With funding from the National Science Foundation, a team of archaeologists from LSU

and the University of Texas at Tyler have excavated the earliest known ancient Maya

salt works in southern Belize, as reported in the journal Antiquity.

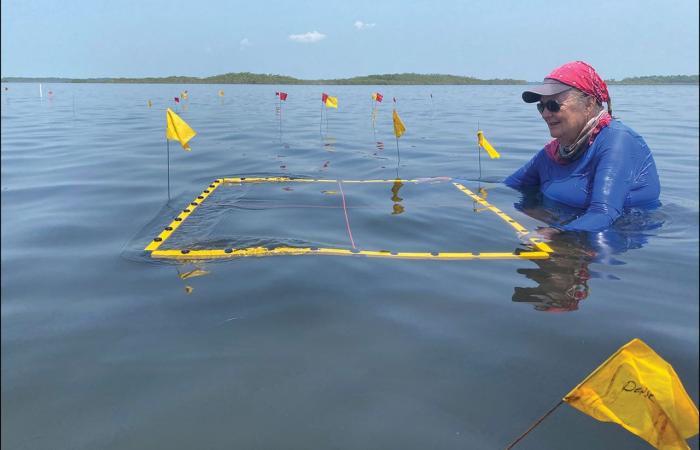

An excavation grid is put in place to mark an area of high-density pottery on the

sea floor.

– Credit: E.C. Sills

The team was led by LSU Alumni Professor Heather McKillop, who first discovered wooden

buildings preserved there below the sea floor, along with associated artifacts, and

the only ancient Maya wooden canoe paddle in 2004.

Her key collaborator, Assistant Professor Elizabeth Sills at the University of Texas

at Tyler, began working with McKillop as a master’s student and then as a doctoral

student at LSU.

Since their initial discovery of wood below the sea floor in Belize, the team has

uncovered an extensive pattern of sites that include “salt kitchens” for boiling seawater

in pots over a fire to make salt, residences for salt workers, and the remains of

other pole and thatch buildings.

All were remarkably well preserved in red mangrove peat in shallow coastal lagoons.

Since 2004, the LSU research team has mapped as many as 70 underwater sites, with

4,042 wooden posts marking the outlines of ancient buildings.

In 2023, the team returned to Belize to excavate a site called Jay-yi Nah, which curiously

lacked the broken pots so common at other salt works, while a few pottery sherds were

found.

“These resembled sherds from the nearby island site of Wild Cane Cay, which I had

previously excavated,” McKillop said. “So, I suggested to Sills that we survey Jay-yi

Nah again for posts and sea floor artifacts.”

After their excavations, McKillop stayed in a nearby town to study the artifacts from

Jay-yi Nah. As reported in Antiquity, the materials they found contrasted with those

from other nearby underwater sites, which had imported pottery, obsidian, and high-quality

chert, or flint.

“At first, this was perplexing,” McKillop said. “But a radiocarbon date on a post

we’d found at Jay-yi Na provided an Early Classic date, 250-600 AD, and solved the

mystery.”

Jay-yi Nah turned out to be much older than the other underwater sites. Through their

findings, the researchers learned Jay-yi Nah had developed as a local enterprise,

without the outside trade connections that developed later during the Late Classic

period (AD 650-800), when the inland Maya population reached its peak with a high

demand for salt—a basic biological necessity in short supply in the inland cities.

Jay-yi Nah had started as a small salt-making site, with ties to the nearby community

on Wild Cane Cay that also made salt during the Early Classic period. Abundant fish

bones preserved in anaerobic deposits at Wild Cane Cay suggest some salt was made

there for salting fish for later consumption or trade.

Next Step

LSU’s Scholarship First Agenda is helping achieve health, prosperity, and security

for Louisiana and the world.