Book –

Jean-Charles Giroud stars with Genevan Noël Fontanet

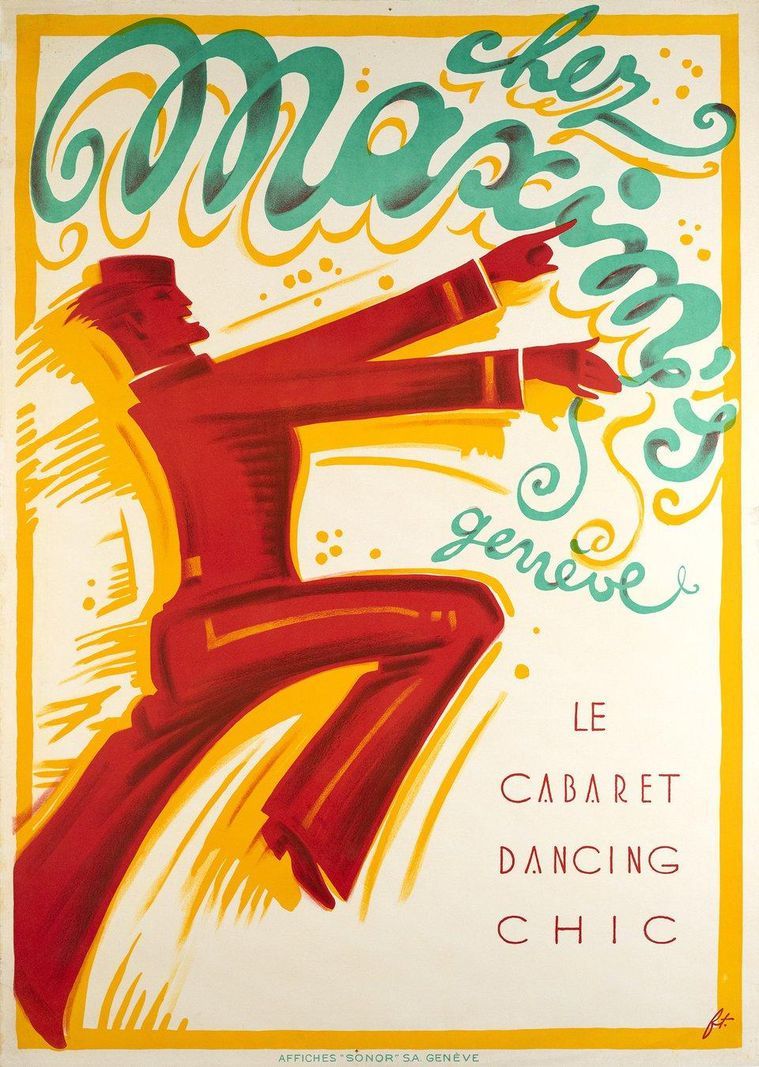

A highly illustrated work tells the story of the advertising man and the far-right man who marked the local landscape in the 1930s.

Published today at 4:18 p.m.

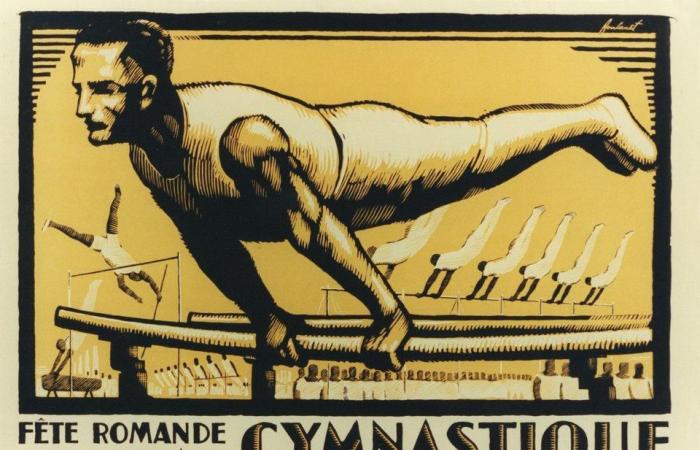

A sporting festival treated like a wood engraving.

Estate Noël Fontanet, Gallery One two three.

Subscribe now and enjoy the audio playback feature.

