Alabama has seen more of its residents die since 2020 than the number of newborns welcomed into the state’s families over that same period.

And while the state’s population has continued to grow each year due to migration into Alabama, it’s a worrisome statistic at a time when the state’s policy makers are already concerned about the number of Alabamians who are not working, and the ability of new industry to fill jobs.

“That can prove to be a real economic challenge,” said former State Sen. Greg Reed, who is advising Gov. Kay Ivey on workforce participation numbers.

To be fair, a declining birth rate isn’t a problem faced solely by Alabama. Demographers and statisticians are seeing birth numbers globally plummeting in developing countries, and the effects are already being felt in parts of Europe.

Last year, the world population passed the 8 billion mark, so it wouldn’t seem to be much of an issue right now. But according to research, the global fertility rate has more than halved over the past 75 years, when around five children were being born to each female in 1950.

That number was 2.2 children in 2021. More than half the countries of the world were below the population replacement level of 2.1 births per female, as of 2021.

Demographers say that nationally, deaths will overtake births in the U.S. by the year 2040.

But Alabama is already there. Dr. Nyesha Black, the director of demographics at the University of Alabama’s Center for Business and Economic Research, broke that news earlier this month, to the surprise of some, at the Alabama Economic Outlook Conference.

“People used to say in politics, ‘It’s the economy, stupid,’” Black said. “Now they can say, ‘It’s the demography, stupid.”

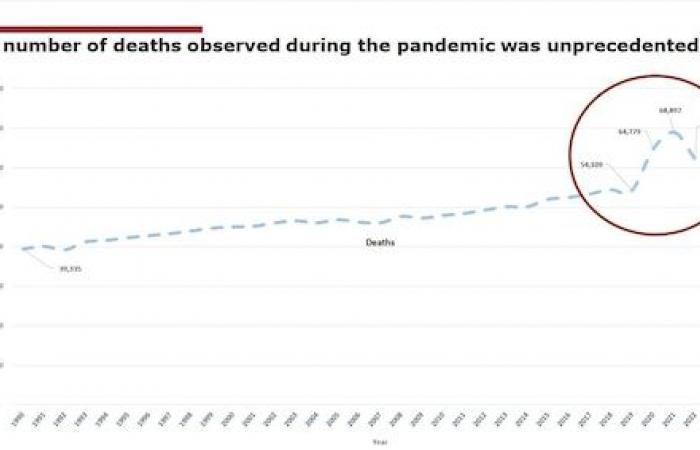

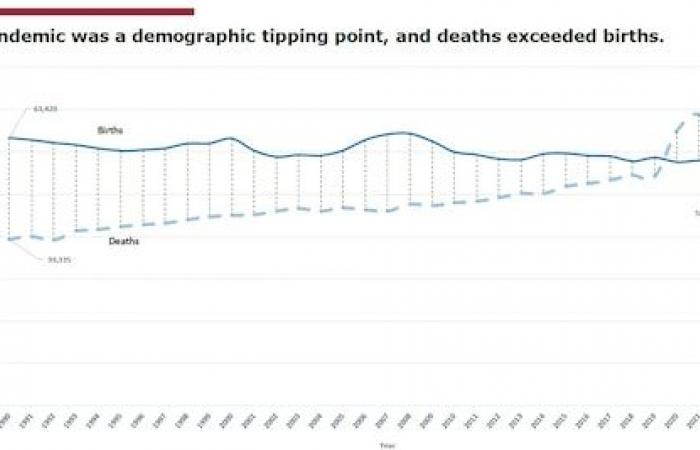

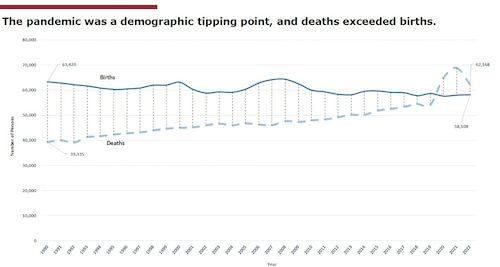

Deaths have exceeded births in Alabama since 2020.University of Alabama

To understand the problem, let’s go back to 1990, when Alabama saw more than 63,000 babies born, and recorded more than 39,000 deaths. That means the state’s population increased naturally by more than 24,000.

Births continued to rise as late as 2009, when Alabama had more than 64,000 births, a statistical high during that period. But deaths began to rise in the years after, with Alabama recording more than 50,000 deaths by 2013.

The turning point was 2020, the year of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Alabama had 57,643 births, but 64,779 deaths. The following year saw the trend continue, when the state saw almost 11,000 more people die than were born. The trend has continued every year since.

More people have died than have been born in Alabama since 2020.University of Alabama

“The pandemic was the tipping point,” Black said. “Before the pandemic, deaths were increasing about 1.1% a year. The flip (to more deaths than births) happened about five to 10 years earlier than it would have otherwise.”

