Exhibition in Paris –

The Guimet Museum offers “Ming Gold”. A baroque China

From the 14th to the 17th century, goldsmiths created spidery works to satisfy the Court and wealthy merchants.

Published today at 9:21 a.m.

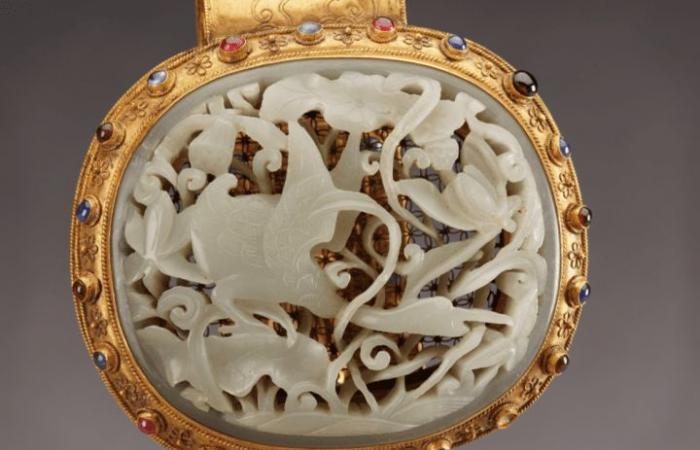

An art where emptiness often prevails over fullness.

Guimet Museum, Paris 2024.

Subscribe now and enjoy the audio playback feature.

BotTalk

China is in Paris. At least in the embassy. You may not have noticed it, the political context hardly lends itself to it, but we are currently experiencing the end of the “Franco-Chinese year of cultural tourism”. The only real waves that she has managed to produce are at the Guimet Museum, which Yannick Lintz now directs. The Parisian institution was accused in the press of having played the doormat by submitting to the desires of the “friendly” great power to erase all traces of dissidence. Anything that might have suggested independent Mongols would have been erased from the entire museum’s labels. Intimidation was much less successful at the Château de Nantes during the exhibition on the latter in 2023-2024. Breton resistance. I told you about it then.

Disconcerted audience

It must be said that Guimet was keen on his exhibition “The Gold of the Ming”, which was to constitute the major part of his season. It was about showing a quantity not only of jewelry, but of objects then collected by the imperial household and the elite of the kingdom. This presentation did indeed take place. It still lasts. But it has neither the media coverage nor the desired audience. Competition is always tough in the French capital. It also seems that visitors felt disconcerted by such baroque works. Even disheveled. They may indeed seem to border on kitsch. It remains to be seen on which side of the said limit…

A pair of applique vases, with jade plaques.

Guimet Museum, Paris 2024.

It is indeed a unique China that the museum offers not in its usual exhibition rooms in the basement, but in those on the first floor. The heart of historic Guimet, with the decor desired by its founder around 1900. There, squeezed into display cases, are around seventy pieces created between the end of the 14th century and the middle of the 17th century. Ming times. An indigenous dynasty. One of the few that the country experienced in its last imperial times. She came to power not without difficulty in 1368, putting an end to that of the Mongol Yuan that Marco Polo had known. It will disappear causing a long civil war to make way for the Qing in 1644. Manchus, in other words foreigners. The latter will remain authoritarian on the throne until 1911.

A golden scepter, here again with carved jade.

Guimet Museum, Paris 2024.

During their splendor, which corresponded to the construction of the Forbidden City in Beijing (now capital) in the 15th century, the Ming developed goldsmithing. Gold and silver, with some precious stones. Note in passing that their sources of supply of precious metals were the same as for the Europeans. Sometimes through indirect routes, like Japan, the Chinese obtained them from the New World. They had a huge need for it both for their business and to create luxury products. Those in gold remained in principle reserved for the Court. Hence, as with us, sumptuary edicts establishing lists of prohibitions. As with us again, we had to constantly remind offenders of these. An infallible sign that the laws were in fact not being respected. The less noble nobility and the new merchant class wanted at all costs the same jewels as the imperial entourage.

The top of a pair of bobby pins.

Guimet Museum, Paris 2024.

Virtuoso goldsmiths then used all the techniques. For them, time apparently didn’t matter. Visitors to Guimet will, however, quickly note that, in these bobby pins such as decorative baskets or vases, emptiness often prevails over fullness. With a few exceptions, it was a matter of making as big as possible with little material. Hence the featherweights, noted in the bilingual French-English catalog. A large pin ending in tassels weighs around ten grams. The overdecorated baskets around 180. We are here very far from the heavy Western prehistoric torques, where we count walls in kilos. Hence a proliferation of tips. In her text, Monique Crick (who was the director of the Baur Museum in Geneva) explains hammering, embossing, cutting, granulation and watermarking.

A phoenix-shaped object. A symbol reserved for the elite of the Court.

Guimet Museum, Paris 2024.

All of the pieces come from the Quinjang Museum in Xi’an, in central China. One of the oldest cities in the country. It seems that they are all part of a Dong Bo Zhai collection, owned by a certain Peter Viem Kwok. The man signs a small introductory text in the accompanying book. But Guimet remains as opaque on his subject as the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party meeting in plenary session may seem to the layman. The French institution holds some pieces of goldwork representing other eras. Older. Their presence would have accompanied the journey well. The photos can be found in the catalog. But we don’t mix tea towels with napkins, even if they are of the highest luxury. So there are only ones here for the Ming and Xi’an. It’s an option. A bit restrictive in my opinion.

The presentation, a little cluttered in my opinion.

Going out to Paris.

The big disappointment actually comes from the very weak staging. The objects are poorly lit in ordinary display cases, where they appear somewhat crowded. They give the impression less of a treasure than of a stock of precious materials. The visitor therefore circles around these exceptional productions without measuring their real value. Their abundant wealth should have encouraged commissioners Hélène Gascuel and Arnaud Bertrand to a more measured deployment, as could have been easily achieved in the temporary spaces in the basement. Published by In Fine, the catalog appears very good. Very clear. Very complete. However, it should be a derivative product, and not the piece de resistance. To be honest, I don’t understand what could have happened with the French national museum. I also don’t know what our Chinese friends might have thought of it. But they unintentionally lost face a little.

Practical

“Ming gold”, Guimet Museum, 6, place d’Iéna, Paris, until January 13, 2025. Tel. 00331 56 52 54 33, website https://guimet.fr Open every day, except Tuesday, from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. No real need to book. Bilingual French English catalog published by In Fine, 216 pages

“Etienne Dumont’s week”

Every Friday, find the cultural news sketched by the famous journalist.

Other newsletters

Log in

Born in 1948, Etienne Dumont studied in Geneva which were of little use to him. Latin, Greek, law. A failed lawyer, he turned to journalism. Most often in the cultural sections, he worked from March 1974 to May 2013 at the “Tribune de Genève”, starting by talking about cinema. Then came fine arts and books. Other than that, as you can see, nothing to report.More info

Did you find an error? Please report it to us.