In a year of surprises – a posthumous fable from Gabriel García Márquez, a superhero collaboration between China Miéville and Keanu Reeves – the biggest news, as ever, was a new Sally Rooney novel. Interlude (Faber) landed in September: the story of two brothers mourning their father and negotiating relationships with each other and the women in their lives, it is a heartfelt examination of love, sex and grief. With one strand exploring the neurodiverse younger brother’s perspective, and a conflicted stream-of-consciousness for the older, it opens up a more fertile direction after 2021’s Beautiful World, Where Are You.

A new novel from Alan Hollinghurst is always an event, and in Our Evenings (Picador) he is at the top of his game, mapping Britain’s changing mores through the prisms of class, race, politics and sex in the memoir of a half-Burmese actor whose scholarship to public school catapults him into the world of privilege. Tender, elegiac and gorgeously attentive to detail, it’s a masterly evocation of the gay experience over the past half century.

There was a different approach to the big social novel from Andrew O’Hagan, whose Caledonian Road (Faber) is a rambunctious state-of-the-nation burlesque: centred on the downfall of a celebrity art historian, it burrows energetically through London’s layers, from aristocracy and cultural elite via Russian drug barons to the disenfranchised young. Meanwhile the provocative Choice by Neel Mukherjee (Atlantic) contrasts three separate narratives, ranging from climate anxiety among the metropolitan elite to poverty in rural India, to pose difficult questions about globalisation and morality.

Other notable returns included Sarah Perry, who in Enlightenment (Jonathan Cape) tracks patterns of unrequited love and cosmic wonder against the path of the Hale-Bopp comet, all done with her customary grace and lashings of atmosphere. Evie Wyld’s spiky, unconventional ghost story channelling family trauma and conflicted love, The Echoes (Cape), confirms her as a major talent; as does Charlotte Wood’s diary of a woman retreating to a convent, Stone Yard Devotional (Sceptre), which unshowily explores forgiveness, accountability and despair in the face of the world’s horrors.

Ingrid Persaud’s ensemble piece about a real-life Trinidadian gangster, The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh (Faber), is a triumph of voice, while Anita Desai’s Rosarita (Picador), her first novel in a decade, is a rewarding riddle of family inheritance and historical trauma. Fugitive Pieces author Anne Michaels also doesn’t publish often; Held (Bloomsbury), an elliptical meditation on war and love, illuminates moments of human connection and transports the reader. Crooked Seeds by Karen Jennings (Holland House) stood out for its uncompromising vision: focusing on a bitter, broken white woman in post-apartheid South Africa, it fearlessly works difficult seams of entitlement and collective guilt.

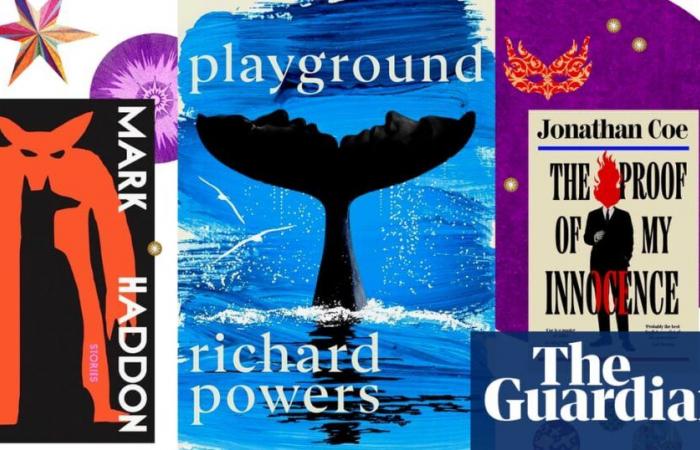

Two masters of comic fiction published new novels: You Are Here by David Nicholls (Sceptre) follows the tentative romance of a middle-aged odd couple hiking through the Lake District, struggling with emotional baggage as well as their rain-sodden rucksacks: it balances absurdity and sadness with apparently effortless ease. In The Proof of My Innocence (Viking), Jonathan Coe spins a cosy crime spoof around the rise and rapid fall of Liz Truss; this playful, metafictional romp is enormous fun.

In the summer, Taffy Brodesser-Akner followed up her landmark debut Fleishman Is in Trouble with a chronicle of intergenerational American wealth and trauma, Long Island Compromise (Wildfire); while for absorbing beach reads, Marina Kemp’s elegantly written saga of a family in thrall to the novelist patriarch at its helm, The Unwilding (4th Estate), was hard to beat.

Miranda July brought comic zest to her autofictional tale of midlife doubts and desires, All Fours (Canongate), in which an artist takes a bizarre road trip to the heart of her own shifting identity. This witty, honest, no-holds-barred and determinedly offbeat novel explores women’s impulses towards creativity and self-expression.

