The water question before Israel’s independence

In this environment with the Mediterranean or arid climate of Palestine, the question of water has always been significant. During the Ottoman era, irrigation was little, with the exception of the Jericho oasis (in the Jordan Valley) and the coastal orange groves (Jaffa oranges). Consumption, parsimonious, was controlled and shortages were exceptional. From the beginnings of Zionism, the question of water (and in particular the questions of irrigation and the production of hydroelectricity) were raised, notably by Theodor Herzl in two works [2]. This question was then used in 1919 to justify the Zionist claim to include South Lebanon in Mandatory Palestine. [3]matrix, for Zionists, of the future “Jewish national home”. From the beginning of the British mandate over Palestine, the use of the waters of the Jordan was envisaged as a means of developing the future “Jewish national home”; This is how, in 1923, a first hydroelectric dam was installed on the Jordan River south of Lake Tiberias. In the 1930s, the Yishuv [4]which functions as a proto-state, and the Zionist Organization [5]was the main tool of Jewish colonization in Palestine. set up water management structures, such as the Mekorot company (1936) and asked an American agronomist for a hydraulic development plan for the future Hebrew state, a plan which would be called the “Jordan Valley Authority”, based on the model of the “Tennessee Valley Authority”!

The beginnings of Israel’s monopolization of water resources

From independence, agriculture was considered a priority and the development of irrigation essential: in 1953, Israel undertook the construction of a canal to divert the waters of the Jordan from Lake Tiberias to irrigate the coastal plain. and the northern Negev, a project rejected by neighboring Arab countries who rightly see it as an arbitrary drain on common resources. However, Israel will take advantage of this to maximize its share at the expense of its neighbors.

The savage dispossession of the Palestinians (1967-1992)

The 1967 war was a real boon for Israel, which now controls one of the sources of the Jordan located on the Golan Heights and all of the resources of the aquifers in the West Bank, and intends to use all this water for its own needs. From the summer of 1967, water in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip was placed under military control (military order No. 92 of August 15, 1967). This military order revoked all drilling licenses previously granted by the Jordanian government and banned pumping from the Jordan River “for security reasons.” From the summer of 1967, Israel thus had total control over water resources and could use them to develop its colonization projects. The digging of new wells is therefore subject to authorization from the military authorities (authorizations very rarely granted: 37 in 30 years [1967-1996]while the Palestinian population has more than doubled). The depth of Palestinian wells is limited to 300 m, while Israeli wells can reach 1,500 m. In 1975, Israel installed meters on Palestinian wells to limit water consumption. The results at the beginning of the 1990s are clear: total water consumption in Palestine stagnated at just over 100 million m³ per year, per capita consumption was divided by more than two, the surface area irrigated agriculture has decreased significantly. Thus, “The time for water stopped in 1967 in the occupied territories” analyzes the Palestinian agronomist I. Mattar [6].

The Oslo Accords: validation of spoliation

The essential aspects of the agreements

In the “Declaration of Principles for Interim Self-Government Arrangements” of September 13, 1993 (sometimes called Oslo I) the water issue is only mentioned for the record. It is only in the preparation and in the second agreement (known as Oslo II, 1995) that this question is addressed. Several institutions are created:

-- a Palestinian Water Authority (PWA) has jurisdiction over water and sanitation issues,

- The Joint Water Commission (JWC) is composed equally of Palestinian and Israeli experts.

But these structures have no jurisdiction over zone C (which covers 61% of the surface area of the West Bank, but barely 10% of its population). The PWA is responsible for the distribution of water and sanitation in the West Bank, but has no power over the flows which are governed exclusively by the Israeli company Mekorot. The JWC is certainly equal, but all its members have a right of veto over its decisions, the Israelis do not deprive themselves of this! This is how most Palestinian projects are refused once, twice, three times, 10 times, or even more, which extends the completion times and increases the financial costs. Furthermore, if the water quotas allocated to Palestine are increased, the share of water allocated to Palestinians remains limited to 15% of total water production, while the latter represent 35% of the population living between Mediterranean and Jordan.

Acceptance of the water agreement by Palestinian negotiators

How, during the negotiations which resulted in the so-called Oslo II agreement, were the Palestinians able to accept such a lenient agreement? Journalist Aziza Nofal [7] gives us some keys. She was able to speak with a member of the Palestinian delegation which signed the Oslo Accords who points out several problems:

- the lack of expertise of the Palestinian delegation, in the face of a relevant Israeli delegation which had long considered the question of water as essential,

- the way in which the Oslo negotiations were conducted which led to the departure of Palestinian experts in the field of water, in particular that of Abderrahman Tamimi [8],

- the main objective of Palestinian policies which was to reach an agreement.

A. Tamimi emphasizes the flaws in the agreement, in particular the separation between the water supply of populations (network, distribution, billing, etc.) which is the responsibility of the Palestinian Authority and the water resource which remains under the control of Israel, who can open or close the floodgates. For him, Article 40 of the Oslo II agreement (relating to water and sanitation) is “the worst part of the agreement”.

And since the signing of the Oslo Accords, very widely rejected by all successive Israeli governments since 1994, the confirmation of total will has only been confirmed: while some [9] may have thought that, when Israel had carried out its ambitious seawater desalination plan, it could hand over to the Palestinian Authority the management of (at least) part of the West Bank aquifers, he rejected this hypothesis (2020 ) and proposed to the AP to buy desalinated water, the price of which is 3 to 4 times higher than that of water from aquifers…

Thus, the Palestinian delegation in Oslo agreed, de facto, to validate Israel’s total control over water resources, that is to say, to accept the dispossession of its own people, in the expectation of a final agreement… which never came.

Jacques Fontaine

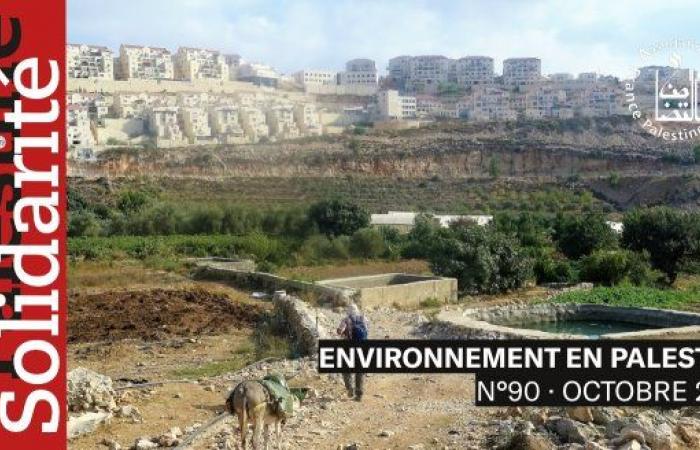

Photo: Water retention basins in Wadi Foukin