Alabama’s population exceeded 5 million in 2020, with the census last year estimating 5,157,699 people calling the Yellowhammer State home. That means the state is making up the difference due to people moving in.

That number is also in keeping with a trend throughout the South, according to the Federal Reserve. The Southeast has grown 0.2 percentage points per year faster than the rest of the U.S. in economic performance numbers, including population. And since 2020, the region has doubled the number of people coming, largely due to quality of life and cost of living.

But the falling number of births is an issue that will have some effect on Alabama’s ability to attract industry in the future, former Commerce Secretary Greg Canfield said.

More people have died than have been born in Alabama since 2020.University of Alabama

“We’ve definitely got to get more people participating in the labor force,” Canfield said. “Our population is a little older. We’ve got a population over the age of 65 that I think is higher than most of our peer Southern states.”

-According to the census, Alabama’s percentage of the population over the age of 65 is 17.8%. A study by Lending Tree last year found that Alabama ranked third among the states where people were least likely to work past retirement age. Why? Because of the aforementioned low cost of living and quality of life.

Reed, along with other state officials, is working to get Alabama’s workforce numbers higher. Alabama’s labor force participation rate for November remained unchanged at 57.6%, lower than the national rate at 62.5% and among the lowest in the nation. The rate is the percentage of people in the working-age population who are employed or seeking jobs.

Black said the aging population may explain why that number is so low.

“You hear, ‘People just need to work, there are jobs out there,’” she said. “The reality though is that when those (workforce participation) numbers were good, you had a generation of baby boomers out there who were of working age engaged in the labor market. What is driving the declines is that our labor force is an aging population. About 70% of the decline in labor force participation is due to aging, not the economic behavior of people simply not working.”

Huntsville’s Mazda-Toyota plant in a 2021 aerial photo. (Marty Sellers | sellersphoto.com)

Companies have still had problems throughout the South satisfying labor needs. Seven years ago, when Mazda-Toyota decided to build its auto plant in Huntsville, it set an ambitious goal of filling 4,000 jobs. Ambitious, that is, given the number of expanding industries already locating in the Huntsville area and those labor participation numbers.

“It was an issue, and we knew it was going to be an issue,” Canfield said. “It took a lot of effort and collaboration with Mazda-Toyota, the state, our entire workforce programming, and locally. Huntsville really rose to the challenge.”

For the moment jobs are continuing to fill statewide. Companies locating South are seeing a larger number of retirees seeking jobs, while workers aged 25 to 54 are attached to gig economy jobs that offer greater time and office flexibility.

But you might ask – why is the birth rate declining? And why should we care if it is?

Let’s take the second question first: As stated above, a nation’s fertility rate has to be at least 2.1 children per woman to keep a population steady. According to the Centers for Disease Control, the birth rate has dropped in the U.S. to 1.6 births per woman. And that’s across many demographic categories: births are declining among teenagers, among the educated, lower and upper income, and in categories historically associated with higher birth rates, such as Hispanics, according to Pew Research.

There is some good news. Alabama was 49th among the states in the rate of decline in its birth rate from 2001 to 2020, checking in at a decline of 5.5%.

As to why fewer people are being born, there are several suggested reasons by researchers – women are marrying later in life, and couples are choosing career over childrearing in their 20s, meaning fewer children can be born. The cost of raising a child can be a factor for low-income families, while more affluent people may opt to spend their time and money on themselves. Fewer teenagers are reporting having sex. Alabama is no longer a primarily agrarian economy, where big families tend to split the farm work.

Some researchers have even blamed falling birth rates on the rise of social media. If people are online more, they contend, that’s less time they could be spending making other people.

But we should care about a declining birth rate for several reasons. As Politico reports, Social Security could face serious shortfalls if there aren’t enough workers paying into the system on a consistent basis. Fewer workers mean fewer people paying taxes, which could impact national and state budgets.

Beyond simply filling jobs, there’s also the potential effect on certain sectors of society. College enrollment of incoming freshmen at U.S. universities dropped by 5% last fall, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. It’s an issue that has garnered a name – the “demographic cliff.” Falling birth rates potentially mean smaller enrollments, less money coming in, and less qualified workers for high-quality jobs.

Fewer births became an issue during the 2024 presidential campaign, when Vice President J.D. Vance called a falling birth rate a “profoundly dangerous and destabilizing thing.”

In addition, relying more on older workers opens up other problems for industry. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, for example, points out that research is inconclusive as to whether age affects productivity. An aging workforce also means higher costs with insurance and other associated expenses.

But as Black pointed out, these numbers aren’t just numbers; they reflect individual choices that will have long-term social, political and economic implications in communities across Alabama for generations to come.

“Each of these numbers is a person,” she said.