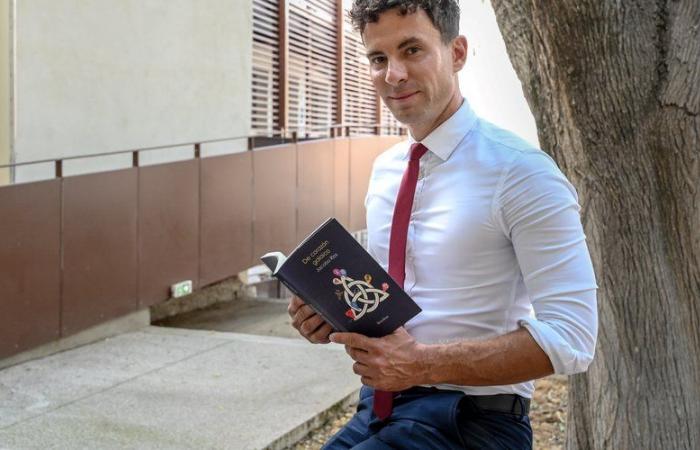

His novel Corazon galaico reveals his Galician origins. But, in this work awarded the Prix Méditerranée Roussillon 2024, the young dean of the Perpignan law faculty weaves a true adventure story from Celtic legends to Perpignan’s religious heritage. Jacobos Rios opens up.

How would you define this Corazon Galaico (Galeic heart) awarded the Prix Méditerranée in Perpignan?

It is a novel of adventure and mystery which takes place between two countries: France and Spain. It begins in Paris and ends in Galicia. I also wanted chapters in Perpignan. A foreign student in France, a common starting point with my story, meets a professor of a rare specialty, Celtic law. This professor got it into his head that before the arrival of the Romans there already existed a legal system. This teacher is French, Breton. He suggests that the student go in search of a mythical object, the existence of which is not certain. It’s a book. Its discovery can change the entire paradigm. It is both the story of a quest, but also the story of a transformation for the student.

Is this book also a journey?

Yes, it evokes Celtic, Galician and Pyrenean legends. The cathedral and the natural history museum, with its mummy, of Perpignan are key sites of this adventure. But, when we see reality with other eyes, these places also change.

“This book tells how we leave an ordinary life to enter an extraordinary world”

Is there any history of yours in this journey?

A bit, I was also an Erasmus student. It was thanks to Erasmus that I arrived in Paris, that I learned French, the central character of the book too. I know all the places that appear in the novel. But, I have not had a Celtic law teacher who suggested such a quest to me. This book also tells how we leave an ordinary life to enter an extraordinary world.

What are your literary influences?

Many and diverse. Not a particular author. It was classic French literature from the 19th century that inspired me to come to France, but I don’t think it directly influences my writing today. Corazon galaico is my first novel, but I have written a lot of books or legal articles on international law. One day, I said to myself why not write a fiction book, knowing that in my free time, I don’t read law books but fiction novels.

What does this Mediterranean Prize represent?

It’s incredible, it’s an honor. I really didn’t expect it. I wrote this novel in my natural language (Castilian) unlike my writings on international law which I write mainly in French. But when I wrote it and published it in Spanish, I didn’t know if there would be any attention in France. And, one day, André Bonet (creator of the Mediterranean Literature Center) contacted me and I was very pleasantly surprised by this interest in a book that also talks about here. For me, just publishing it was already a victory, so a prize…

A French translation is now missing…

It’s an idea of course. I would love it. If this allows us to reach a larger audience, I will be very happy. But, for the moment nothing has materialized.

The winners of the 2024 Mediterranean Prize

Mediterranean Prize : Some flowers by Colette Fellous (Gallimard)

Foreign Mediterranean: Song for Europe by Paolo Rumiz (Arthaud)

Mediterranean test: Venice, Veneto is a fable by Luisa Ballin (Nevicata)

Mediterranean 1st novel: The ideal conditions of Mokhtar Amoudi (Gallimard)

Mediterranean Spiritualities: Reconquering the Sacred by Sonia Mabrouk (The Observatory) and Francis of Assisi, the Knight Without Armor by Luc Adrian (Emmanuel)

Mediterranean Roussillon: From a Galician heart by Jacobo Rios (Hercules de Ediciones)