France CULTURE – ON DEMAND – PODCAST

“It is the story of those last words scribbled in haste before the silence and nothingness, thrown through the skylight of a cattle car, of a death train, left in the barracks of a camp, of a place of regroupment or internment, given in the haste and confusion of roundups and arrests to an unknown person, to a police officer, to a railway worker, to a postman, to a visitor from the Red Cross or to a simple passerby. » And it is the story, oh so moving, of these last words which, after reaching their recipients, after having passed through time, have now reached more official places of memory, that Alain Lewkowicz tells.

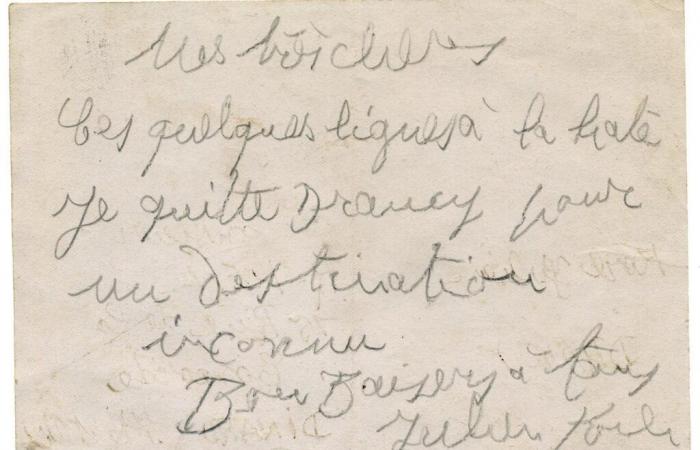

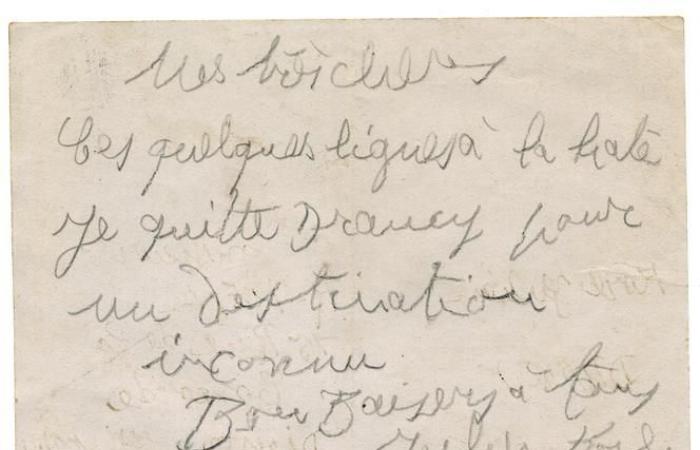

Granddaughter of deportees, a woman, a volunteer at the Shoah Memorial, says that she brought several documents there: a ration card, some photos, papers showing how the French government, during the war and until in 1945, sought out his grandparents to strip them of their French nationality “for one and only reason: because they were Jews”, and, dated April 24, 1945, a postcard from his aunt, who died of typhus in the Bergen-Belsen camp. “This card is the last link”she said.

“Connection with ghosts”

For Karen Taieb, head of the Shoah Memorial archives, “the last letter is the last trace of life. A proof of the existence of a person and something that was written by his hand: it is therefore an even more moving document”. These words were written on a piece of paper, on the cover of a book, on an advertising leaflet, on a metro ticket, on a business card, in short on what remained after the search. “These words are traces, and the need to tell loved ones where they are, where they are going and what is happening”says historian Tal Bruttmann. Most of the time thrown from the wagons, some – but how many?, asks the specialist in the Shoah and anti-Semitism in the 20th centurye century − never arrived at their destination.

-Heartbreaking are the words of this man, born in 1960, who tells the story of this postcard sent for Shana Tova, the Jewish New Year, by two of his father's brothers, from Drancy (Seine-Saint-Denis): “To our dear parents, may the year that comes comfort our suffering hearts by uniting each family once again under its roof. Your sons, Armand and Jacques. » Deported to Auschwitz, Armand, 20 years old, and Jacques, 9 years old, will never return. “It's the only connection I have with the ghosts I've lived with since I was bornsaid the man. This is one of those documents that repairs fabric that has been torn. We are Schneiders, we repair [Schneider signifie tailleur, couturier, en allemand]. Our fabric, our world, has been torn apart, and each document is a little seam: we try to repair as best we can. »

For historian Annette Wieviorka, these words, as the last signs of life, are like relics. She herself has no letters from her paternal grandparents, who died in Auschwitz, only her grandfather's identity card and her mother's Jewish star. Karen Taieb hopes that more and more families will entrust these “last words” to the archives.

“The last word”, a program by Alain Lewkowicz, directed by Guillaume Baldy (Fr., 2025, 2 x 28 min). To be found on France Culture and on all the usual listening platforms