The various carbon markets – which some qualify as the “right to pollute” – are roundly criticized for their complexity, their opacity and their ineffectiveness in effectively reducing greenhouse gas emissions at the global level. Despite these pitfalls, they nevertheless constitute a useful tool for financing projects in the countries of the South.

A first carbon market only concerns bilateral exchanges between States, and it is a mechanism that Switzerland particularly appreciates in its climate strategy: “Switzerland is one of the most dynamic countries, with other countries such as Singapore , Sweden or Japan”, confirms Christian De Perthuis, specialist in carbon markets and professor of economics at Paris Dauphine University.

The plan is quite simple: Switzerland finances reforestation or renewable energy projects in countries in the South and, on this basis, “we will calculate a certain number of emissions reductions financed thanks to Switzerland, part of which can be integrated into its contribution to the objective of the Paris Agreement,” he explains.

A second market concerns the sector of private companies, which can sell and buy quotas when they exceed their greenhouse gas emission ceiling. These companies therefore exchange the right to pollute tons of CO2, and prices evolve according to supply and demand. A quota, the equivalent of a tonne of CO2, is negotiated from 1 to around a hundred francs.

Law of the Jungle

But in the absence of regulation, these carbon credits and quotas exchanged do not really correspond to tonnes of CO2 avoided or sequestered. And some sellers inflate the positive ecological impact of their projects to sell as many carbon credits as possible, which corresponds to greenwashing.

According to numerous studies, the climate effectiveness of certain projects is also questionable, notably several projects financed by Switzerland, like a network of electric buses in Bangkok.

>> Read also about this: Controversy surrounding electric buses financed by Switzerland in Thailand

“The market for these projects does not reduce greenhouse gas emissions, it simply shifts the location where these emission reductions are made,” summarizes Christian De Perthuis.

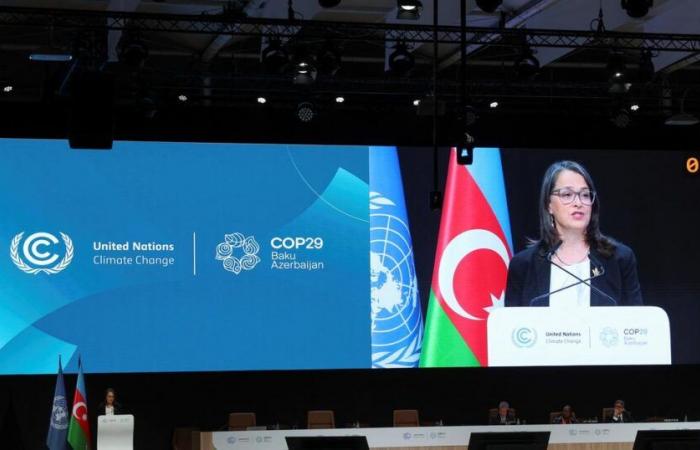

The current system is therefore unsuitable for the climate emergency and offers pollution rights to the biggest emitters, namely large companies and the economies of rich countries. It is therefore not a long-term solution. But this carbon market remains a way of financing the climate transition in the countries of the Global South. It remains to find the right formula with effective, transparent and impeccable carbon credits. This is what is at stake during this COP29.

Monday evening, a first international framework was accepted for a carbon market supervised by the UN. But it remains far from perfect in the eyes of many NGOs.