(New York) After climbing 377 steps, you reach the crown of the Statue of Liberty, from where you can see a date inscribed on the tablet that the great lady holds in the crook of her left arm: July 4, 1776.

Published at 00:31

Updated at 5:00 a.m.

Does this mean that the tablet represents the United States Declaration of Independence, which Americans will celebrate on the 248th?e birthday in a few days?

Reneel Langdon answers in the negative.

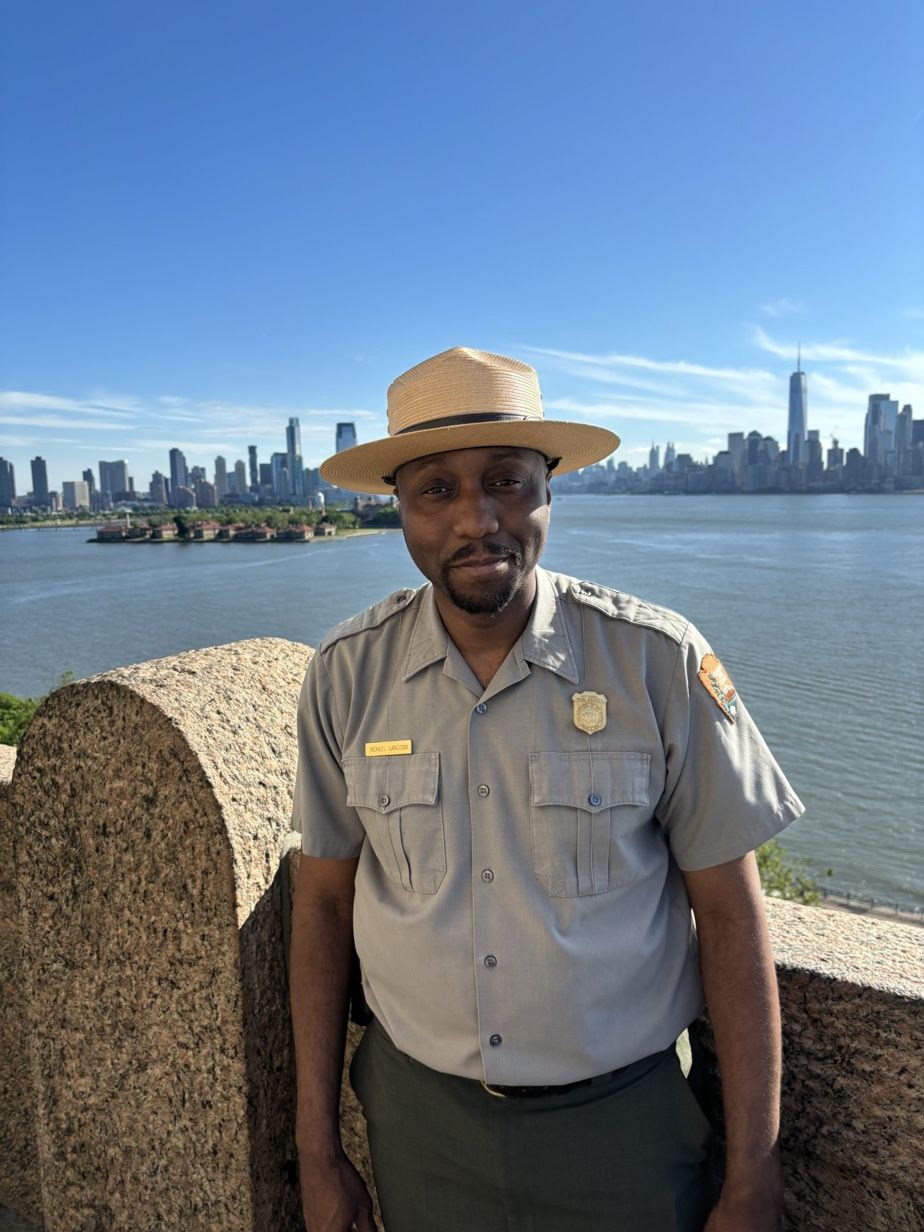

“The tablet is the symbol of the law, of the Constitution,” explains the ranger, wearing a wide-brimmed hat. “And in that constitution, you have the Bill of Rights, you have the tools to advance democracy—freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and so on—all the rights you need to fight against the chains of oppression.”

As the sun barely rises over New York Bay—and well before the first tourist boat arrives—Reneel Langdon speaks with a small group of foreign journalists atop a monument that embodies values that the United States has sometimes rejected over time, including freedom itself.

Three other similar groups will follow, trained by their own rangers. As luck would have it, ours is itself a symbol of sorts. Unlike its colleagues, it was born abroad, more precisely on the island of Grenada.

