In February, scientists studying children with sickle cell disease found that catastrophizing was the best predictor of whether pain would interfere with their daily activities four months later. How these children thought about their pain had more influence than other possible factors. “More than anxiety, depression, and even [une influence] on the pain state they were in initially,” says Mallory Schneider, co-author of the study and a psychologist in private practice in Roswell, Georgia. Additionally, last month, researchers reported that greater pain was significantly correlated with greater pain catastrophizing as well as more depressive symptoms in women with breast cancer-related pain.

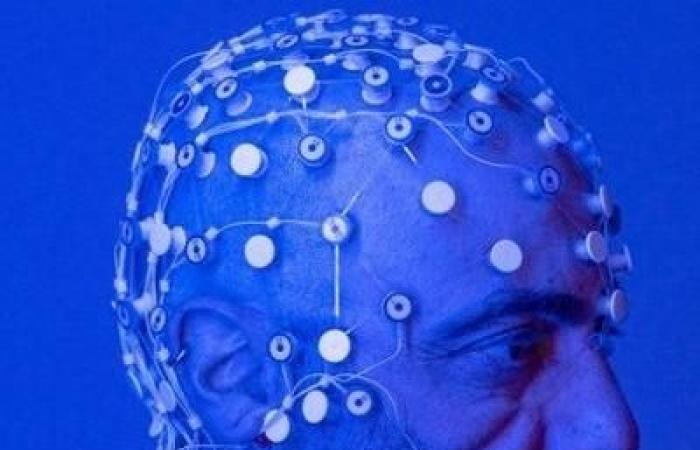

Although specialists do not yet understand the precise mechanisms at work, they do know that catastrophizing does influence the brain. Functional MRIs have made it possible to document these effects; Brain regions involved in pain perception and modulation light up when patients catastrophize.

The extreme mental activity that occurs when experiencing pain is a natural process that makes biological sense, says Eve Kennedy-Spaien. “Our brain is programmed to stay alert for danger and to review worst-case scenarios in order to protect us,” she explains. But in some cases, the alarm continues to sound long after a physical injury has healed. »

According to her, doctors sometimes exacerbate this catastrophizing by using intimidating medical jargon to describe an injury to a patient: we hear that the “bones are touching” to speak of arthritis or that a disc is “herniated” when the pain is not necessarily there; this can reinforce the impression that there is danger.

Mallory Schneider draws attention to the possible influence of racism at work in the health system: African-Americans are more likely to catastrophize than white people. “It’s been the case for a long time, we don’t take black people as seriously when it comes to assessing pain, and over time, this need to express it in a way strong enough to be taken seriously can become a way of adapting,” she explains.

According to Mark Lumley, a psychology professor at Wayne State University, pain specialists who know the importance of curbing their patients’ tendency to catastrophize usually redirect them to cognitive-behavioral therapy. . It is often used to treat depression, eating disorders and even post-traumatic stress disorder. But according to him, the scientific literature shows that this type of treatment is not really effective against pain. In 2019, a review of the literature on chronic musculoskeletal pain evaluated the combined effect of this therapy with physical exercise. Conclusion: This brings little or no benefit.

For a change, Mallory Schneider says, doctors could try spending more time talking with their patients about the frequency and severity of their pain episodes. Listening to children with sickle cell disease consistently describe their pain in extreme terms to her, she decided to start her own study. “They would say: ‘I’ve never felt so bad’ or ‘It never goes away’. But when I asked a few more questions, I got a more balanced perspective,” she says. The children became aware that their pain had already been more intense or that previous twinges had indeed disappeared.

Rather than simply asking patients to rate their pain on a scale of 1 to 10 as is usually done, Mallory Schneider urges doctors to take the question further. “This would help patients get a clearer picture of what they are experiencing, and it would help doctors, because otherwise they might become frustrated with the patient and thus fail to treat their pain properly.” , she comments.

She said it would also be beneficial to include screening for pain catastrophizing in routine paperwork. “Medical infrastructures are much better at detecting depression and anxiety than catastrophizing,” she says.

At Spaulding, teams of doctors, psychologists, physical therapists and other practitioners attempt to distract patients from the “danger messages” they send to themselves. These messages often focus on the risk of additional physical injury or extreme pain if they were to make a gesture that causes discomfort.

