Titre : The Book of the Road to the East

Authors: Clément Heinisch

Editions : The word and the rest

Release date: August 23, 2024

Genre : Roman

In 1998, when France had just won the football World Cup against Brazil, Clément Heinisch, 21, and his friend Jacques set off hitchhiking. Their goal was to reach Persia, Iran, borders at which they would have to stop their journey, in a somewhat confused manner, to begin their return to French soil.

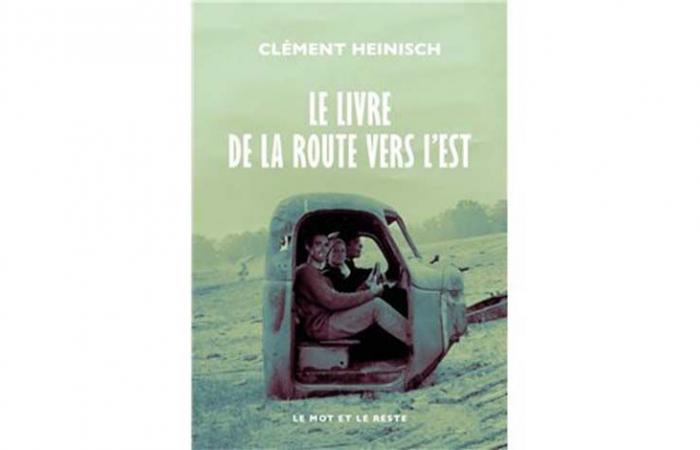

When we decide to read The Book of the Road to the East hanging by the cover, three young people in the cockpit of a broken automobile/flying machine, in a saturated green color, we imagine holding in our hands a mix between Jack Kerouac (whose author makes reference once) and Nicolas Bouvier (and his Usage du monde). We fantasize about discovering difference, difficulties, riches, encounters. All of this is, of course, discussed in The Book of the Road to the Eastexcept that one thing we hadn’t imagined was the writing style that would go with it.

Clément and Jacques are French knights, not on a crusade against the Barbarians, but knights who defend, through Clément’s pen, a limitless imagination, an admiration of the Middle Ages, an incessant, excessive formal invention, never stopping. A sentence, page 10, among hundreds of others: “But the pedestrian and mystical path proper to the wise, the geniuses and the saints is far from being reached, at a time when the respective natures of the two companions boil like oceans of lava where iron hands pour out sections of ice floes & constellations.”

Faced with such an exuberant style, there is only one thing to do. Either put the book back on the shelf where it was just taken out, or get involved in the game. If you accept the approach, there is sincerity that emerges, a lot of self-mockery (coupled with a rather paradoxical chauvinistic big neck), and a certain love of the French language (which is openly expressed at the end of the book).

There is still a lot of irritation in reading, of sighs (“what am I reading here?”). Some sentences themselves get lost in the mountains. The author plays so much with himself and his tale of valiant knights that it is difficult to distinguish the true from the false, even though we know full well that a travel story is sometimes nothing more than hyperbole and fantasies of what really happened. Here, we do not even necessarily always understand the course of the action. The bawdiness, never hidden, is tiring, and at the same time a little called into question.

We then remember that the companions were in their early twenties. This is perhaps where this constant impulse to describe themselves as supermen comes from (for Jacques, a superman who mourns his Marie who is kindly waiting for him at home). If we accept all these stylistic constraints, if we go beyond them, if we see them as a game of adolescents/children who perhaps think they are renewing travel literature in their wildest dreams, we can open ourselves to this travel story that energizes formal codes. The book is made up of rich encounters and funny situations (the discovery of collective latrines), shares a desire to learn more about Turkey and these countries to the East that border it (the writing is sometimes so nebulous that it is complicated to refer to the book for any geographical traceability), as well as about these Kurdish and Armenian peoples who live there, and whom the two boys met on their way.