Book –

Bernadette Murphy invites us to sit at “Café de Van Gogh”

The English historian gives a fascinating (and surprising) work on the sociability of the painter during his stay in Arles.

Published today at 9:14 a.m.

Bernadette Murphy, who revolutionized the biographical approach to Van Gogh.

DR, Actes Sud.

Subscribe now and enjoy the audio playback feature.

BotTalk

This was in the years before Covid, in other words for some of us before Christ. Unknown to the battalion, Bernadette Murphy published her essay on “Van Gogh’s Ear” in 2017 with Actes Sud. Having lived in Provence for decades, the English historian published her first work at the age of 54. It focused on a subject that we thought had been exhausted by so many titles about the painter. An Anglo-Saxon woman was undoubtedly needed to return to the archives instead of launching into speculative delusions about the work and its author. Until her, what had been said to be biographical in the first half of the 20th century had taken on the value of gospel. Didn't we have hundreds of letters sent by Vincent to his brother Theo?

“Lust for life” in 1956 with Kirk Douglas. Van Gogh becomes a romantic cinema hero.

DR.

However, by digging a lot, the author discovered that everything was factually false in the case of the severed ear. She had been “romanticized.” Bernadette Murphy sees it today as a perverse effect of the biography of Irving Stone at the time when it was brought to the screen in 1956 by Vincente Minnelli with Kirk Douglas as Van Gogh. An excellent film otherwise. The legend then replaced a simpler and more trivial reality. The amputated ear had not been given to a brothel girl, but to a young waitress that Vincent knew a little. And it was still a bloody fragment. Everything else was in line. Bernadette, who lives in the region, took years to put together a file including every inhabitant of Arles in 1888. Some 20,000 cards… Readers did not ignore the book, which was a hit. An icon of art history revealed itself to them in a new light.

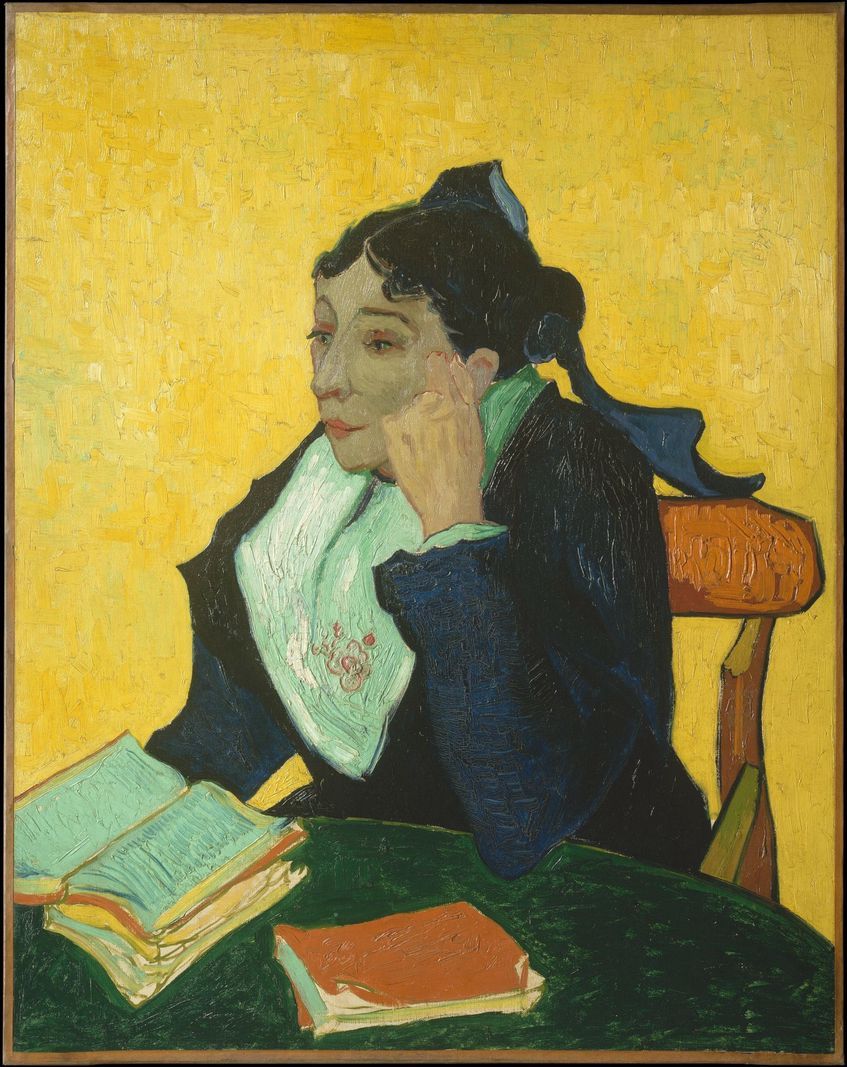

Marie Ginoux. It was at the heart of the relationships that Van Gogh maintained with the Arlesians.

