Yellowstoneby many measures the most successful US TV series of recent years, concluded its six-year run in December. Writer-director Taylor Sheridan’s saga of Montana patriarch John Dutton, his feuding offspring and ruthless defence of their modern-day ranch has become an American phenomenon, with ratings sometimes topping 10mn, a figure rarely reached in the streaming era.

This is all the more remarkable as Yellowstone is a neo-Western, updating an unfashionable genre routinely declared dead since the 1970s. With its violently self-sufficient heroes, hopeless yearning for a familiar, inexorably fading cowboy past and Red State setting, it also parallels the Maga movement’s atavistic lure. Though Sheridan called for Trump’s impeachment in an unguarded 2017 interview, Yellowstone appealed first and most directly to conservative Americans otherwise underserved by prestige TV drama. In other words, he is making the Western great again.

Sheridan is fond of recalling the visceral distaste shown towards Yellowstone and its likely audience by an unnamed HBO executive who passed on the show. “[He] goes: ‘Look, it just feels so Middle America,’” Sheridan told The Hollywood Reporter in 2023. “We’re HBO, we’re avant-garde, we’re trendsetters. This feels like a step backwards. And frankly . . . I don’t think anyone should be living out there [in rural Montana]. It should be a park or something.”

Sheridan has disproved that prejudice. Though Yellowstone itself has now concluded, his cowboy cottage industry of personally scripted spin-offs, which began with the Old West prequel 1883continues undiminished. The second season of 1923with Harrison Ford and Helen Mirren leading an earlier era of Duttons, will arrive in February, and numerous further shows are promised.

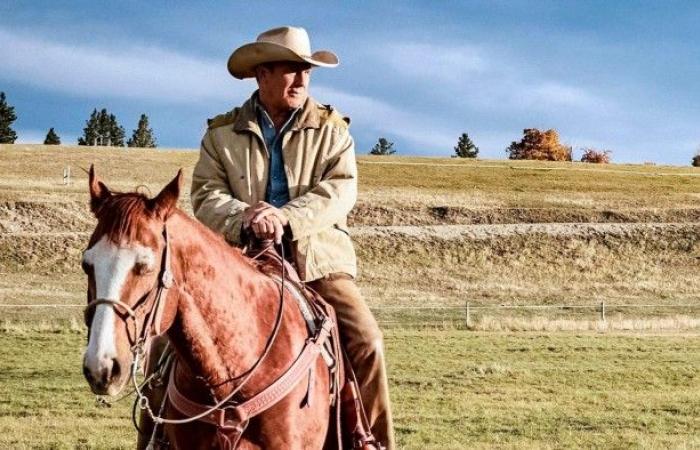

This is part of a wider Western revival. Kevin Costner, who starred in Yellowstone as John Dutton, has parlayed his success (and $38mn of his own money) into a long-planned Western cinema series, Horizonthough the first chapter faltered at the box office last summer. Showing the genre’s stubborn potency, Jane Campion and Martin Scorsese too have been lured west in recent years, for The Power of the Dog (2021) and Killers of the Flower Moon (2023) respectively.

Netflix, too, has joined the stampede. Last year’s Territory followed a modern Australian ranching dynasty competing over a vast Outback cattle station. Now, it is unveiling American Primevalset in 1850s Utah and Wyoming — lawless terrain warred over by Mormon militia, white settlers and Native American tribes.

“Yellowstone definitely helped [our show] get made,” says American Primeval director Pete Berg. “Taylor reminded the financiers and the audience that there’s an appetite for this genre. He didn’t reinvent it, he just did it really well, and showed people that there’s a reason why Westerns have existed as long as they have, a reason why people fighting to survive and build things with their blood and hands is appealing. That animal instinct is part of who we are.”

The Western at its most potent existed on the pregnant edge of American possibility: the frontier, a place of encroaching modernity and Native American extermination. Sheridan’s work insists that this edgeland endures. He made his name by writing a trilogy of what he calls “modern-day American frontier” films: Emily Blunt’s DEA agents tackling Mexican cartels in Sicario (2015); Jeff Bridges’ Texas Ranger hunting a bank robber trying to pay off his recession-hit farm in Hell or High Water (2016); and Jeremy Renner and Elizabeth Olsen investigating the rape and murder of Native Americans in Wind River (2017).

American Primeval designates its own, older savage frontier. Its Fort Bridger seems dug out of the mud: a precarious, filthy outpost with a shanty town of Native American tepees slumped at its edge. This American wasteland seems related to Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian (1985), with its feverish suspension in senseless violence along the 1850 Texas-Mexico border. American Primevaltoo, plunges into apocalyptic, pitiless conflict, seeming to suggest America was born — even cursed — in blood.

The young narrator of 1883Elsa Dutton (Isabel May), shares similar sentiments as her wagon train heads west, and elegant furniture and pianos are left scattered on the plain: “Here there can be no mistake, because here doesn’t care . . . If you are too weak, you will be eaten.” Yellowstone sees little changing today, as the Duttons’ enemies are dumped in a ravine long used for that purpose. “Wanna know how the West was won?” a cowboy spits. “The skeletons at the bottom of that canyon’s how.”

