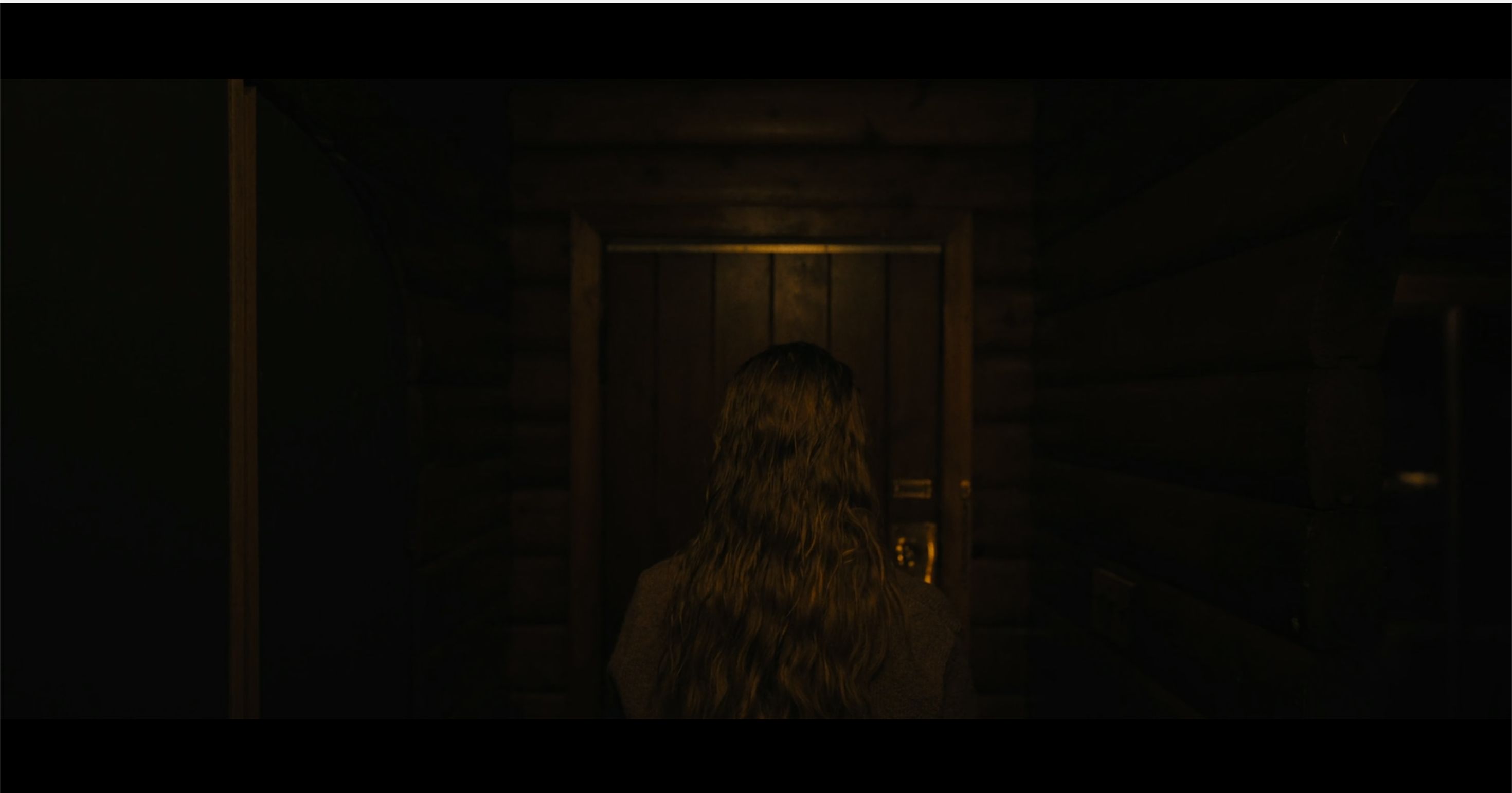

There is an entirely internet phenomenon that has entered the imagination and absorbed, sometimes without wanting it, by us postmedia users. It is that of liminal spaces, liminal spacesby definition those images of the network, often Y2K aestheticwhich present streets of the American suburbs, uninhabited houses, desolate offices, endless garages of any shopping center, corridors. The impression is that of a threshold, of a passage from places familiar to us towards unknown, disturbing, parallel dimensions. Oz Perkins' new horror film Longlegsseems to dialogue precisely with these imaginaries.

Among the most anticipated films of 2024 – thanks to an impeccable communication strategy – the film stars Nicolas Cage as a serial killer and Maika Monroe, detective Lee Harker on his trail. A step back to the 70s: Oregon, a little girl meets a disturbing figure who we already know is the killer we were waiting for, the mask is exhibited in what is perhaps a disguise or simply the his type. Today, in Bill Clinton's nineties, that little girl is an adult detective, she has a gift: she is a kind of medium who can perceive things, she has a plus. Maika Monroe is still one final girl come in It Follows; there in a role that reflected on the canonized figure in the golden age of horror, here in a doppelganger of Kubriackian memory.

A story of family massacres reemerges from the past, perhaps driven by a serial killer who, as per the manual, sends letters in encrypted code, echoing the most mentioned of serial killers, Zodiac. Here, however, the code is decrypted by agent Lee Harker who immediately appears to us as a character linked to the terrible murderer. But how? Why?

Perkins' geometric, rigorous film scares and sometimes escapes an impeccable development, but on the other hand, why look for a rational explanation at all costs? Horror is the child of the fantastic and in many cases logic is missing in favor of the visual experience, of the fear that the spectator seeks. Longlegs fully satisfies this request. The 4:3 sequences in which the figure of Dale Kobble is cut, the cropped shots, the claustrophobic space of the choice ofaspect ratioincrease the unnerving effect.

A serial killer who does not physically kill, the embodiment of Evil, a demon who physically destroys the American dream of the perfect family, acting through a vicarious, reliable and façade figure. Religion as a disguise, again. From the serial killer we expect meticulousness and rational explanations of the reasons for the atrocities he committed and, instead, Perkins removes the actions of his monster from any logic. Simone Sauza writes in his book Everything was ash. On serial killing (Nottetempo, 2022), when the author tries to deconstruct the common belief about the existence at all costs of a biographical accident and a trauma that motivate the serial murderer: «Hence my insistence on the deconstruction of the trauma . Even before any catastrophic event in personal biography, it must be recognized that the original trauma precedes everything, even birth; the fracture is in subjectivity itself, inscribed in the material configuration that everyone is, therefore latent in that evolution of matter which at a certain point in cosmic history became alive by referring to itself as an ego. […] This original trauma, which with an invisible mark, touched the flesh, is the possible condition of every trauma. In the serial killer's homicidal experience this original remainder emerges and destabilizes their experience; but it is a possibility that, in different forms, concerns everyone.”

Kobble is the embodiment of that cosmic trauma in that enigmatic body, living in the basement, that lies beneath the surface of the world. Longlegs it is, to simplify, a horror and a detective story that subverts every rule of the detective story, as it leaves the viewer with the ambiguity between rational and irrational, earthly things and supernatural things. A distant film, but very similar Sombre by Philippe Grandrieux who, already from the title (in Italian dark), takes us into the story of a serial murderer whose motivation for his terrible acts seems attributable to the intrinsic, profound, cosmogonic evil of the world.

So, perhaps, those desolate streets, those liminal spacesthose spaces as empty as they are frightening, which return several times in Perkins' film, are to the area in transition between what we can explain and the uncanny, the unfathomable that sometimes hides behind a family tragedy, the ones to which the news has accustomed us and whose reason often remains unknown. It is evil for evil and from evil. Lee, Danny Torrance's adult double, carries the burden of sensing it, feeling it, and living with it. Those thresholds at which he looks before the tragedy, those doors where he is often framed are nothing other than the point between the visible and oblivion, between rationality and incomprehensible horror. And against any consolatory search to explain evil to us, Longlegs it places us face to face with the void.