And today he works as a ranger supervisor at Liberty Island, a national park that houses the statue that 12 million immigrants passed by on their way to neighboring Ellis Island.

PHOTO YUKI IWAMURA, ARCHIVES ASSOCIATED PRESS

U.S. Navy officers stand on the deck of theUSS Bataan as he walks past the Statue of Liberty.

“It’s poetic,” he says, referring to his journey.

A journey that made him, at 42, an American citizen whose faith in the Statue of Liberty remains unshakeable, despite everything that is happening in his adopted country.

The most intense fear

This path took a distressing turn on September 11, 2001. Arriving in New York with his family shortly before this fateful date, Reneel Langdon had only just begun studying sociology at the Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC), whose main campus is located a stone’s throw from the World Trade Center.

He is still recovering from the culture shock of his new life in the American megacity when two planes hit the Twin Towers. He remembers the panic that gripped him after the iconic skyscrapers collapsed.

“I rushed home to Brooklyn. I was terrified that I was going to be in a city that was under such a massive terrorist attack. But when I got to the Brooklyn Bridge, it was closed. There was no subway. There were no buses. There was no way out of Manhattan. I felt the most intense fear of my life. And I told myself that I never wanted to feel anything like that again.”

That feeling led him to drop out of class at BMCC, where one of the buildings was damaged by the collapse of Tower 7 of the World Trade Center. And it prompted him to enlist in the U.S. Coast Guard, the fifth branch of the U.S. military.

I was assigned to an icebreaker off the coast of Maine. After 9/11, I felt like I needed some training. I needed it to feel stronger. I had just been through a terrifying experience.

Reneel Langdon

After leaving the Coast Guard, Reneel Langdon returned to New York, where he resumed his studies. And, shortly after earning an undergraduate degree in sociology from Hunter College, he began working at Liberty Island and Ellis Island.

The “movement” of history

Ten years later, Reneel Langdon is anything but jaded.

“To think that 12 million immigrants entered the United States through here and to have the chance to tell that story, as an immigrant, is pretty incredible. The poetic dimension of the situation is not lost on me.”

This word – “poetic” – comes up often in Reneel Langdon’s mouth.

A certain poetry permeates the way he describes the “movement” that the Statue of Liberty represents in his eyes. He first evokes the time when Édouard Laboulaye conceived the idea of the monument to commemorate the centenary of the Declaration of Independence of the United States. This French jurist and abolitionist does not only want to celebrate the endurance of American democracy, but also the liberation of the country’s slaves.

But, as Reneel Langdon points out, the work of French sculptor Auguste Bartholdi that stems from this idea was inaugurated in 1886, a dark moment for freedom in the United States. The Reconstruction period that followed the abolition of slavery was now a memory, having given way to laws institutionalizing racial segregation in the former slave states.

PHOTO RICHARD HÉTU, SPECIAL COLLABORATION, THE PRESS

For Reneel Langdon, the Statue of Liberty represents the quest for the American dream: “And the fight continues in different ways for different groups.”

“The irony is that the statue was unveiled in the midst of Jim Crow,” Langdon said, using the name given to the segregation laws. “That promise of freedom was not yet a reality for many African Americans. But at about the same time, Ellis Island opened and the first of more than 12 million immigrants passed by the statue, escaping poverty and persecution in search of the American dream.”

“For me, the Statue of Liberty represents that movement. And the fight continues in different ways for different groups.”

In fact, this movement of history manifested itself on the very day of the inauguration of the Statue of Liberty.

“Here are my rights”

“Suffragists rented a boat and came up to the island that day,” recalls Matt Housch, an archivist at the new Statue of Liberty Museum. “They held up bullhorns and gave speeches about how ironic it was that we were erecting a statue to a woman, to liberty, when they didn’t have the right to vote in the United States.”

The archivist says he recently collected the testimony of an artist from the Bronx who participated in another demonstration, this time on the island, in 1978. She accompanied Muhammad Ali, who was then taking up the cause of the American Indian Movement.

“I would feel guilty, as a wealthy person, if I didn’t help them,” the famous boxer said at the foot of the Statue of Liberty, referring to activists for the civil rights of indigenous people in the United States.

At the top of the monument, on a bright morning in June 2024, Reneel Langdon does not dare to answer directly the question of what inspires him in the current movement of history in the United States, where the great questions of democracy, freedom and immigration raise painful and troubling debates.

“I can’t speak to what’s happening right now, but I can say that’s why sites like this are important,” he said. “People can come and understand the back and forth of history and how a democracy works. Democracy swings like a pendulum. And Americans are fortunate to be able to stand on this law, on this Constitution, and say, ‘Here are my rights.’”

It’s poetic, according to Reneel Langdon. Or utopian, depending on the era.