He was one of the favorites for this 2024 edition of the Prix Goncourt. The Franco-Algerian journalist and writer was chosen by the jury in the first round, receiving six votes, against two for Hélène Gaudy, one for Gaël Faye, winner of the Renaudotand one for Sandrine Collette, announced the president of the Académie Goncourt, the writer Philippe Claudel. In its press release, the Academy evokes “a book where lyricism competes with tragedy, and which gives voice to the suffering linked to a dark period in Algeria, that of women in particular. This novel shows how much literature, in its high freedom of auscultation of reality, its emotional density, traces alongside the historical story of a people, another path of memory.

The announcement of the result in Drouant and Fiona Moghaddam's report, including Kamel Daoud's reaction

2 min

With only three novels to his credit, Kamel Daoud was already a regular at the biggest French literary prize. His first novel, Meursault, counter-investigationa postcolonial rewriting of The Stranger by Camus, earned him a place as a finalist at the Goncourt 2014 and then the Goncourt prize for the first novel in 2015.

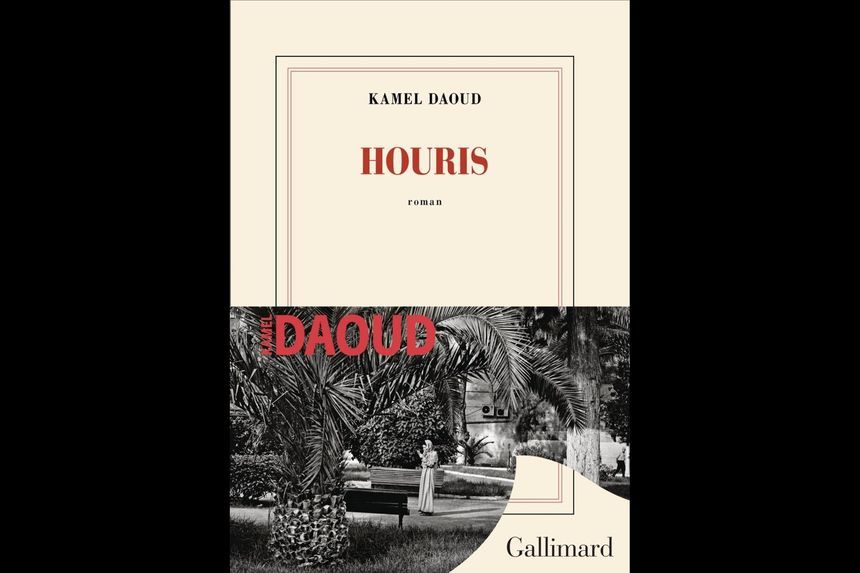

A decade later, it is with this 400-page novel, Hourispublished by Gallimard, that the Algerian writer and journalist, aged 54, was crowned. The work is intended to be a historical testimony, almost a fictional counter-investigation, of the civil war which fractured Algeria during the 1990s, pitting the government against various Islamist groups.

A book subject to Algerian law for the subject it evokes, because, as the author writes in his novel, it prohibits any mention in a book of the bloody events of the “black decade”, the civil war. between power and Islamists between 1992 and 2002. Gallimard editions were also not authorized at the Algiers Book Fair, from November 6 to 16, 2024.

Middays of Culture Listen later

Lecture listen 27 min

A novel that opens with a “smile”

The narrator of this novel, which opens in 2018 in Oran, introduces herself, from the first lines, with her muteness and her “smile”. If she is mute it is because of this scar, this smile precisely, ” dark, red, throbbing like a disembowelment. You should never put your finger on it and always disinfect after touching it. The “smile” goes from one ear to the other, it is the mark of the knife, its cut in my flesh. A seventeen centimeter wound, stitched up.”

Aube, the narrator, has carried this wound since she was five years old, when Islamist katibas murdered her family and tried to slit their throats, during the Had Chekala massacre on December 31, 1999. It is “the long calligraphic signature of the murderer who [l]'didn't finish, due to lack of time' . Having become mute, her voice barely louder than a hoarse and inaudible breath, she tells her story and that of her country to her daughter, whom she carries in her womb, and, through her, to the reader: “It’s laborious to tell a story to a person who barely sees this country from behind their stomach,” Aube assures her daughter. “I try to explain to you and I appear to you, foggy, like a foreign language“.

