Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

CNN

—

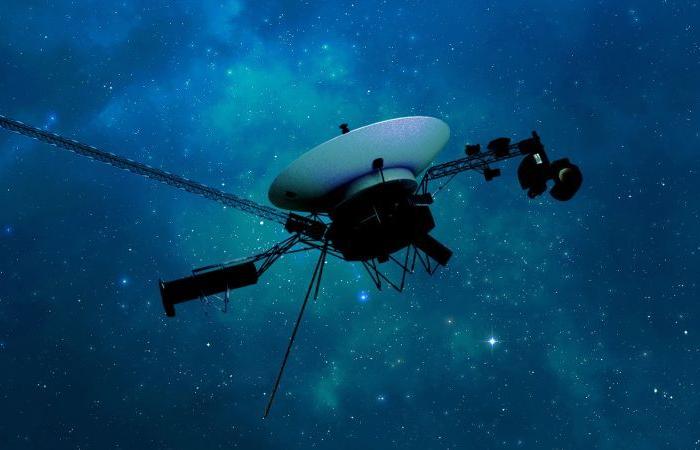

The 47-year-old Voyager 1 spacecraft is back in touch with NASA — but not out of the woods — after a technical issue caused a days-long communications blackout with the historic mission, which is billions of miles away in interstellar space.

Voyager 1 is now using a radio transmitter it hasn’t relied on since 1981 to stay in contact with its team on Earth while engineers work to understand what went wrong.

As the spacecraft, launched in September 1977, ages, the team has slowly turned off components to conserve power, allowing Voyager 1 to send back unique science data from 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) away.

The probe is the farthest spacecraft from Earth, operating beyond the heliosphere — the sun’s bubble of magnetic fields and particles that extends well beyond Pluto’s orbit — where its instruments directly sample interstellar space.

The new issue is one of several the aging vehicle has faced in recent months, but Voyager’s team keeps finding creative solutions so the storied explorer can zoom along on its cosmic journey through uncharted territory.

Occasionally, engineers send commands to Voyager 1 to turn on some of its heaters and warm components that have sustained radiation damage over the decades, said Bruce Waggoner, the Voyager mission assurance manager. The heat can help reverse the radiation damage, which degrades the performance of the spacecraft’s components, he said.

Messages are relayed to Voyager from mission control at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, through the agency’s Deep Space Network. The system of radio antennas on Earth helps the agency communicate with Voyager 1 and its twin probe, Voyager 2, as well as other spacecraft exploring our solar system.

Voyager 1 then sends back engineering data to show how it is responding to the commands. It takes about 23 hours for a message to travel one way.

But when a command to the heater was sent on October 16, something triggered the spacecraft’s autonomous fault protection system. If the spacecraft draws more power than it should, the fault protection system automatically shuts off systems that aren’t essential to conserve power.

The team discovered the latest issue when it couldn’t detect the spacecraft’s response signal through the Deep Space Network on October 18.

Voyager 1 has been using one of its two radio transmitters, called an X-band based on the frequency it utilizes, for decades. Meanwhile, the other transmitter, called the S-band, which uses a different frequency, hasn’t been employed since 1981 because its signal is much fainter than the X-band’s.

Engineers suspect the fault protection system lowered the rate at which data was being sent back from the transmitter, which changed the nature of the signal shared by Voyager 1 to the Deep Space Network monitors. The Voyager 1 team ultimately located the probe’s response later on October 18 by sifting through signals the Deep Space Network was receiving.

But on October 19, communication with Voyager 1 appeared to stop completely.

The team believes the fault protection system was additionally triggered two more times, which may have switched off the X-band transmitter and shifted the spacecraft to the S-band transmitter that uses less power, NASA said.

While Voyager 1’s team wasn’t sure that the faint S-band signal would be detectable due to the spacecraft’s distance from Earth, Deep Space Network engineers located it.

The team won’t send commands to Voyager 1 to turn on the X-band transmitter again until it deduces what triggered the fault protection system, which could take weeks. Engineers are being cautious because they want to determine whether there are any potential risks to turning on the X-band.

If the team can get the X-band transmitter working again, the device may be able to relay data that could reveal what happened, Waggoner said.

In the meantime, engineers sent a message to Voyager 1 on October 22 to check that the S-band transmitter was working and received confirmation on October 24. But it’s not a fix the team wants to rely on for too long.

“The S-band signal is too weak to use long term,” Waggoner said. “So far, the team has not been able to use it to get telemetry (information about the health and status of the spacecraft), let alone science data. But it allows us to at least send commands and make sure the spacecraft is still pointed at Earth.”

This transmitter switch is just one of several innovative hacks NASA has used to overcome communication challenges with the long-lived mission this year, including firing up old thrusters to keep Voyager 1’s antenna pointed at Earth and coming up with a solution for a computer glitch that silenced the probe’s stream of science data to Earth for months.