BotTalk

The name remains known in Geneva and its immediate surroundings. As for the first name, things seem less obvious. Since Christmas, which is now the subject of a beautiful book, his son Guy Fontanet, with the physique of a bull bull, has served on the Council of State. Guy’s daughter-in-law, Nathalie has chaired the same executive since this year, where she brings a little blondeness. I also knew two other sons of Noël, Hugues the antiques dealer, and especially Jean-Claude, the successful writer who has been forgotten. Suffice to say that the uninitiated gets lost in the branches of the family tree, where the poster artist acts as a common core. It took the erudition of Jean-Charles Giroud, former director of the Geneva Library, to clear the ground. Many of Noël Fontanet’s works remain to be found. The catalog raisonné proposed at the end of the volume includes around 400 numbers (the method of calculation adopted remains unclear) out of the approximately 1400 (or even 1700!) pieces that the man claimed to have created at the end of his life.

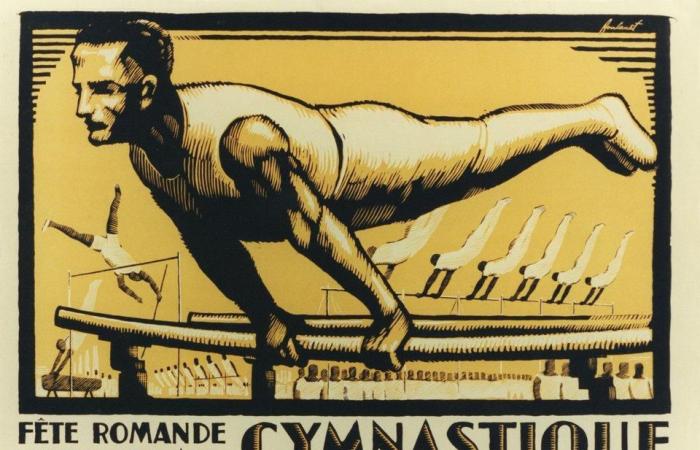

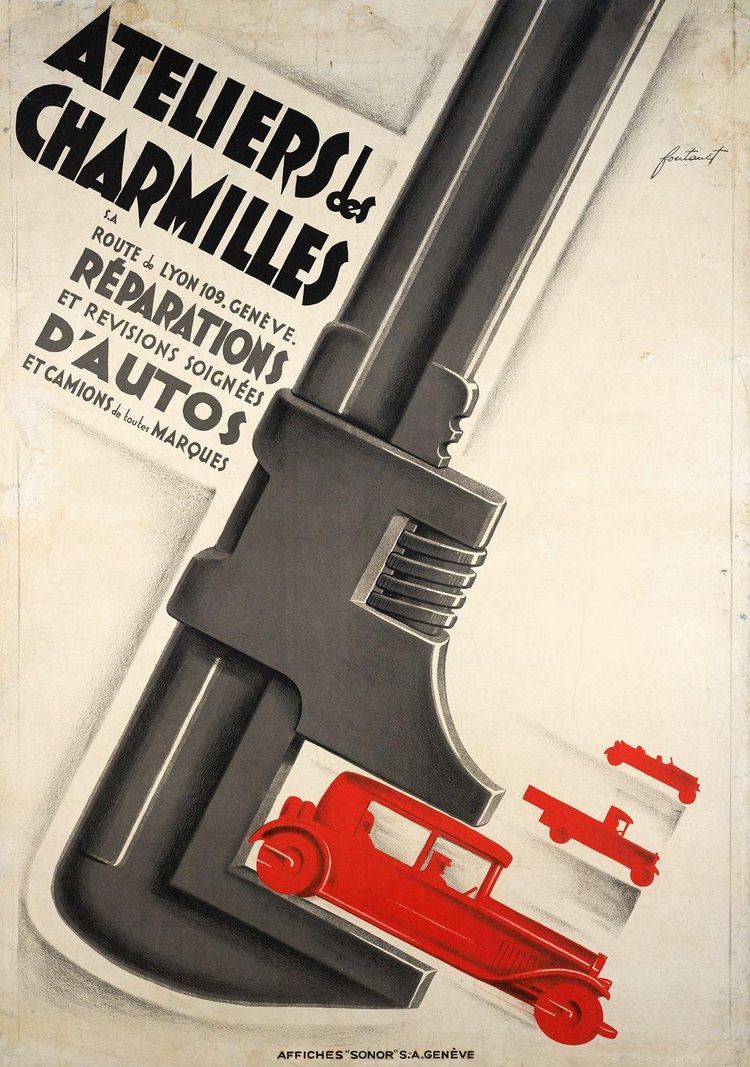

An Art Deco layout for the Ateliers des Charmilles in 1929.

Estate Noël Fontanet, Gallery One two three.

