The DNA of contemporary humans, like a multi-millennial archive, contains valuable information about our ancestors. By examining the sequences specific to the paternal and maternal lines, it is possible to retrace their history. Geneticists can thus reconstruct the demography of populations of the past, by focusing for example on the Y chromosome, present only in men and transmitted from father to son. In doing so, they noticed that paternal genetic diversity, and therefore of the Y chromosome, globally and suddenly collapsed between 3,000 and 5,000 years ago, during the Neolithic, while maternal diversity remained stable. To explain this phenomenon, the dominant theory was based on a principle of violence: clans engaged in territorial wars which led to the death of many men, and therefore a decline in the diversity of their chromosome. But, recently, Léa Guyon and her colleagues from the National Museum of Natural History, in Paris, the CNRS and the University of Paris Cité, put forward a new hypothesis, rather based on a change in the social organization of humans at this time. era, towards a so-called “patrilineal” structure.

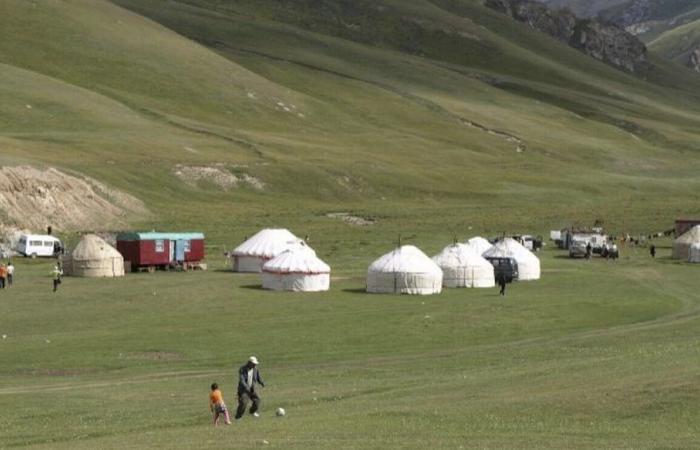

These scientists propose that as humans gradually abandoned their hunter-gatherer lifestyle for an agropastoral model, their social organization also changed. From a predominantly bilateral system, in which individuals are affiliated with both their maternal and paternal families, they would have transitioned to a segmental patrilineal system, in which populations are organized around the paternal lineage, then fission when they become too large, in sub-lineages made up of very closely related men, such as brothers and cousins. In other words, men from the same family kept to themselves and married women from other lineages, which prevented the spread of their genes and favored the homogenization of the Y chromosome. In a study conducted in 2008, a team showed that in segmental patrilineal populations in Central Asia, the diversity of the Y chromosome is lower than in non-patrilineal populations.

Léa Guyon and her colleagues therefore wanted to verify which phenomenon can best explain the loss of diversity of the Y chromosome in the Neolithic. To do this, they simulated the genetic dynamics of an initial population of 1,500 individuals divided into five villages and looked at the genetic diversity over a large number of generations. They considered two scenarios. One, warlike, in which each generation saw 15% of men disappear due to war, and the other, non-violent, in which certain clans grow to the detriment of others, through their segmental patrilineal organization. Result: the segmental patrilineal model caused a more drastic reduction in Y chromosome diversity than the model based on violence. It could therefore be that the story of this sudden bottleneck of paternal genetic diversity is much more peaceful than the dominant theory so far has predicted.

Other factors may also have influenced the loss of Y chromosome diversity in the Neolithic. One of them is that of waves of migration. In particular, 4,500 years ago, the Yamnayas, a people of the Central European steppes, moved to Western Europe and Central Asia. The Y chromosome of the Yamnayas has spread widely among local populations. The model of Léa Guyon and her colleagues does not take into account the effect of these migrations, but, according to the researchers, if the Yamnayas had a segmental patrilineal organization before their arrival, this could explain why their genetic heritage changed. is effectively spread to the detriment of others.

Download the PDF version of this article

(reserved for digital subscribers)