solitary peace; and when you feel alone, you return to the city »comments Sydney Pollack in Positive. For good reason, the hippie movement shattered at the turn of the sixties when the last flames of the American socio-cultural revolution crackle. Violent police repression, economic recession et the decline of activism contribute greatly to its shortness of breath when they do not annihilate it.

Knowing he is threatened, Jeremiah Johnsonghost among ghosts, planning to go to Canada (“I have heard that there are lands that no man has seen”), refuge for young Americans from conscription during the Vietnam War. Unsuitable for modernity who pursues him, he disappears in a final dissolve that imprisons him forever in icelike the first trapper crossed on his route, thus completing the circular movement of the film.

One hundred and fifty years later, the “super-vagabond” Christopher McCandless, nourished by his reading of Thoreau, will encounter the same scathing failure after having also answered the call of the forest. A tragic odyssey from which Sean Penn will make a film with Emile Hirsch, Into the wildin 2007.