Fontanet was initially a second-generation Italian immigrant. Born on December 24, 1898, hence his middle name, Savino Fontaneto was one of the people who assimilated so well into their host country that they ended up becoming more royalist than the king through xenophobia. Naturalized in 1930, the graphic designer quickly turned to an exacerbated nationalism during what was called, following a famous series of broadcasts for TSR by Claude Torracinta, “Le temps des passions”. After socialist beginnings, he adopted an ever more extreme right, following his “ultra” friend Georges Oltramare before the war. Geneva then found itself split in two, with “the reds” in the other camp led by Léon Nicole and Jacques Dicker (whose great-grandson is called Joël Dicker). The peak was reached during the shooting of November 1932, but then there was the government of the left, then that of the right. There was a lot of political zigzagging in Geneva in the 1930s, while the state coffers remained empty.

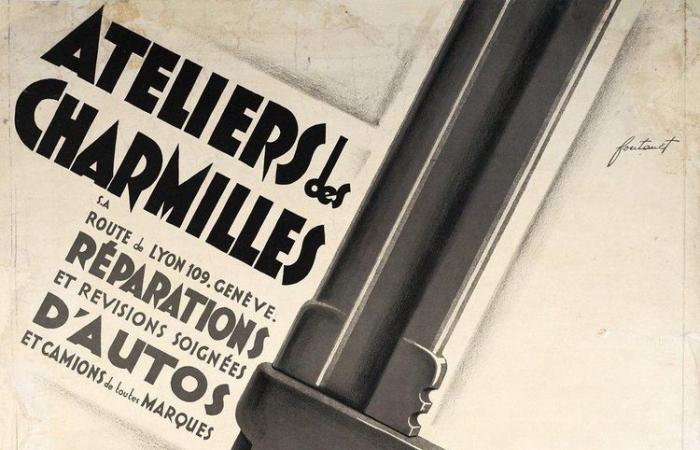

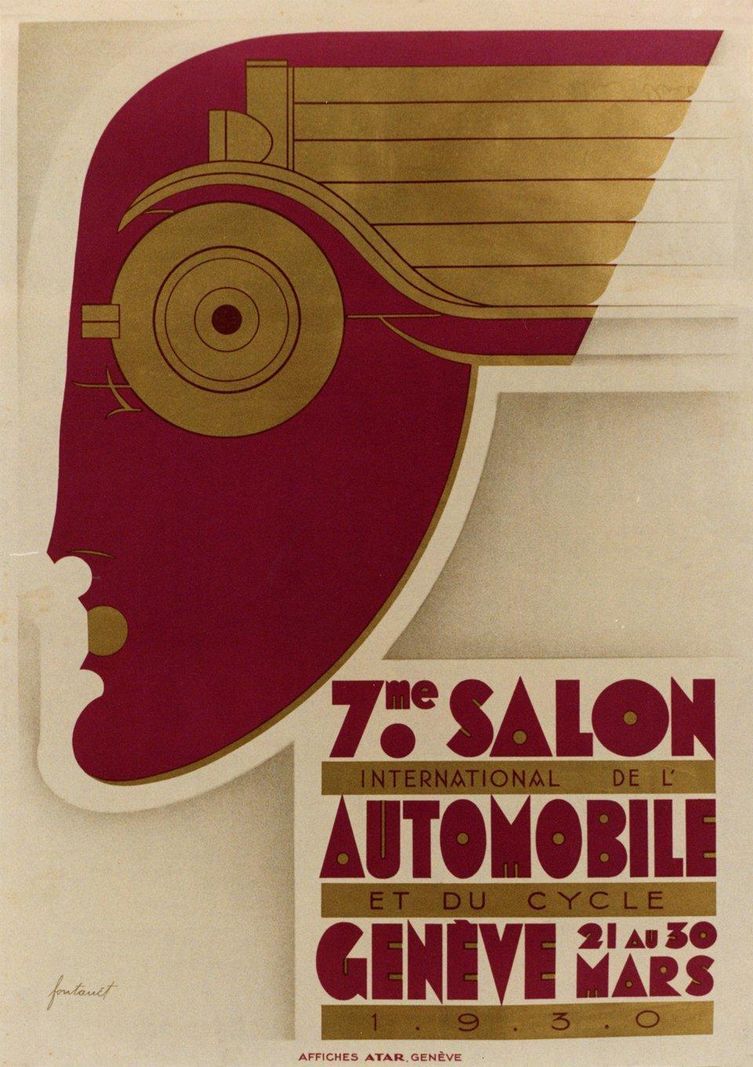

The 1930 Motor Show. The poster exists in different colors.

