To understand this paradox, we must recall a simple equation: costs are the product of the unit price and the volume of services provided. If costs increase, this means either that prices have increased, or that the number of services provided is greater, or both.

Health, an exception in the rise in prices

To describe price developments in health or other areas of household spending, the OFS regularly publishes the consumer price index (CPI). The latter measures the increase in the price of goods and services in a standard basket representative of the consumption of private households in Switzerland. In this regard, around 100,000 prices are collected each month. These are grouped into 12 main spending categories, weighted according to the importance of each in the household budget.

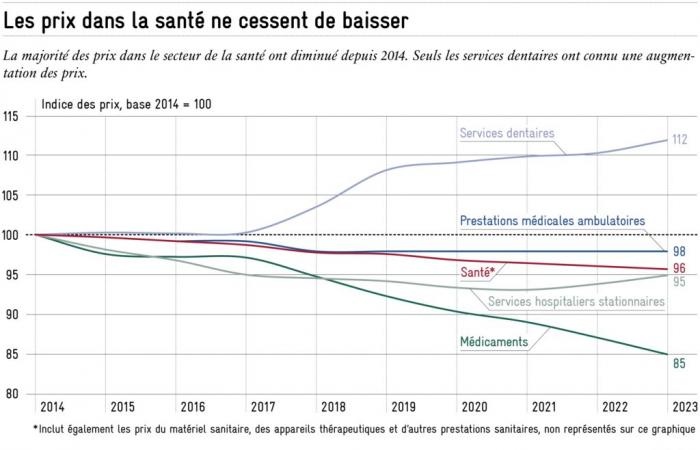

Health is one of these main categories. The category itself is broken down into several types of goods, such as medicines or therapeutic devices, and services, such as outpatient, stationary or medical office services. Overall, healthcare prices have fallen 4.4% since 2014 (see figure). This decline is all the more remarkable given that during the same period, the prices of the entire standard household basket increased by 5%.

For each health category, there has been a continuous decline in prices over the past ten years:

-- Prices for outpatient medical services fell slightly, with an average annual drop of 0.2%.

- Stationary hospital services saw their prices fall, then increase from 2020, a year marked by the start of the Covid pandemic.

- Medicines are the group that has seen the largest price drops since 2014 (annual average drop of 1.6%).

Dental services are the only exception. Their prices increased by 12% until 2023. While they were stable from 2014 to 2017, prices jumped in 2018 and 2019.

The volumes behind the costs

If the prices of health services decrease, the increase in health costs can only be explained by an increase in volumes, that is to say an increasing number of health services provided. Several reasons can explain this increase in volumes:

- The increase in population. It seems obvious that if the population increases, the services provided will be more numerous. But even considering only the costs per capita, these increased from 694 francs to 869 francs per month in ten years, which excludes this sole reason as a source of increase in total costs.

- The aging of the population. An aging population requires more medical care due to chronic illnesses and needs related to poorer health. We could therefore believe that the last year of a person’s life represents the largest share of health costs. However, this is not the case: the last twelve months of life represent “only” 10% of the costs covered by health insurance.

- Greater demand for health care. This increase is revealed in the figures: from 2012 to 2022, the proportion of people who consulted a doctor at least once during the year increased from 78 to 83%, and those who consulted a psychologist from 6 to 10%.

- Technological progress. The arrival of more effective therapies or innovative technologies can increase the number of medical procedures and costs. For example, a more effective and less invasive treatment could be prescribed to more patients, increasing total spending, even if the new treatment is less expensive per unit. Likewise, a breakthrough treatment for a previously incurable disease would generate new demand.

Do not lose sight of the cost/benefit ratio

Like technological progress, rising health costs are not necessarily problematic, as long as they result in greater added value for patients per franc invested. Regulation focused solely on prices could lead to an increase in unnecessary services, thus making the system ineffective. Conversely, a strict limitation of volumes without adjusting prices would risk causing rationing of care. Thus, only coordinated and coherent management of these two parameters will make it possible to achieve the key objective: an efficient health system, guaranteeing optimal quality at controlled costs.