It was a strong year for American fiction all round, from the widescreen realism of Richard Powers’s Playground (Hutchinson Heinemann), an epic celebration of marine life and a meditation on progress and AI, to Percival Everett’s magisterial satire James (Mantle), an essential rewrite of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, and Rachel Kushner’s breathtaking spy caper Creation Lake (Cape), which unpacks how we construct politics, history and our own selves. I was on this year’s Booker prize judging panel, which spotlit all three, but in the end we gave the prize to a novel published last winter: Samantha Harvey’s gorgeously wrought Orbital (Vintage), a new and profound perspective on the Earth in all its beauty and fragility and a vital read in an age of environmental degradation and territorial violence.

Irish novels dominated in 2023; this year, the shelves were full of Irish sequels, with satisfying follow-ups from Colm Tóibín in Long Island (Picador), Roddy Doyle in The Women Behind the Door (Cape), and Donal Ryan in Heart, Be at Peace (Doubleday). Elsewhere, Tommy Orange returned to the characters of his debut in Wandering Stars (Harvill Secker), bringing both impressive historical sweep and touching domestic intimacy to an account of a Native American family over two centuries. Pat Barker concluded her Women of Troy trilogy with The Voyage Home (Hamish Hamilton), another sparkily down-to-earth take on Greek myth, which dramatises the bloody reckoning between Agamemnon and Clytemnestra. And Ali Smith began a new project: Gliff (Hamish Hamilton), the first in a duology, playfully charts two children’s resistance to a state dystopia of surveillance and control.

It’s been an excellent year for debut novels, many of them fizzing with energy and formal innovation. The Lodgers (Granta) is poet Holly Pester’s sideways take on housing precarity, exploring emotional unrootedness through one woman’s sublet, while in The Night Alphabet (Riverrun) another poet, Joelle Taylor, brings extraordinary linguistic inventiveness to a tale of tattoo artists and violence against women. The uncategorisable Spent Light by Lara Pawson (CB Editions), a hybrid of fiction and life writing, thrillingly traces the webs of connection that resonate outwards from household objects and everyday life, to expose the dark underbelly of our globalised world. Rita Bullwinkel’s quirky portrait of teenage female boxers, Headshot (Daunt), is itself organised as a tournament, while Anna Fitzgerald’s Girl in the Making (Sandycove) is told through the eyes of a young girl, growing older with each chapter. The irresistible narrator of Only Here, Only Now by Tom Newlands (Orion), a Scottish teen in a deprived 90s estate, expresses her ADHD through a glorious riot of prose. And in Anne Hawk’s The Pages of the Sea (Weatherglass), a girl is left with relatives on a Caribbean island when her mother sails to England to find work: this fresh perspective on the Windrush generation uses dialect to convey the young child’s thoughts with vivid immediacy. Portraits at the Palace of Creativity and Wrecking by Han Smith (JM Originals), a dystopian coming-of-age fable, employs obfuscation and ambiguity to explore propaganda and dissidence.

I found The Borrowed Hills by Scott Preston (John Murray), a pitch-black western set amid the sheep farms of Cumbria, striking and powerful, while Colin Barrett’s Wild Houses (Cape), a darkly comic tale of claustrophobia and violence in a small Irish town, is as stellar as his feted short stories. Yael Van Der Wouden’s The Safekeep (Viking), which uncovers repression and queer desire in the post-Nazi era Netherlands, makes a dazzling hairpin turn two thirds of the way through. Going Home by Tom Lamont (Sceptre) is the gently comic, bittersweet story of a London man finding himself with responsibility for a two-year-old boy, in all his delightful, demanding, exhausting energy. Meanwhile, the invention and confidence of Ferdia Lennon’s Glorious Exploits (Fig Tree), which brings a modern Irish vernacular to Ancient Sicily, makes him a writer to watch.

Other historical highlights included Kevin Barry’s The Heart in Winter (Canongate), a Tarantino-esque doomed romance set in an 1890s American mining town, and Carys Davies’s Clear (Granta), a short and surprising novel about Highland clearances, solitude and language loss, which showcases her trademark intimacy and expansiveness. In short stories, Mark Haddon’s Dogs and Monsters (Chatto & Windus) moulds myths and fables into vivid new shapes, while Eliza Clark’s gleefully dark She’s Always Hungry (Faber) blends genres and busts taboos.

Finally, a recent publication that deserves the widest attention. Andrew Miller is known for acute and unnerving historical novels such as Pure and Ingenious Pain, but in The Land in Winter (Sceptre), a study of two young marriages during England’s 1962-3 Big Freeze, he may have written his best book yet. The shadows of madness, and of the second world war, extend into a world on the cusp of enormous social change. Miller conjures his characters and their times with a subtle brilliance that is not to be missed.