Estate Noël Fontanet, Gallery One two three.

Largely self-taught, to the extent that he completed his education on the job with a brief internship in Paris, Noël Fontanet began producing in the 1920s. Above all, commercial. The polemical aspect, which was to come later, barely covers a quarter of the known work. Our man was also a cartoonist, working in particular for “Le pilori”, a local newspaper that was often anti-Semitic (1). Unlike many of his local colleagues (from Henri Fehr to Jules Courvoisier), he did not pursue a parallel career as a painter. For him, the poster constituted a primary vocation, with what it supposes to be synthetic. A simple image, because it is stylized. Clear, but quality graphics. A striking message in that it is received like a punch. The Art Deco then in vogue facilitated the union of these three qualities. It is also worth noting (which Jean-Charles Giroud does not do) that Fontanet will never be able to get out of it. The post-war period, however, favored other styles. Our artist thus found himself a latecomer around 1950, then frankly out of date in the 1960s, when he had become the leader of Vigilance, the new far-right party.

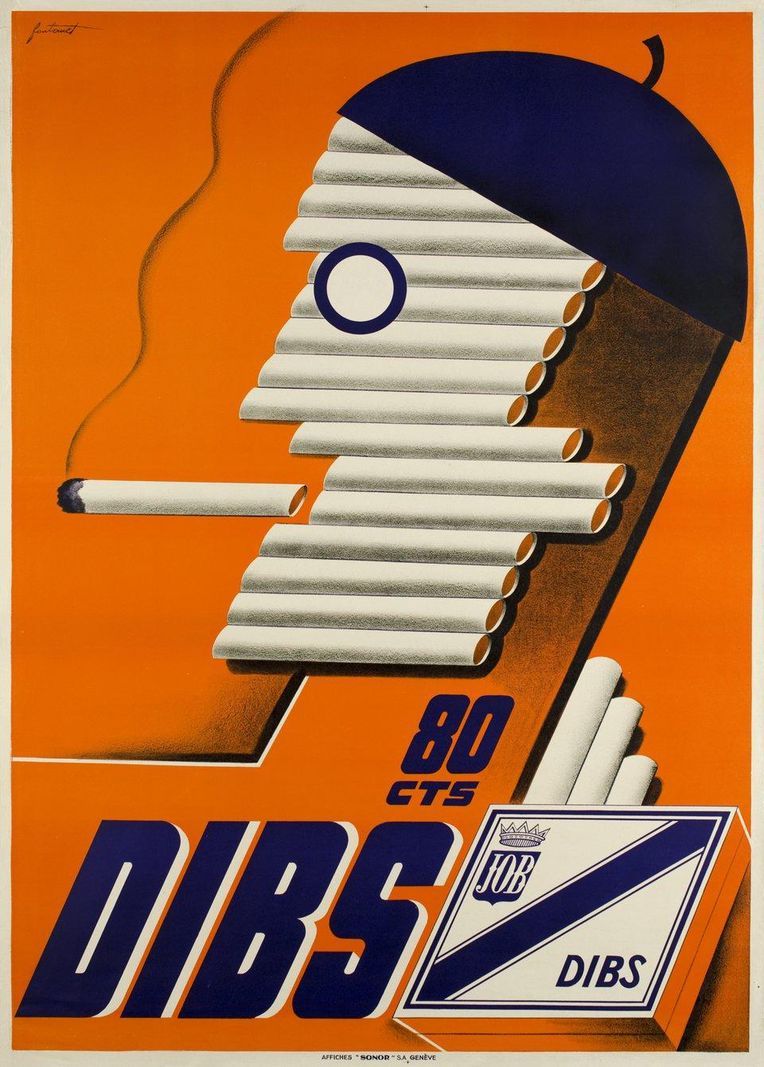

Fontanet worked a lot for tobacco companies. Note the package price!

Estate Noël Fontanet, Gallery One two three.

Before that, there had been excellent, good and average. Working on a very small site, even if he received a few orders from Neuchâtel or German-speaking Switzerland, Noël Fontanet had to accept everything and therefore anything. In other words, jobs offered by clients who are either broke or of questionable taste. The thing is evident in the result. If the poster for the 1930 Horse Show forms a masterpiece worthy of any museum, if that for the Atelier des Charmilles remains a marvel of invention, there are many unmentionable things in the catalog raisonné . Their current rejection does not come from their political or social character (the nine successive posters against women’s suffrage, for example), but from their poverty of imagination and execution. Fontanet often recycles an old idea due to lack of time by simplifying the form and botching the printing. Time is money after all!