DR.

Bernadette Murphy was able to bring out her files for “Le Café de Van Gogh”, which Actes Sud is launching these days. She refined them at the cost of considerable work in order to prove that the painter lived in a network from the moment he arrived by train in Arles. The people portrayed by a Dutchman whom no one had ever seen here knew each other. They developed family ties or commercial relationships. Many shared political ideas, more on the left. Vincent therefore saw himself recommended to one by the other. This played a role in the changes in accommodation that Van Gogh found easily. She allowed him to plant his easel in the open field, which required permission from the owners. Or to paint a young girl of thirteen or fourteen. Even if he started to scare after the ear affair and the internment, Van Gogh made a few friends after a good first contact. Some remained in contact with him until his suicide in 1890. The very recent mass literacy in France had made mail possible (1). Finally, there was the link with the pastor of Arles, which then had a strong Protestant community, and the link with an exceptional doctor. Not only did Doctor Félix Rey save him from death by infection, but he wrote to Theo to give news.

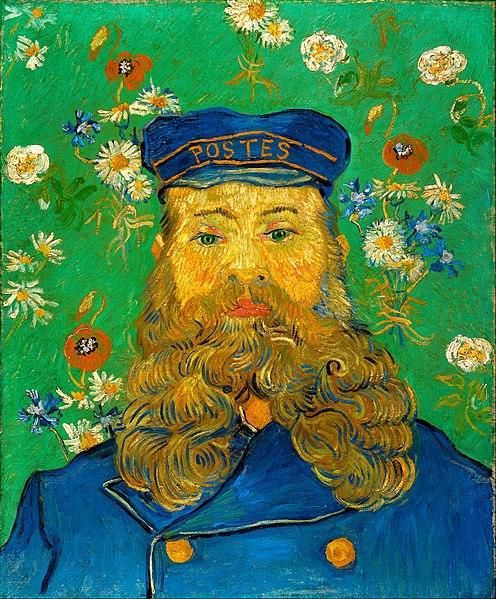

Joseph Roulin. The most faithful friend.

DR.

All this forms only the relief part of a very good (and very long) book on a famous man. In the background, Bernadette Murphy shows us a poor, fairly isolated town, where the main employer is the railway. Everyone knows about it, even if people hardly leave their neighborhood. There is the shackles of propriety. No one would dare to contravene it. The reader feels this clearly in this work where each person painted by Van Gogh is the subject of an in-depth biography. These are small lives, with no real horizon. However, sometimes these are long existences. If Van Gogh never painted the portrait of the Arles supercentenarian Jeanne Calment, the last of his models died in his nineties in 1980. Van Gogh showed her to us as a baby. Bernadette Murphy tells us how she went to visit his grave after having difficulty locating it. “Van Gogh's Café” is also a book about the author at work. The woman writes in English. Slowly, she said. So he sometimes has to explain to his compatriots how deep France works. Arles becomes Arles again when the summer tourists have left.

Camille Roulin, whose sad existence Bernadette Murphy tells us about. He will become a war invalid.

DR.

On the last page, the reader knows a little more. The central figure has taken on substance thanks to the presence of a fascinating background. Van Gogh does not remain alone on stage. His voice is now part of a polyphony. Is there still anything left to say now? Or would the subject be inexhaustible?

(1) One of his acquaintances made his young son hold the pen. Camille Roulin had beautiful writing. This little farmer made almost no grammar or spelling mistakes…

Practical

“Van Gogh's Café”, by Bernadette Murphy, translated by Marie Chabin, Editions Actes Sud, 400 tightly packed pages.

“Etienne Dumont’s week”

Every Friday, find the cultural news sketched by the famous journalist.

Other newsletters

Log in

Born in 1948, Etienne Dumont studied in Geneva which were of little use to him. Latin, Greek, law. A failed lawyer, he turned to journalism. Most often in the cultural sections, he worked from March 1974 to May 2013 at the “Tribune de Genève”, starting by talking about cinema. Then came fine arts and books. Other than that, as you can see, nothing to report.More info

Did you find an error? Please report it to us.