⇧ [VIDÉO] You might also like this partner content

A new treatment based on induced pluripotent stem cells restored vision in three patients suffering from severe eye disorders that clouded the cornea. The patients’ visual acuity was significantly improved, even one year after transplantation. Furthermore, no immune rejection was observed after the procedure (during the two-year follow-up period), even in those who did not receive immunosuppressive medications.

The cornea is surrounded by stratified epithelial tissue essential for vision. The layer located at the level of the limbal ring (the dark ring surrounding the iris) constitutes a reservoir of stem cells ensuring the continuous renewal of the epithelial cells making up this tissue. Limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) causes clouding of the surface of the cornea with fibrous scar tissue, which can lead to vision loss.

DCSL is either of immune origin, genetic (bilateral DCSL), or traumatic in origin (unilateral DCSL). Treatment of the disease generally involves removing the scar tissue clouding the cornea and transplanting healthy epithelial tissue. The choice of material to transplant, however, depends on the type of disease. For unilateral DCSL, the standard procedure consists of an autologous transplant, that is, using tissue from the patient’s own healthy eye. In contrast, treatment of bilateral DCSL involves transplanting limbal stem cells from deceased donors, or epithelial cell sheets cultured from the patient’s oral mucosa.

These approaches have many disadvantages linked mainly to uncertainty regarding the success of transplantation and the risk of immune rejection. On the other hand, neovascularization after transplantation of oral mucosal epithelial cell sheets is inevitable, which may lead to postoperative complications.

The study leading to the treatment, co-led by Osaka University (Japan), proposes a new approach based on induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, the potential of which has so far not been explored in the framework of the treatment of DCSL. “ To our knowledge, this is the first use of iPSC-derived corneal epithelial cells in transplantation surgery », indicate the researchers in their document, published in the journal The Lancet.

Persistent improvement in vision after one year in 3 out of 4 patients

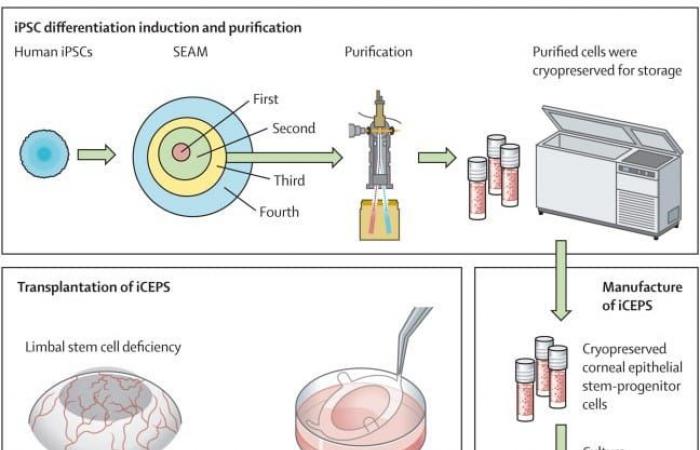

To carry out the tests, the Japanese researchers used iPS produced from blood cells from a healthy donor. iPS can be produced from any cell which, once genetically reprogrammed, can return to an embryonic state and then differentiate into all kinds of cells. The team cultured the iPS to obtain a thin sheet of corneal epithelial cells.

The leaflets were surgically transplanted in 4 patients, including a 44-year-old woman (patient 1) and a 72-year-old man suffering from idiopathic LSCD (patient 3), a 66-year-old man (patient 2) suffering from pemphigoid of the ocular mucosa (an autoimmune disease leading to the appearance of scar tissue in the conjunctiva and cornea) and a 39-year-old woman (patient 4) suffering from toxic epidermal necrosis (a skin condition similar to extensive burns and which can cloud the cornea).

Schematic of the whole procedure, starting with the cultivation of iPSCs and subsequent purification of corneal epithelial progenitor stem cells using a cell sorter. These cells were cryopreserved prior to manufacturing into iCEPS in a professional-grade gene, cell and tissue product manufacturing facility, and subsequent transplantation of iCEPS into affected eyes following removal of connective tissue in the patients with LSCD. © Takeshi Soma et al.

The procedure was performed by scraping the layer of scar tissue from the damaged eye, suturing the epithelial layers over the scraped area, and then placing a soft protective lens to isolate the area and promote healing. Patients 1 and 2 benefited from low-dose immunosuppressive treatment (cyclosporine), while patients 3 and 4 did not. All was followed over a period of 52 weeks, with an additional one year of safety monitoring.

After transplantation, all patients experienced an almost immediate improvement in their vision and a reduction in the area of opacified cornea. At 52 weeks, these improvements persisted and visual acuity was significantly improved. However, one of the patients showed slight recurrences after one year of observation. “ Overall, the beneficial efficacy results obtained for Patients 1 and 2 were better than those obtained for Patients 3 and 4 », Indicates the team.

See also

It is not clear what caused the improvement in vision, but it is possible that it was due to the proliferation of transplanted cells or the removal of scar tissue during surgery. The grafts can also trigger the migration of patients’ healthy cells from other areas of the eye, thereby “rejuvenating” the cornea.

No transplant rejection, even without immunosuppressive treatment

Additionally, the team recorded 26 adverse events during the 52-week follow-up period, but no serious side effects. No symptoms of graft rejection or tumorigenicity were observed after two years, even in patients who did not benefit from immunosuppressants.

According to Kapil Bharti, a translational stem cell researcher at the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, “it is important and relieving to see that the grafts were not rejected.” However, more trials are needed to confirm that the intervention is safe. The team is planning other clinical trials for this purpose starting next March.