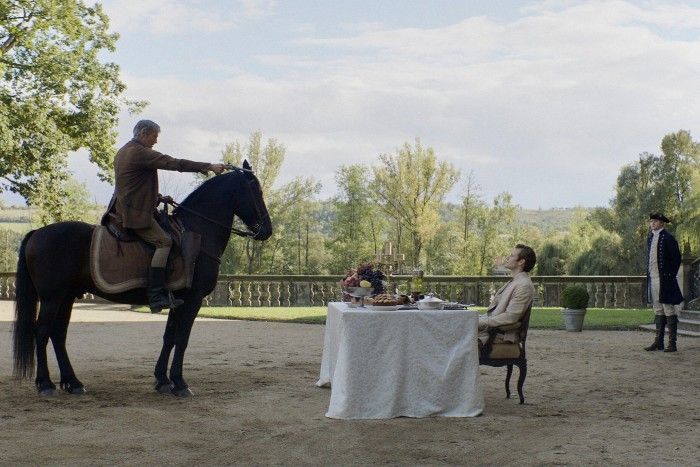

Today’s Western isn’t, though, uniquely the domain of white American heroes resembling John Wayne; its dramas of landowners and settlers, natives and colonisers have proved universal. The Promised Land (2023) finds Mads Mikkelsen stubbornly staking his claim on a harsh 18th-century Danish heath despite a local landowner who boils peasants alive, while Ivan Sen’s 2013 Australian neo-Western Mystery Road and 2018 TV series of the same name finds Indigenous detective Jay Swan (Aaron Pedersen) confronting often racist crimes in the baking Outback.

American actor Viggo Mortensen, whose upbringing was partly spent on horseback in the Argentine pampas, has quietly made a career of internationalist Westerns, such as 2014’s Far from Men. He wrote and directed last year’s lyrically humane The Dead Don’t Hurtalso starring as a Dane who settles with Vicky Krieps’s French-Canadian outside a venal Nevada town. “We tried to make a classic Western,” Mortensen says, “but with a lot of attention to the cultural diversity, the languages, what the West was really like. Staying with an ordinary but psychologically strong woman when my character goes to war; the two leads not having English as their first language — that’s quite different for a Western.”

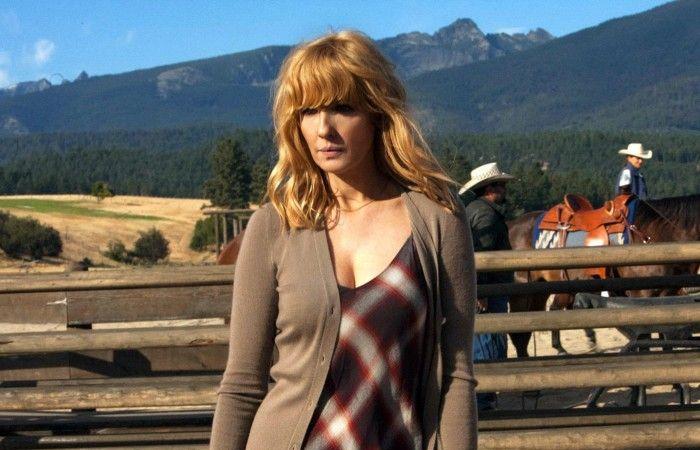

Yellowstonethough, re-establishes the Western as a timelessly American tale attuned to Trumpian times. Sheridan has fun satirising haplessly incapable incomers from Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York, which John Dutton’s ferocious daughter Beth (Kelly Reilly) calls “the failing cities of our nation”. And when John becomes Montana’s homespun governor, he pointedly disdains meeting the president (unnamed, but Joe Biden was in office at the time), growling, “I’ve got nothing to say to that idiot.”

Sheridan empathetically presents characters genuinely dismayed at modernity’s decadent ways, as when John discusses “the cancer of entitlement”, which seems a baffling affront to the show’s laconically self-sufficient cowboys. He also spends Yellowstone’s early seasons battling with the neighbouring reservation as Chief Rainwater (Gil Birmingham) plots to retake his ancestors’ territory from the ranch. And yet the show spends quality time on the reservation, observing Native American rappers and everyday life. It also includes the 1970s practice of sterilising reservation women requesting abortions, a crime to set beside Killers of the Flower Moon’s drugging and murder of oil-rich Osage Nation people a century before.

“They refer to it as . . . ‘the Republican show’ or ‘the Red State Game of Thrones,’ ” Sheridan told The Atlantic in 2022. “And I just sit back laughing . . . The show’s talking about the displacement of Native Americans and the way Native American women were treated and about corporate greed and the gentrification of the West, and land-grabbing. That’s a Red State show?”

Yellowstone’s great quality is its loving immersion in a fading cowboy life often incidental to classic Westerns, while retaining unfeasibly Old West quantities of fatal gunplay. Sheridan’s prodigious output has bought his own historic, traditional ranch, sharing John Dutton’s desire to conserve it. “Cowboy the fuck up,” one character chides, indicating the show’s ideal state for men and women.

As the dream of maintaining the Yellowstone ranch fades, the final episodes become a beautiful dying fall, lingering over cowboys roping and joking, and country bands playing as they wander the land contentedly, loss hanging over it all. The Duttons’ last stand ends in a satisfying denouement both neater and more nuanced than Maga visions could countenance. This is the rare cowboy story in which the natives win.

‘Yellowstone’ is on Paramount+, where season 2 of ‘1923’ begins on February 23. ‘American Primeval’ is on Netflix from January 9

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and Xand sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning