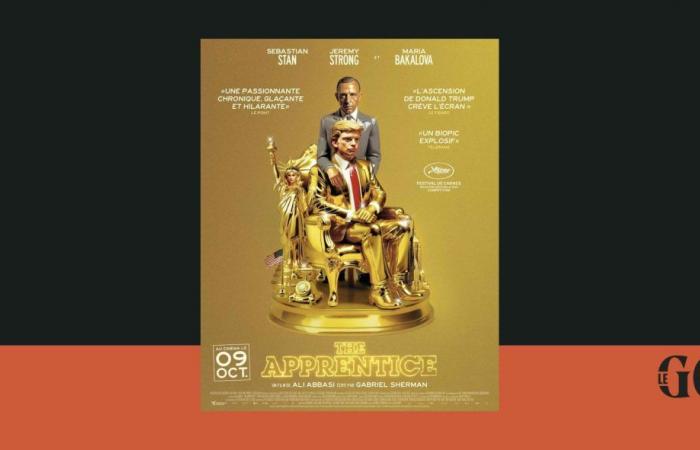

Ali Abbasi, Gabriel Sherman, The Apprenice

The making of the film The Apprenticereleased in France on October 9 and in the United States on the 11th, is in itself at least as incredible as its subject: who could have imagined a few years ago that the first biographical film on Donald Trump would be directed by a director, Ali Abbasi, born in Iran – and whose visit to the United States for the film was blocked for a time due to the “Muslim Ban” put in place in January 2017 by Trump –, would have been co-financed by the son-in-law of a billionaire and campaign contributor to ex-president Dan Snyder, and would come out just four weeks before what is shaping up to be the closest election in recent U.S. history — and which could also be the last one in which Trump will participate.

The Apprentice is more a film about the relationship between Roy Cohn and Donald Trump than a biopic about Trump himself. The scenario effectively leaves no doubt as to Gabriel Sherman’s declared desire to depoliticize as much as possible a film whose mere announcement of the release was enough to trigger a formal notice from the ex-president’s lawyers, as well as threats of his campaign against Sherman and the American distributors.

The period of the film, which extends from 1973 at the time of the first meeting between the two men until 1986, the date of Roy Cohn’s death, stops just before the first beginnings of Donald Trump’s political career. It was in 1987 that he denounced in a paid column published in three major newspapers in the country (the New York Timesthe Washington Post and the Boston Globe) the alleged abuses of the United States’ partners (Japan, Saudi Arabia “and others”), who would benefit from the protection of their interests by Washington without paying anything in return. It was at the same time, at the end of 1987, that Trump became a “public figure” and gradually detached himself from his image as a real estate developer by participating in Larry King’s show on CNN, then by organizing a first rally at the Rotary Club of Portsmouth in October 1987. A few days later, he published The Art of the Dealhis first book — written entirely by Tony Schwartz — describing his daily life and retracing his journey.

Sherman wanted to depict the origins of the Trump software on screen rather than Trump himself. The film is well documented and happily draws on the details distilled since the 1980s in several landmark books, notably the first biography of Trump, published by Jerome Tuccille in 1985, and his description of the clothing style of the young real estate developer, proudly displaying burgundy suits, embroidered shirts and imitating his father by wearing cufflinks engraved with “DJT”. The latter were also, like those of his father, matched to the personalized plate of his Cadillac, driven by a chauffeur through the streets of Queens and Manhattan. One of the film’s iconic scenes is taken from the pages of Lost Tycoonwritten by Harry Hurt III (1993), while the psychological traits of the character resonate with the family portrait drawn by the ex-president’s niece, Mary Trump, in Too Much and Never Enough (2020).

The spectator moves alongside the young promoter – mainly known in the early 1970s for being the son of Fred Trump – in the lounges of the “Club”, a restaurant reserved for members where he meets Roy Cohn – then a formidable lawyer known for his role as advisor to Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s and in the Rosenberg affair — in the dining room of his family’s Jamaica Estates home as well as on the cobblestones of 42nd Street, where Trump’s career took off after his renovation of the Commodore Hotel, now called the Hyatt Grand Central. Although it was not filmed in New York but in Toronto, the 1970s-style grain and overall aesthetic evoke more Taxi Driver by Martin Scorsese that the boardroom of the Trump Tower, scene of the famous “you are fired” uttered by Trump in the reality TV show The Apprentice thirty years later.

That was the risk in choosing a subject like Trump, seen and re-watched thousands of times on television and who seems to have constantly occupied the news feeds for nine years. In order not to appear caricatured, Abbasi should not fall into the line that could have placed the viewer in a form of Trumpian maelstrom, entering the room after having received a notification push reading “Trump said XXX about immigrants,” watching a near-copy of Trump on the big screen before leaving the room to read on his phone what he had called Kamala Harris over the previous two hours.

If he is rigorous, The Apprentice nonetheless remains a work of fiction. One of the few criticisms that we could make of Sherman is that he perhaps wanted to distance himself too much from Trump himself, who seems more to be a spectator than an actor in his life during a good part of the film. His education, his life course, his family situation and even his personality are relegated to a supporting role which suggest that Trump is a creature almost devoid of free will, perfectly malleable and shaped by Roy Cohn, the mentor who would have alone pushes the ex-president into his “dark side”.

A few scenes aside – for example those showing Trump having his stomach liposuctioned, swallowing methamphetamine pills to lose weight or having part of his head “scalped” to hide his baldness – Trump would probably appreciate The Apprentice. The young promoter, a bit of a dandy, stands out for his aggressiveness, his business intuition, his charm and his healthy lifestyle – no alcohol, tobacco or drugs (at least consciously). The lessons taught by Roy Cohn, “never admit being wrong”, “deny everything, admit nothing”, “attack, attack, attack” and their gradual implementation by Trump constitute the strength of the film.

The Apprentice is the story of a transition. Unlike most recent biopics about living figures — Priscillaprobably A Complete Unknown… —, the film does not end with the final version of Trump. If he had already become known for his transactional style, his proximity to dictators, his sexism as well as his aversion to any form of truth, Sherman could not have predicted in 2017, when finalizing the script, that Trump would try to defraud to get re-elected or his role played on January 6, 2021. The Apprentice thus depicts an intermediate form of Trump, who still had some contact with reality. If we wanted to follow through on the logic set in motion by Abbasi, we would need a second part to try to dissect the new form that emerged after the 2016 election. Without a doubt, we would go far beyond all the maxims by Roy Cohn.