Russian dolls

“His life well symbolizes the twists and turns of the second part of the 20th century”. It is in these terms that Emmanuel Carrère summarized the chaotic existence of Edouard Limonov in his 2011 biography; a surprisingly concise sentence for a man who was in turn a writer, poet, exile, butler, dissident and creator of a political party.

No wonder Kirill Serebrennikov threw himself into adapting the book to capture all of its explosive dimension. It is clear that the filmmaker recognizes himself in this figure of chaos, which clearly reflects the attraction-repulsion of a large part of Russia for its Soviet heritage.

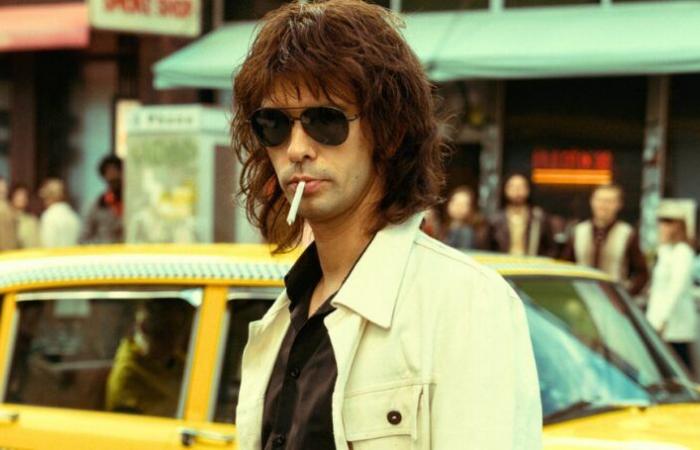

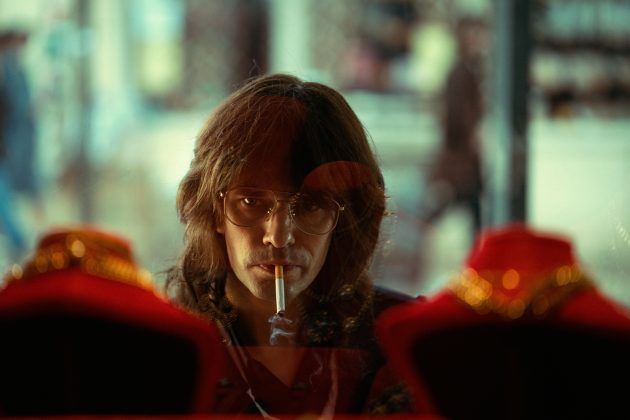

In fact, the director of Leto indulges a little too much in the sulphurous dimension of his project, filled with nihilistic voice-overs and misanthropy. Serebrennikov takes the risk of making his character unsympathetic, and Ben Wishaw wonderfully supports the electric energy of this ball of contradictions (to the point that we forgive the slightly overdone accent).

The camera has the right tone to focus on the body of its protagonist, whose paradoxes and mood swings the interpreter highlights at every moment. More than the announced rock ballad, Limonov is above all a bipolar filma work of collage which constantly seeks breakage, the impossibility of fluidity. Even within overtly spectacular sequence shots, it is above all a question of a sinuous and heterogeneous mosaic, where people and years pass by during events which shake up the world (fabulous scene with virtuoso theatrical staging).

From gaucho to facho

It is this messy journey that fascinates Serebrennikovswitching from Ukraine in the 1960s to New York in the 1970s before returning to Europe in the 1980s, between Paris and a USSR at the end of its life. The result sometimes looks like a fictionalized Wikipedia entry, and at the same time, his character is all the more elusive. His exile in the United States is more out of boredom than out of real conviction, and his polemical writing seems to reflect his deep desire for success.

If the whole is regularly intoxicating in its translation of a fantasized hedonism, it must be recognized that the author of Petrov's Fever doesn't really follow through on its concept. By focusing mainly on Limonov's New York period, he passes a little quickly on his return to Russia and the founding of the National Bolshevik Party in 1993, a precursor of the neo-fascism which has plagued the country since. It will also be necessary to settle for a final card so that his support for Vladimir Putin in 2014 regarding the annexation of Crimea is mentioned.

How do you go from dandy punk to crypto-fascist? Kirill Serebrennikov only touches on the issue, although this restraint can be understood from an artistic point of view. Rather than interpreting the improbable itinerary of his weather vane intellectual, he sees this man of a thousand lives as a political catalyst, going from one extreme to the other with small impressionist touches.

In contact with this broken compass, the entire historical tension of the Eastern bloc emerges, between its hopes and its disillusionments. This ballad is perhaps first and foremost that of a 20th century which tried everything, experienced everything, before despairing in the face of policies that were constantly flouted and perverted. Seemingly, in the chaos of his narration and his stylistic effects, Serebrennikov makes each shot and each sequence the pieces of a puzzle to put together : that of the origins of a 21st century which no longer knows where to turn.