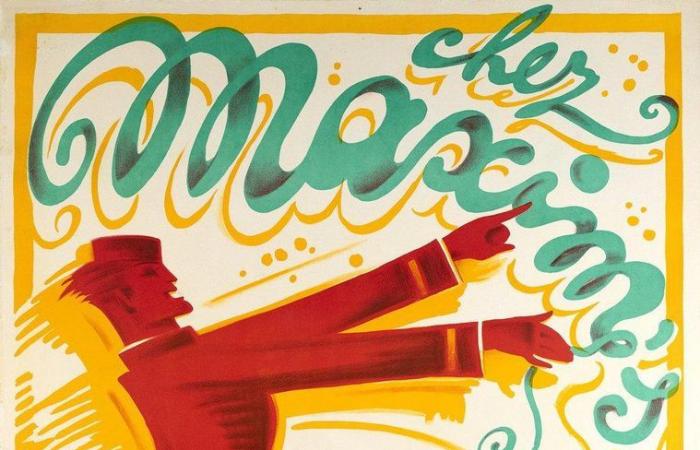

Fontanet’s poster looks more at French creation than at Germanic experiences.

Estate Noël Fontanet, Gallery One two three.

Jean-Charles Giroud retraces with great knowledge this long trajectory, which came to an end by drying up around 1970. Fans also know that he remains the greatest connoisseur of the Swiss poster with Jean-Daniel Clerc, the director of Eaux-Vives from the formidable specialized gallery “Un deux trois”. The stylistic side thus mixes with the biographical aspects, which prove very important here. The author knows how to detach the key pieces from those that make ends meet difficult. Above all, he can place Fontanet in his time, which marks the second apotheosis of the Swiss poster after the fireworks of the 1910s. The Genevan thus has nothing to do with what was being created at the same time in Basel or in Zurich, sometimes already with printed photography. He remains closer to the France of Charles Loupot and especially Cassandre. From Mussolini’s Italy too, which he admired from afar. Hence a side that is unavoidable in our time where it is appropriate to remain morally white as snow, even if some pass through the drops (or in this case the flakes). The most surprising thing for Giroud is to note that if there is a direct descendant of Fontanet in Geneva, it is in full awareness the very left-wing Exem. The tentacle octopus man. But after all, if politics knows its colors, graphics primarily constitute a design.

A 1953 poster against women’s suffrage.

Estate Noël Fontanet, Gallery One two three.

(1) Fontanet nevertheless created beautiful posters for all the Geneva department stores belonging to Jewish families for a long time. And he will give placards for the socialists under an assumed name…

Practical

“Noël Fontanet, Master of the Swiss Poster” by Jean-Charles Giroud, Editions Slatkine, 262 pages. Be careful, heavy book!

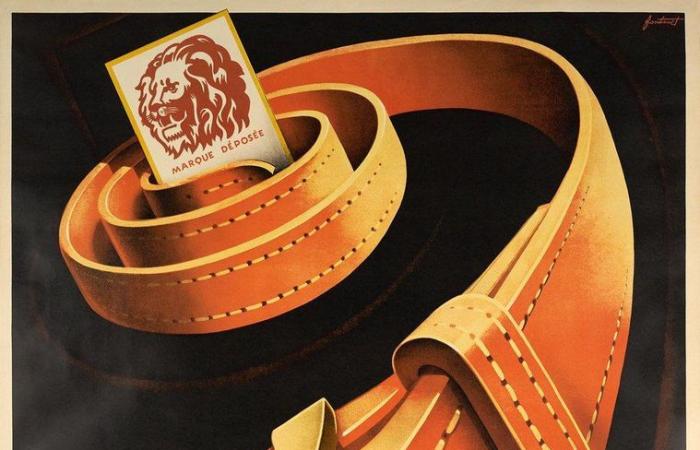

A rare foray by Fontanet into highlighting the object. A very German-speaking trend.

Estate Noël Fontanet, Gallery One two three.

“Etienne Dumont’s week”

Every Friday, find the cultural news sketched by the famous journalist.

Other newsletters

Log in

Born in 1948, Etienne Dumont studied in Geneva which were of little use to him. Latin, Greek, law. A failed lawyer, he turned to journalism. Most often in the cultural sections, he worked from March 1974 to May 2013 at the “Tribune de Genève”, starting by talking about cinema. Then came fine arts and books. Other than that, as you can see, nothing to report.More info

Did you find an error? Please report it to us.