“We help people understand the difference between pain and injury,” advises Eve Kennedy-Spaien. Certain movements can trigger unpleasant sensations or even excruciating pain without any damage being done, she explains. According to her, it is particularly important to start performing these movements slowly, because “when someone completely avoids activities, it prevents the brain from recalibrating itself” and realizing that a particular movement is safe.

According to Spaulding patient Michael Cross, learning to reduce his negative messages has been a godsend. This 68-year-old retired contractor was seriously injured in 2019 when he fell onto a steel base near an outdoor garbage chute. Michael Cross has undergone ten major surgeries (and counting) to repair bone and nerve damage to his face and arm. Until last month, the pain consumed every waking minute and he feared he would never be able to get rid of it.

Because of the damage to his nerves, he feels like “bees [le] stings all the time,” but the change in the signals his brain sends gives him hope for the first time since the accident.

“I’m discovering how my mind can control these high levels of pain and bring them down,” he says. He finds it particularly helpful to replace his fears with more positive “comfort” images and messages; Once an avid boater, Michael Cross often imagines himself fishing on a pretty boat at sunrise, something he hopes to do again one day.

This new method of pain reprocessing addresses catastrophizing more directly. The study in which Dan Waldrip took part compared PRT with a placebo (saline injection) and with no treatment in 150 people with long-term chronic back pain. During eight one-hour sessions spread over four weeks, participants became aware of how easily the brain influences pain perception.

As in Spaulding, they also learned to reevaluate the feelings they were experiencing by making movements they thought were dangerous. For example, Dan Waldrip was asked to sit in an uncomfortable chair and describe in detail the pain it caused him. As he now understood that it was from a false alarm, the pain dissipated before he even finished describing it.

About 66% of pain reprocessing therapy patients in Yoni Ashar’s study had little or no pain at the end of eight sessions. This figure was 20% in the placebo group and 10% in those who received no additional care. A follow-up exam took place a year later and the results still held up. “PRT aims not only to reduce but above all to eliminate pain through psychological treatment”, something that no one thought possible, explains Yoni Ashar.

The study took functional MRI scans of patients’ brains while they were thinking about their back pain. According to Yoni Ashar, by the end of the study, three frontal regions involved in threat assessment showed reduced activity: the alarm bells causing their increased pain had been silenced. He adds that additional PRT clinical trials are underway, to treat other types of pain and to study minorities.

Another type of treatment, emotional awareness and expression therapy (EAET), aims to lift the veil on unresolved emotions that could be the cause of chronic pain in some people, says Mark Lumley. Caused by trauma such as childhood abuse or pressure to become a role model child, emotions such as anger and shame can be “a driver of the brain’s warning mechanism” that triggers physical pain.

EAET allows patients suffering from chronic pain to become aware of and express these feelings, either in a group or in individual sessions. Although the research is still in its infancy, a study comparing this type of therapy to cognitive-behavioral therapy in a cohort of 50 male veterans suffering from chronic pain found that in a third of those in the former group, the pain was reduced by half, while no patient in the other group obtained this kind of result.

Mark Lumley believes this new therapy could prove particularly valuable for people with fibromyalgia or irritable bowel syndrome for whom pain is the main symptom and not the consequence of another illness. “In this category, I would say that the majority of people have a psycho-emotional driver that contributes to their pain in a substantial way,” he comments.

But whatever the technique used, Mark Lumley above all wants the objectives in terms of treating chronic pain to be much more ambitious than they currently are. “Too many pain clinics say, ‘We can help you learn to live with your chronic pain,'” while doctors dealing with other seemingly incurable illnesses like post-traumatic stress disorder do everything their best to make the disease disappear completely, he laments. He says tackling catastrophizing is a crucial strategy to achieve this.

Specialists would also like the pain catastrophizing scale not to be used only to evaluate patients suffering from pain for a long time, but also to be used to preventively identify patients whose pain risks becoming chronic.

“At Duke, we now identify patients before surgery […]. So far, it’s phenomenal, says Padam Gulur. I can take a look at the score and have an excellent intuition that by investing in preventive and prophylactic measures for this or that person, the outcome for them will be much different than it would have been otherwise. »