Giving voice to the silence

Aube may be mute, but she is no less talkative, as the 400 pages of this novel clearly show. If she only speaks a little “outer language “, often assimilated to that of Islam, in which it is called Fajr, Aube has its own “inner tongue” the language of resistance, of the writer, in which the narrator and the author merge.

Through Aube's story, through his “smile”, Kamel Daoud denounces, above all, the silence which still surrounds today the dark decade which struck Algeria. Because from 1992 to 2002, the war which pitted the Algerian government and the National People's Army against various Islamist groups caused more than 200,000 deaths… before amnesty laws allowed more than 6,000 Islamists to leave the country. maquis and return to their homes, despite the abuses perpetrated. In the name of peace and national cohesion, traumas were kept silent, and an entire population lives unsaid. Kamel Daoud's book begins with an epigraph citing The Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation of the Algerian regime, which ensures that anyone “instrumentalizes the wounds of the national tragedy to undermine the institutions of the Algerian Republic” faces prison.

So the author of this novel made Aube, a young 26-year-old Algerian, the indelible trace of a buried past: “We can’t erase your story, it’s written about you” my mother kept telling me. “How proud this image made me! Me ? A book? Would my body represent a big notebook, full of secrets? A writing so that no one can forget what happened in ten years in Algeria? His scar, the cannula which adorns his neck, are the unsightly testimony, the proof of a war which no one wishes to remember and for which no monument has been erected, unlike the Algerian War of Independence. “Perhaps they suspect that, through the hole in my throat, it is the hundreds of thousands of dead from the Algerian civil war who are staring down at them.” thus assures Aube to her daughter, who will never be born…

Les Masterclasses Listen later

Lecture listen 58 min

Save the “houris”

Because, in parallel with the civil war of the 1990s, Kamel Daoud also points to an entire patriarchal system. In this story, Aube, pregnant, speaks to her pregnant child. She chose to have an abortion, despite the ban that this represents in Algeria. “Believe me, granddaughter, I want to prevent you from being involved in a story where you will be just a woman, barely more important than one of these sheep,” she assures him. In an incessantly repeated motif, the narrator has “her blue fish”, “her Houri”, which she does not “murders him [que] to save her”, of a “hell to go through when you are born a woman in this country”.

Strengthened by her stigmata, which paradoxically protect her by making her invisible, Aube is a figure of a strong woman, a symbol – almost too literal – of these women deprived of their voice in a society that does not want them. In Oran, she runs a hairdressing salon, a bastion where women can get ready, and defy, a little, the law – of the country as well as of God – by resisting the intimidation of the Imam whose mosque is located there. 'other side of the square. It is “a silent war between my houris and the houris of the imam opposite” between the ” virgins patched up” and those “that no one has ever seen.”

If the book is titled “Houris”, it is precisely because it is the term which designates, in the Muslim faith, the virgins who will reward the faithful in paradise. “How can I make my fat clients, prey to kitchen fires and detergents, subjected to menstrual cycles and the cries of childbirth, how to make them valid houris? Those that God describes in his Book where we, women, are at sentences cited” asks Aube.

An allegorical and political book

In this story divided into three large parts (“The Voice”, “The Labyrinth” and “The Knife”), Kamel Daoud sometimes confuses the reader, by dint of inserting stories from each other. Between temporal backs and forths and changes of narrator (the second part of the work gives the voice to a second character, Aïssa, a truck driver who finds in Aube and her “smile” the trace of a war which he desperately tries to resolve. prove the existence), we sometimes feel a little lost and the lyrical style, if it is powerful, perhaps drags on a little in length. Nevertheless, there remain striking allegories, which mark the reading.

It is difficult, however, to forget that the author of the novel is a journalist, having written the columns of the Quotidien d'Oran and Le Point, as his subject is so political. With Houris, he delivers a counter-investigation fiction, pointing out the wanderings of the Algerian government, the failings of Algerian society towards women and the worrying place of Islam (the author makes the “prophets” and their “sheep” a of its leitmotifs).

These positions are not that surprising, given Daoud's background. His criticism of Islam, notably in the show We are not in bed in 2014, had already caused him to be the target of a fatwa by a Salafist imam.

With this new novel, Kamel Daoud has this time taken doubly risks, not only by calling into question the place that Islam gives to women, but also by defying the prohibitions of the Algerian government and the laws preventing the discussion of the decade black. Positions which also caused its publisher, Gallimard, to be excluded from the Algiers book fair last November.