From this period of wonder, Michel Pastoureau also remembers a fanciful tribe, with independent women. “My family was ahead of the curve for a lot of things. From my grandmother’s generation, women were educated, and honesty forces me to say that it was they who wore the pants. When the events of May 68 emerged, I did not understand what the young people were demanding. In my family, all this had existed for at least two generations,” he laughs.

This taste for freedom remained with him, to the point of exploring subjects at the time “on the margins” and becoming a trailblazer in cultural history. While he will be in La Chaux-de-Fonds for two conferences on November 12 and 14, at Club 44 and the International Watch Museum, he talks about some stars from his galaxy.

The Luxembourg Gardens, the workshop for reflection

“It’s one of the great public gardens in Paris and because, for me, everything goes back to my childhood, I love this place. I’ve even been around him all my life. When I was little, I came there two to three times a week, with my grandmother, who lived right next door. I then attended a neighboring high school, before studying and then teaching at the Sorbonne, still nearby, which allowed me to return there.

For my part, I was a timid child from Luxembourg, who did not stray too far from his grandmother’s chair. When she became too old to move around, I practically replaced her, going to sit in her place for a long time. Later, I found a new place, more sheltered from the wind and prying eyes, and it is still there that I like to retreat to observe and reflect.

I am convinced that there are places where people think better than elsewhere, and I think extremely well of Luxembourg. Being neither reckless nor adventurous, I like meditation in domesticated nature. This is how I discovered that I also thought very well about the Lausanne campus, which is after all the most beautiful in Europe. But, like my youngest daughter who settled right next door, I have the idea that the Luxembourg Gardens are the center of the world.”

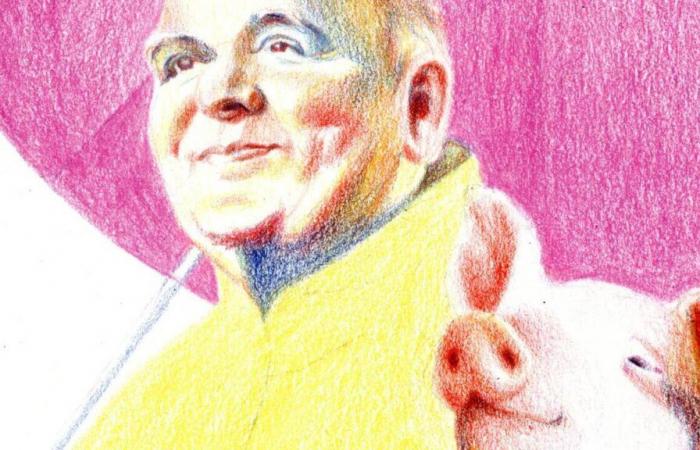

The pig, so close to us

“I have worked a lot on the history and symbolism of pigs, because I have an immoderate love for pigs. As a Sunday painter, I also drew them a lot. Over time, I realized that this love is quite widespread and is reflected, as in my case, by strategies of small collections of trinkets or precious objects in the shape of a pig.

Once again, my love goes back to childhood: my parents’ country house in Normandy had as a neighbor a farmer who raised extremely friendly free-range pigs. As soon as I approached them, they came to be petted, because the pig is very affectionate. It is also most interesting for the humanities, due to stories of attraction, rejection and taboo.

We also know from ancient Greek medicine that it is the animal closest to the human being biologically, which is why so many organs are borrowed from it for transplants. And I am convinced that taboos, in certain religions and societies, come from this relationship between man and pig. For certain societies, this proximity is too strong and to eat pork is in some way to be cannibalistic. For my part, I believe in the unity of the living world, and I don’t put so many boundaries between man and animal, but without being vegan.

Ulysse Nicolet, the precious Latinist

“The professor who had the most impact on me during my studies was specialized in the Latin theme, that is to say the transition from modern French to the Latin of Caesar, Cicero and others. He was from Savoy, a very good grammarian and just as good a teacher, and we all loved him very much. He taught me to appreciate the stylistic choices of ancient or medieval authors, with a true delight in language.

As a historian of the Middle Ages, almost all the documents I consult are in Latin. But I also do it for pleasure, switching from modern French to Latin, to translate all kinds of improbable things: user manuals for household appliances, rules of field hockey…

Having been married for fifty-six years, I probably also had to translate words of love to my wife, herself a Latinist. We met during our studies. We found ourselves sitting next to each other on the first day of the school year. She subsequently specialized in the history of cartography, before directing the library of the Institut de France. We also had the immense privilege of living in this place, which is the most beautiful palace in Paris.

I loved this period. And then I myself have a huge library of around 35,000 books. Today, I try to give them away, to save space, but no one wants them. Donating books has become difficult because of everything online, you have to leave them clandestinely at night, on the sidewalk, hoping that someone will come and take them. I’m a little ashamed.”

Gino Bartali, the sporting icon

“I am very interested in sport and the sportsman who had the most impact on me as a child was an Italian cyclist named Gino Bartali. He had his career before and after the war. Above all, he entered into a rivalry – a very famous story – with another Italian rider named Coppi. It is a social fact which has the value of a place of memory. And so, as a child, I played with little cyclists in the sandbox, with my friends who all had their own runners. Mine was always Bartali. Was it his name, his photo? I don’t know why I chose one over the other.

Subsequently, I learned that Bartali rather represented a certain Italy, traditional Catholic, with racing methods without doping, while Coppi represented modern Italy, with new training methods, and perhaps already a few performance-enhancing drugs.

My interest in sport remains intact, even if I have never been able to be enthusiastic about French athletes, because I am annoyed by the nationalist hysteria in sport. We saw this again recently during the Olympic Games: on the radio, we were always told where a particular Frenchman had finished, but without ever giving the result. I am not a fan but if I had to support a country, it would not be France, but rather Switzerland, which I am in love with. Almost everyone is in a good mood in Switzerland. Which is exceptional for a Frenchman.”

The rain, the melancholy attraction

“To dream well, I think it has to rain. I can still see myself in my mother’s pharmacy, as a child, watching through the glass door the late summer rains falling with a poetry that seemed to me the most beautiful spectacle. Even today, wherever I am, I love the autumn rains. I know it’s a shoddy romanticism, but everything that is of the order of melancholy attracts me enormously. October remains my favorite month.

In the Middle Ages, it was said that there were two autumns, with a first half which was the beautiful autumn in a way, and a second part entering the cold season. And we placed this break around November 11, which was also a very big celebration, Saint-Martin. It was the period when we moved from the outside to the inside, bringing in agricultural tools, livestock, children… I myself remain quite sensitive to this break.

I obviously like seeing the rain fall on the Luxembourg Gardens. I also like seeing it fall on Paris because it blurs the differences between the rich and the more modest neighborhoods, and it highlights many things, revealing the contrasts better when everything is wet. And I particularly appreciate the symphony of drops in attic houses, when the rain falls on the tiles or slates. It’s music with incredible charm. There would be a beautiful cultural history of rain to write, but I am still 77 years old now, and my schedule is full to the end.”

Course

Son of a father close to the surrealists and a mother who was a pharmacist and then a researcher at the CNRS, who studied at the Ecole nationale des chartes, where his thesis focused on the medieval heraldic bestiary, Michel Pastoureau became director of studies at the EHESS. He taught for a time at the universities of Geneva and Lausanne, and was entrusted with the role of historical advisor for films Perceval the Welsh by Eric Rohmer, and The Name of the Roseby Jean-Jacques Annaud. He has published around forty works and received numerous awards.

Michel Pastoureau in conference in La Chaux-de-Fonds