For Augatnaaq Eccles, sewing parkas is a way to get closer to Rankin Inlet, his community in Nunavut, while remaining in Ottawa. However, like many Inuit, the young woman is often forced to sell her works at prices much lower than their real value. A reality from which some art dealers take advantage.

Fortunately, changes to the Copyright Act, proposed in the federal government’s 2024 fall economic statement, could remedy the situation. The artists would then receive part of the proceeds from the resale of their works.

The Inuit artistic community has been impatiently awaiting this reform for several years now. More than 90 countries around the world have adopted a similar royalty system, including Australia, the United Kingdom and all member states of the European Union.

According to Ms. Eccles, these legislative changes would ensure greater fairness. Some artists sometimes receive not a cent from their works sold for thousands of dollars.

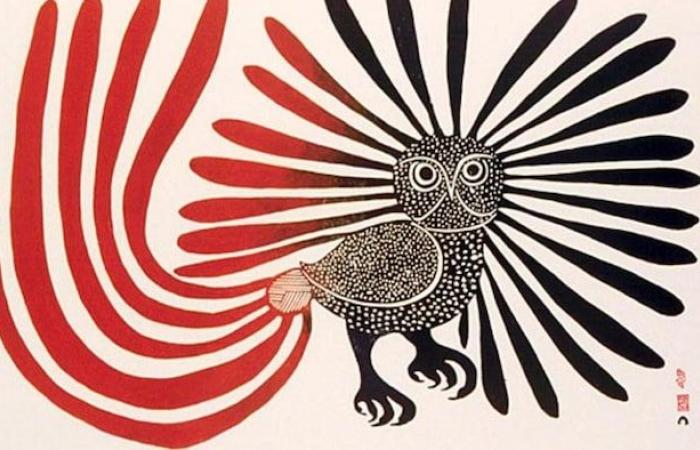

As an example, she mentions the famous owl of the eminent artist Kenojuak Ashevak, included in particular on the Google search engine on the occasion of her posthumous birthday.

When this emblematic work of Canadian culture was first published in 1960, the engraving was sold for the modest sum of $75. On December 2, a blue ink reproduction of the engraving sold for $366,000 at the auction house First Arts.

Open in full screen mode

The enchanted owl of Kenojuak Ashevak, a symbol of Indigenous art in Canada, has long appeared on Canadian stamps.

Photo : West Baffin Co-Operative Ltd.

Augatnaaq Eccles acknowledges that this is an extreme case, but the Inuk artist believes that regardless of the resale value, artists should always receive a portion of the proceeds.

In cases where the artist has died, the royalties should go to the estate, according to Ms. Eccles, as should be the case in this case with the auction of the reproduction of the enchanted owl.

Details of the proposed legislative amendments will be revealed when they are presented to Parliament, according to the Department of Canadian Heritage. No date is planned at this time.

Questions remain

According to William Huffman, executive director of the West Baffin Co-op, Canada’s oldest arts organization owned by an Indigenous group, the announced reform is a step in the right direction, but it comes with many unresolved issues.

Some of his concerns include how sales will be tracked, whether a minimum sales price will be required for a royalty to apply as well as the administration of payments to the estate of a deceased artist.

Communication with the artists concerned, who often reside in isolated regions, also raises concerns for him.

We already have difficulty working with our artists when it comes to distributing royalties, fees or even getting their permission to participate in certain things

he notes.

This is why it is fundamental, according to Mr. Huffman, that any federal agency responsible for regulating the future royalty system, if adopted, establishes local partnerships in regions where Inuit artists live.

Open in full screen mode

William Huffman (right) unboxes Inuit artwork at the English Harbor Arts Centre.

Photo: Courtesy of Valerie Howes

Augatnaaq Eccles suggests that artists have the possibility of contacting a designated person in each community, or that they be able to consult posters in public places.

Based on a text by Samuel Wat of CBC Indigenous.