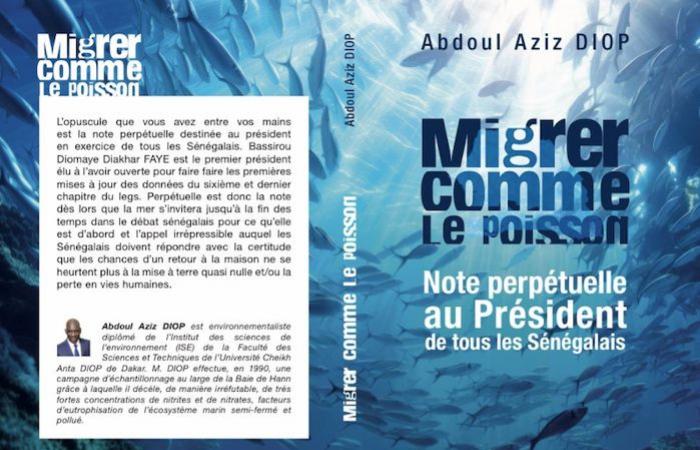

Twenty-two years after its collection “We chose the Republic…”, Abdoul Aziz Diop returns with an ambitious political essay. Combining Machiavellian philosophy and contemporary issues, he offers a new reading of Senegal’s maritime challenges. His book “Migrate like the fish…” (L’Harmattan Senegal, January 2025)addressed to President Faye, draws the contours of a patriotism anchored in the sea. A profound reflection on the future of a country whose destiny is intimately linked to its maritime spaces. Below is the preface:

This book – instead of a long open letter – is a voluntary open note addressed first to the President of Senegal elected on March 24, 2024 in the first round of voting with 54.28% of the valid votes cast. Our conviction is that the meaning of our approach will be better understood following the reminder of a few key precepts taken from the The Prince by Nicolas Machiavelli (1469-1527). With said precepts must begin any dialogue at a distance or face-to-face with, at all times and in all places, the universal hero of the Italian philosopher. In short, readers will finally understand why advising Diomaye without him having asked for it – this is the case in this note – on fisheries and migrations with which they can be positively correlated.

Born in 1469 in Florence (Italy), Machiavelli wrote, from 1513, The Prince, which ensures the name of the philosopher its universal fame. “The book, [qui ne fut imprimé qu’en 1532, cinq ans après la mort de Nicolas Machiavel]was admired by Napoleon, Lenin, de Gaulle, but also Mussolini. » The novelist and essayist Jean Anglade – accredited in Italian -, maintains that “the scandal was that this little book dared to study, to expose in broad daylight, black and white, a way of being always carefully enveloped until then in hypocritical veils.”

Oscar Morgenstern, quoted by Raymond Aron in a preface to Prince“deplores that modern specialists in political science have not subjected Machiavelli’s precepts to rigorous analysis in order to identify those who, [aujourd’hui encore]retain (…) an operational value”.

The common trait of “Machiavellian” princes is rather the lack of Machiavellian virtue. This covers “the various physical and spiritual talents that nature can give to a man”. It “corresponds alternately or all together to intelligence, skill, energy, heroism”. It is undoubtedly this virtue which determines, more than anything else, the way in which a prince “must behave to acquire esteem”. First, a virtuous prince must “accomplish great undertakings and set rare and memorable examples of himself.” Secondly, he must “give outstanding examples of know-how in domestic problems”. Third, the virtuous prince must take “care (…) to preserve the majesty of his rank, which on no occasion should be tarnished.” Fourth, finally, he “must (…) show that he appreciates the various talents granting work and honors to those who are most distinguished in this or that art”.

-“(…) We can judge the brains of a lord just by seeing the people he surrounds himself with,” writes Nicolas Machiavelli. ” When [les ministres du prince]he writes, are competent and faithful, we can believe in his wisdom (…) but if they are the opposite, we can doubt what he himself is worth (…) » Some say that a sitting president is less faithful in friendship than the opponent he was. This is because “(…) he who causes the ascension of another ruins himself; To do this he could have used skill or force; but both will then be unbearable to him who has gained power.” “If men who appeared suspicious at the beginning of a prince’s reign need the prince’s support to maintain themselves, he will be able to very easily win them over to his cause. They will then serve him with all the more zeal as they will feel more duty-bound to erase the bad opinion he had of them at the beginning. » This last precept perhaps better explains the way in which we adapt to transhumance – recruitment of former adversaries – to consolidate a party. But the transhumants – the new recruits – would be careful not to talk to the president about anything other than the country if the latter knew how to “flee the flatterers” that they have all become. Machiavelli exhorts the “wise prince [à choisir] in the country a certain number of wise men to whom (…) he will allow him to express himself freely, (…) on the matters of his choice. “The prince who acts otherwise is lost by flatterers; people often change their minds, depending on who last spoke, which can hardly earn him any esteem. » “A prince who lacks wisdom will never be wisely advised,” maintains Machiavelli. “Good advice, wherever it comes from, always comes from the wisdom of the prince, and not the wisdom of the prince of these good advice”, writes the author of the “pamphlet on governments”, original title of the Prince. “A prince,” writes Machiavelli, “must (…) care little about being called a scoundrel, so as not to be inclined to plunder his subjects, to be able to defend himself, to avoid poverty and contempt, to not not be reduced to stratagems. »

“A Republic defended by its own citizens falls more difficult under the tyranny of one of its own (…)” For not having understood this, the radical wing of the OK – change in ouolof -, déliquescent would have brought mercenaries into the country under former president Abdoulaye Wade. But, “mercenaries,” warns Machiavelli, (…) are useless and dangerous, because if [le prince] based [son] State on the support of mercenary troops, [son] throne will always remain shaky. Yesterday as today, the mercenaries “agree to belong to the prince as long as peace lasts, but as soon as war comes, they only think of playing around.”

“The number of “Machiavellians” who have not read a single word of Nicolas Machiavelli certainly exceeds (…) that of the “Marxists” who have not read Karl Marx,” comments Jean Anglade. For having read Machiavelli, the Cameroonian essayist Blaise Alfred Ngando publishes the work Prince Mandela: An essay on a political introduction to the African Renaissance (Maisonneuve & Larose, 2005) “For Ngando, “Prince Mandela” and Machiavelli’s “Prince” would be driven by the same “essential value”: patriotism. » But not just any patriotism! That of Ngando cannot be summed up in a “project” that we call “systemic”, “holistic” or whatever. The patriotism in question here finds in our 198,000 km² of maritime spaces, the territorial continuity of the 196,720 km² on which are traced the paths, still insufficient, even insignificant, of our full collective development, the only one capable of us to definitively free ourselves from our dehumanizing dependence on others who are both so distant and so contemptuous. The patriotism which is finally in question here finds in the irrepressible call of the sea our objective reasons to accommodate the belligerence of the other in the winnable debate of the world with the irrepressible opinion – ours -, constitutive of our double Senegalese and African identity.

As its subtitle shows, this booklet is the perpetual note intended for the current president of all Senegalese people. President Bassirou Diomaye Diakhar Faye is the first to have it in his hands to take the advantage that the volunteer author has the right to expect from it. Perpetual is the note since the sea will invite itself until the end of time in the Senegalese-Senegalese debate, thus requiring irrevocable updates with each democratic alternation.