(Bloomberg) — Twenty one years ago, Clare Lombardelli left the Bank of England as a junior macro-economist to pursue a career at the UK Treasury. She returns Monday as deputy governor for monetary policy, second-in-command behind Governor Andrew Bailey, at what could scarcely be a more critical juncture.

Market prices suggest there is 50-50 chance that interest rates will be cut for the first time since the pandemic on Aug. 1. Lombardelli, who replaces Ben Broadbent as the bank’s most senior economist but has never before set monetary policy, may end up holding the swing vote on the nine-strong rate-setting committee.

It will be a far cry from her Treasury career, where she rose to chief economic adviser, and more lately as chief economist at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. But the rate decision will just be the start. The 45 year old arrives at the bank to a bulging in-tray.

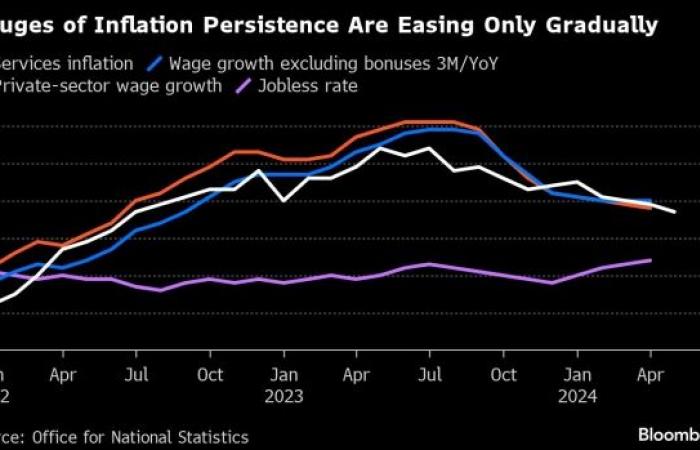

In her first 30 days, she will lead the inflation and growth forecasts for the August Monetary Policy Committee vote and have to decide whether to stick with the “prevailing consensus” left by Broadbent or come to new “judgments on topics like inflation persistence or the sensitivity of spending to interest rates,” said Richard Barwell, head of macro research at BNP Paribas Asset Management.

There’s few signs about how she might act, and Lombardelli did not comment for this article. In May, remarks she made in testimony to Parliament marked her out as a possible hawk, resistant to cutting rates, but she told lawmakers “it clearly is the case that that will be the direction of travel.”

In her last job, at the OECD, the forecasts she led in May “assumed” the BOE will cut rates a quarter point to 5% in “the third quarter” of 2024 and reduce them to 3.75% by the end of next year.

After the August rate decision and forecast, she will have to decide whether to support the BOE’s quantitative tightening program. The assets bought between 2009 and 2021, which peaked at £895 billion ($1.1 trillion), are being unwound but the BOE is unique among major central banks in conducting active sales rather than just letting the bonds mature and roll off.

Active sales are a form of financial tightening, which works in opposition to rate cuts. Lawmakers have also raised concerns about the cost of the program, which is currently shouldering the taxpayer with almost £10 billion a year in extra debt interest. As a former Treasury official, Lombardelli will be acutely aware of the fiscal cost.

Beyond September, Lombardelli’s challenge gets even greater. She is in charge of the bank’s response to a review by former US Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke, who made a series of recommendations to improve the BOE’s forecasting, modeling and communication.

It will be a moment for Lombardelli to stamp her authority on the institution, a potential calling card to succeed Bailey when his term as governor finishes in 2028. “Can I assure you there is going to be a shake-up in response to Bernanke? Absolutely,” she told MPs in May. She promised to “look at radically reforming what we do.”

Her ascent to the top of the BOE is a far reach from her childhood in Stockport, a post-industrial town in Greater Manchester. After attending a local state-funded school she made it to Oxford University, where she studied politics, philosophy and economics, then did a masters in economics at the London School of Economics before joining the BOE in 2001.

Two years later she was poached by the Treasury. In government she worked for former Prime Minister David Cameron and Chancellors George Osborne and Philip Hammond, for whom she helped pull together forecasts for various different scenarios for the UK’s exit from the European Union.

One City economist who voted for Brexit described Lombardelli as a “leading light of Project Fear,” as all the scenarios were economically dreadful. Asked by MPs in May whether she stood by her 2018 analysis that the free trade deal similar to the one the UK ultimately chose would cost the UK 5% in lost GDP, she said: “Sure.”

A more difficult charge to answer is that she is a Treasury plant. In 2018, Lombardelli was elevated to chief economic adviser at the Treasury after Dave Ramsden was made BOE deputy governor for markets. In that role she proved indispensable to both Rishi Sunak, as a new Chancellor in the early days of the pandemic, and later Chancellor Jeremy Hunt.

When the role of chief economist at the influential OECD came up, Sunak and Hunt threw their political capital behind her. She started in May 2023, but in less than a year was heading back to the UK, to the irritation of the OECD.

The Treasury can now claim two of its own among the BOE’s four powerful deputy governors — Ramsden and Lombardelli. In addition, three of the MPC’s nine rate setters were selected by a panel led by Lombardelli, though the final decision in each case was for the Chancellor.

Having fought her way from state school to the highest echelons of the UK establishment, Lombardelli is quick to reject accusations that she will be part of the groupthink created by a “very close link between the Treasury and the Bank,” as John Baron, a Conservative member of Parliament’s Treasury Committee, put it.

“I am not like your average economist in lots of ways,” Lombardelli responded. “We all bring our personal experience to those decisions.”

(Corrects spelling of name in first paragraph)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.