Under Nazi Germany, many works of Art by Jewish collectors were stolen, confiscated or sold at low prices. In the Netherlands, hundreds of these works were returned by the Allies during the fall of 1945, but only a handful were returned to their owners or heirs. Until March 9, 2025, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is highlighting the story of one of these stolen paintings, Rest, peasant woman lying in the grass (1882) by Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), and the Van der Bergh family, who had to part with the work to escape the Shoah.

A restitution request that had not been processed

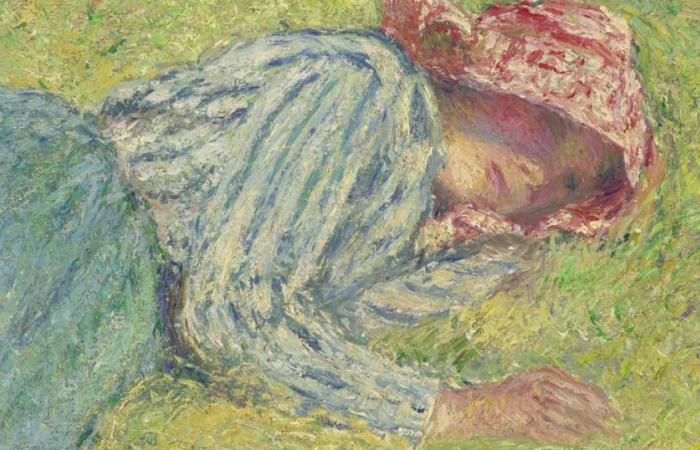

Rest, peasant woman lying in the grass is part of the series of rural figures that Pissarro immortalized between 1879 and 1882. It represents a young girl lying in a sunny countryside landscape. Pissarro captured the peaceful scene using light streaming across the grass. The flat background is reminiscent of Japanese prints which may have influenced the painter. Coming from a family of entrepreneurs from northern Brabant, Jaap van den Bergh acquired the painting shortly after Germany invaded the Netherlands. In 1943, Jaap and his wife Ellen van den Bergh were forced to sell the oil on canvas to go underground, like many other Jews needing money to flee the country, hide or obtain false immigration papers. identify. The couple managed to survive the war but their daughters Rosemarie and Frieda Marianne were murdered in Auschwitz.

Frieda Marianne and Rosemarie van den Bergh. ©Private collection

After the war, Jaap van den Bergh declared that the sale of his painting was made under duress, but his request for restitution was not processed. It was only in 2016 that the history of Resting, peasant woman lying in the grass resumes. A digitization project by the Origins Unknown Agency (a now defunct organization) recreates the link between the Van den Bergh family and the painting. Thanks to this document, researchers locate the work in the collection of the Kunsthalle Bremen and provide the missing link of its provenance. After researching potential descendants of Jaap van den Bergh, only a third sister of Rosemarie and Frieda Marianne, born after the war and unaware of the existence of the painting, was identified as the beneficiary.

Camille Pissarro, Le Repos, peasant woman lying in the grass, 1882, oil on canvas,

Kunsthalle de Brême ©Kunsthalle Bremen_Der Kunstverein

A fairly unique compensation agreement

Following this discovery, an arrangement between the Kunsthalle of Bremen, which has kept the oil on canvas since 1967, was reached with the heiress and the institution. Besides the financial compensation (the amount of which was not disclosed), the compensation agreement is quite unique. It includes a scientific study on the history of the Van den Bergh family during the years of German occupation, the publication of a work compiling the research, as well as a temporary exhibition in the Netherlands. It is within the framework of this agreement that the Van Gogh Museum welcomes the loan from the Kunsthalle Bremen.

The Art Gallery of Bremen in 2007 ©Wikimedia Commons/Jürgen Howaldt

Next February, the work Girl in the Grass, The Tragic Fate of the Van den Bergh Family and the Search for a Paintingwritten by Eelke Muller and Annelies Kool (experts on the issues of restitution of cultural property from the Second World War) with contributions from Dorothee Hansen (deputy director and curator at the Kunsthalle Bremen), Brigitte Reuter (researcher from the Kunsthalle Bremen) and the historian Rudi Ekkart, will be published by Waanders in English and Dutch. It will trace the family’s poignant story, from the search for the painting to the scars left by the war.

Finally, Rest, peasant woman lying in the grass will return to the Kunsthalle Bremen on April 3, 2025 with a new presentation including a contextualization of its provenance. While other institutions struggle to find an agreement with the rights holders of Jewish families dispossessed of their collections during the Shoah, the example of the Pissarro of the Kunsthalle gives a little hope by showing that a fair agreement for both parts is possible.

The Impressionist Revolution of Camille Pissarro