On the occasion of the exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, Lise Baron creates a sensitive portrait of the painter through his canvases. Gustave Caillebotte, discreet hero of impressionisma documentary to watch this Friday, November 1 at 10:55 p.m. on France 5.

His curse: having been rich. Because he was free from want, even more so than a Cézanne or a Morisot, Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894) has long been confined to the ranks of the second knives of Impressionism. Almost a Sunday painter with these boaters, these scenes of bourgeois life with onlookers and peaceful workers. At least he was saluted for his activity as a collector. Early in fact he had acquired works from his modern friends.

This commitment to Pissarro, Monet, Renoir and other Sisleys, all of whom, in their early days ate mad cows, as well as this role as unwavering promoter of their way of course justifies recognition. But this obscures the intrinsic value of the artist. The author of the Parquet planers a you Bridge of Europe remains mainly as a sailor and botanist. His passion for regattas was such that he established himself as a naval architect. And on earth Caillebotte was a magnificent gardener, even before Monet of Giverny or Clemenceau of Saint-Vincent-sur-Jard.

Dizzying prospects

Yachtsman and gentleman farmer certainly, but painter, then? On the occasion of the exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, Lise Baron searches for, and finds, the particular genius deposited in the works. His numerous zooms on the details and thicknesses of the paintings speak for themselves. This taste for canvas left visible here and there? It is perhaps the legacy of a father who supplied sheets for the army of Napoleon III. This propensity to magnify Haussmann’s Paris? Happy family investments made in real estate.

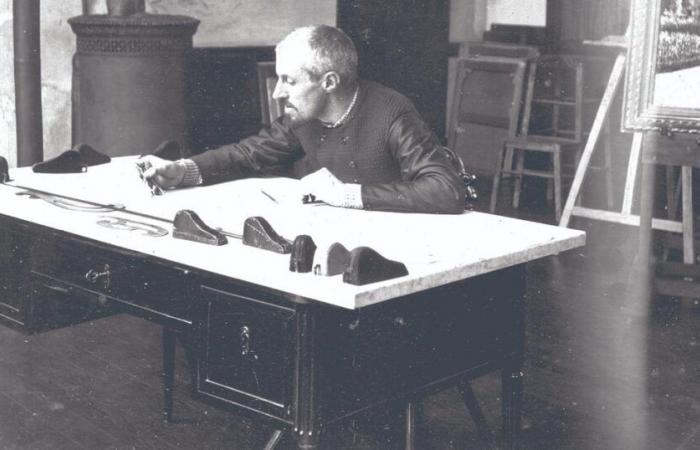

And then, if the exterior was discreet, as the rare self-portraits and photographs show, Caillebotte had audacity to spare. At least as much as his peers. His framing? They are inspired by Japanese prints appreciated from the 1870s. His perspectives? They turn out to be as new and even more dizzying than those of Degas. The touch, less apparent and radical than that of a Monet? It excels at making the pavement wet, the laundry billowing in a breeze or the sail cutting through the blue of a summer day.

Above all, even in his representations of flower beds, a melancholy emerges. It derives from that of the masters of the Dutch Golden Age and the musical art of Watteau. It is nourished by a close-knit family, forever bereaved by the early loss of the father, then that of a brother who left at the age of 26.

A diffuse splenic

The carefree adolescence between Parc Monceau and Saint-Lazare station was soon over. Already, from the top of the balconies of the Avenue de l’Opéra, there is nothing but gaping, empty space. Caillebotte certainly lived there in the best comfort, but also in diffuse spleen, his mind alienated in small things, a meal, reading a newspaper, embroidery. And even, on the boulevards side, he doesn’t seem to have allowed himself any other spectacle than that of the windows.

Near Yerres, Le Petit-Gennevilliers has taken over. It was another country retreat, equally silent. Caillebotte found a form of peace there, different however after the wars, the mourning, the upheavals and the trepidations of the new Paris.

We could still breathe in these suburbs. That is to say, paint there. The idea, in the air since Corot, is to capture light in its natural environment. And also, here as in Paris, to follow Baudelairian advice: the best way to make life eternal is to embrace the here and now.