Huge quantities of Swiss potatoes end up in the trash due to strict quality requirements. Agroscope researchers show how this waste could be avoided.

Pascal Michel / ch media

This potato is good for consumption. Even less ugly, those with any defect never arrive at the store. Image: Rasbak / Wikimedia Commons

More than half of Swiss potatoes never make it from the field to the store. According to an ETH study, approximately 53% of conventional food tubers are eliminated throughout the production chain. For organic copies, this figure is even higher. The farmers directly bury part of the goods, the unsaleable potatoes thus become fertilizer. The rest is used to feed animals or create biogas.

A large proportion of Swiss potatoes end up this way because of the very strict quality requirements. They must in fact meet countless standards. Necessarily, potatoes should not be green or rotten, which could be dangerous for consumers.

On the other hand, other potatoes would be perfectly edible, but they are eaten away by wireworms and look unappetizing. It also happens that potatoes simply do not meet strict standards of size and beauty. On the retail side, we ensure that customers demand perfect products.

Looking at deformed potatoes in a different way

But in reality, retail customers have a bigger heart for shriveled or misshapen potatoes than you might think. This is what researchers from the federal research station Agroscope show in a new study.

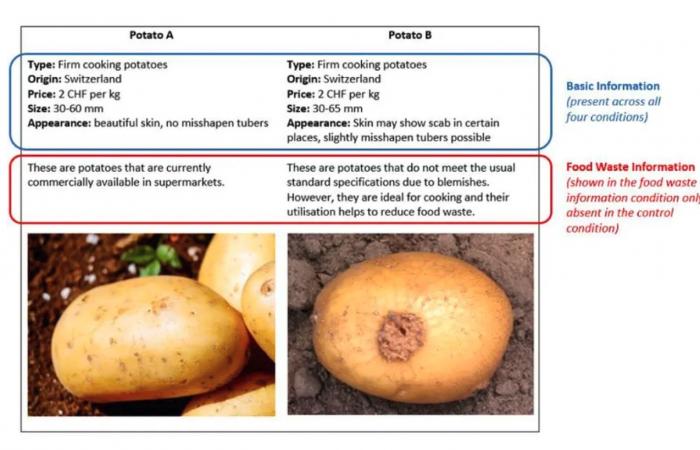

The scientists sought to find out how to encourage consumers to put atypical potatoes in their shopping baskets. In an online survey, they showed around 500 people a photo of a perfect firm-fleshed potato – and a less beautiful potato that had a defect. Which of the two is more popular?

In the first direct comparison, it is clearly the beautiful standardized potato that wins. If we imagine this situation in a supermarket, 71% of those questioned would turn to the potato that meets aesthetic standards, with only 29% choosing the alternative.

However, the appeal of the “ugly” potato increases markedly when consumers are provided with additional information. As soon as the respondents were informed that this potato could be eaten without problem and that its purchase helped avoid food waste, the acceptance rate increased to 46%.

Here’s what the test subjects saw.Image: agroscope

The sale of less attractive potatoes has “enormous potential” to limit losses, the researchers conclude on the basis of their results. To do this, merchants would not even need to lower the price of second-quality merchandise, but simply to better inform customers.

They should gradually put deformed vegetables on the shelves and familiarize consumers with this type of product, we can read in the study. There should also be “information campaigns which explain that these products remain edible”.

Curved carrots and purple garlic

Are marketers doing enough to convince their customers to eat foods that are not perfect? Migros sees no reason to carry out additional information campaigns. She notes that the Vegetable Producers’ Union adapted its standards last year. Since then, “products with minor beauty defects have also been available in isolation.” The M-Budget line has also always sold misshapen products. Thus, 4,000 tonnes of second category carrots and potatoes would have been sold in 2022.

Coop also underlines its commitment to the fight against food waste. The distributor sells twisted carrots or organic garlic with purple or brown discolorations under the Ünique label. This line saved 2,725 tonnes of fruit and vegetables last year, writes Coop at our request.

Agroscope study concludes that sales could be further increased by targeted information on the shelves. But for Coop, an information campaign on the shelves is not on the agenda at the moment, because it “already raises customer awareness of the topic of food waste through various means”. The distributor cites the example of products whose expiry date is approaching and which are sold with the sticker “Use instead of waste”.

The results of Agroscope researchers therefore remain theoretical. Scientists would certainly have liked Coop or Migros to reproduce them in practice. Because, as is often the case in sociological studies, there is a risk that those interviewed will not reveal their real intentions, but will deliver the socially desired response.

In other words, they know that food waste is a problem, and for this reason indicate that they would buy a misshapen potato if it would otherwise be thrown away. But when those same consumers are next in the store, they may act quite differently and settle for the perfect potato.

Migros, Coop, Aldi: more articles on supermarkets in Switzerland

Translated and adapted from German by Léa Krejci