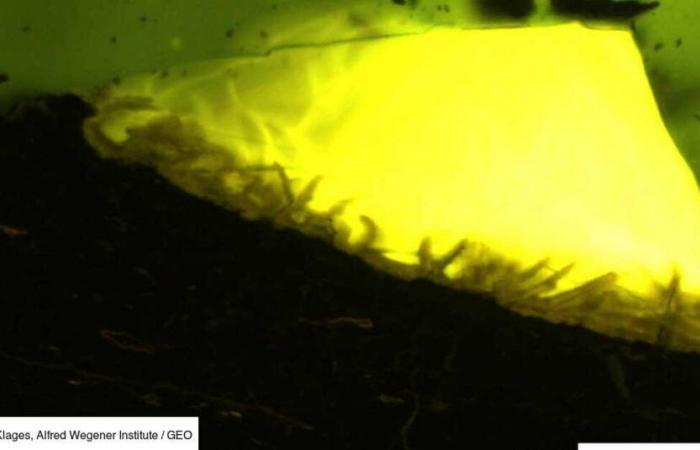

Its bright yellow glow is not revealed to just anyone – or rather, not under any conditions. First air-dried and then carefully cut into fragments 1 mm in diameter, the original material only finally revealed its fine amber inclusions under the magnifying glass of a reflected light microscope, with fluorescence.

The authors of an article published on November 12, 2024 in the journal Antarctic Science (Cambridge University Press) describe this incredible fossilized tree resin, identified in a sediment core taken during an expedition with the research icebreaker Polarstern in 2017, using drilling carried out to a depth of almost a thousand meters.

With an exact location of 73.57 degrees South, 107.09° West, “Pine Island amber”named in reference to the bay of Pine Island at the mouth of the Amundsen Sea where it was extracted, thus constitutes the “Southernmost amber discovery in the world” – and even the very first of its kind in Antarctica (press release from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Germany).

Trees facing insect attacks or fires

The fragments of amber brought to the surface thus make it possible to reconstruct a Cretaceous landscape, difficult to imagine for us who have always known a “white continent”: a marshy environment, rich in conifers, corresponding to a temperate rainforest.

“The analyzed amber fragments provide direct insight into the environmental conditions that prevailed in West Antarctica 90 million years ago”explains Johann P. Klages, first author of the study (press release).

This fascinating discovery also indicates in more detail how the forest we modeled in our study [Nature, 2020] could have worked.

Indeed, the type of resin at the origin of this amber seems to correspond to a strategy used by trees to seal the bark damaged by parasites or fires, thus forming a “chemical and physical barrier” protecting the plant from insect attacks and infections.

“Our goal now is to learn more about theecosystem of the forest – if it burned, if we can find traces of life embedded in the amber. This discovery allows us to travel into the past in an even more direct way.”concludes the Institute geologist.