(Vancouver) In addition to having long memories, these cunning birds hold grudges. But sometimes they take out their anger on the wrong person…

Published at 0:00

Thomas Fuller

The New York Times

That evening last July, the crows attacked Lisa Joyce, who tried to escape them by running down a Vancouver street.

Eight times they swooped at her, bouncing off her head and taking off again. Of all the people who attended the fireworks, only Lisa Joyce was targeted. “Why me? “, she wondered.

“I’m not a sissy and wild animals don’t make me nervous. But it was incessant and quite terrifying,” explains Mme Joyce. Last summer, she was targeted by crows so often that she changed her route to work.

Mme Joyce is not the only one to fear the wrath of the crows. CrowTrax, a website created eight years ago by Vancouverite Jim O’Leary, has received more than 8,000 reports of crow attacks in his leafy city where these corvids are quite numerous. And these conflictual encounters extend well beyond the region.

PHOTO ALANA PATERSON, THE NEW YORK TIMES

Known for their intelligence, crows can identify and memorize human faces, even in large crowds.

Neil Dave, who lives in Los Angeles, says crows attacked his house, slamming their beaks against his glass door so much that he feared it would break. According to Jim Ru of Brunswick, Maine, crows destroyed the windshield wipers of dozens of cars parked in front of his nursing home. Nothing stopped them.

Known for their intelligence, crows can imitate human language, use tools and gather for what resembles a funeral rite when one of their number dies. They can identify and memorize human faces, even in large crowds.

Furthermore, they are very resentful. When a group of crows considers a human to be dangerous, their anger can be strong and transmitted over more than one generation (the lifespan of a crow can reach around ten years).

A crow attack can sound like a horror movie, as in The Birds (The birds), d’Alfred Hitchcock.

PHOTOS ALANA PATERSON, THE NEW YORK TIMES

CrowTrax, a website created eight years ago by Jim O’Leary (left), who lives in Vancouver, has received more than 8,000 reports of crow attacks.

Typically, crow attacks occur in spring and early summer, when parents are watching over their young and defending their nests from possible intruders, experts say. But sometimes the reason is not so clear.

In July, when Lisa Joyce was being harassed by crows, she read on a Facebook group that many other women in her neighborhood were also being targeted and that they all had long blonde hair.

“I wondered if there was a link,” says M.me Joyce. Do they have a problem with someone with light hair? »

The Ogre and the Vice President

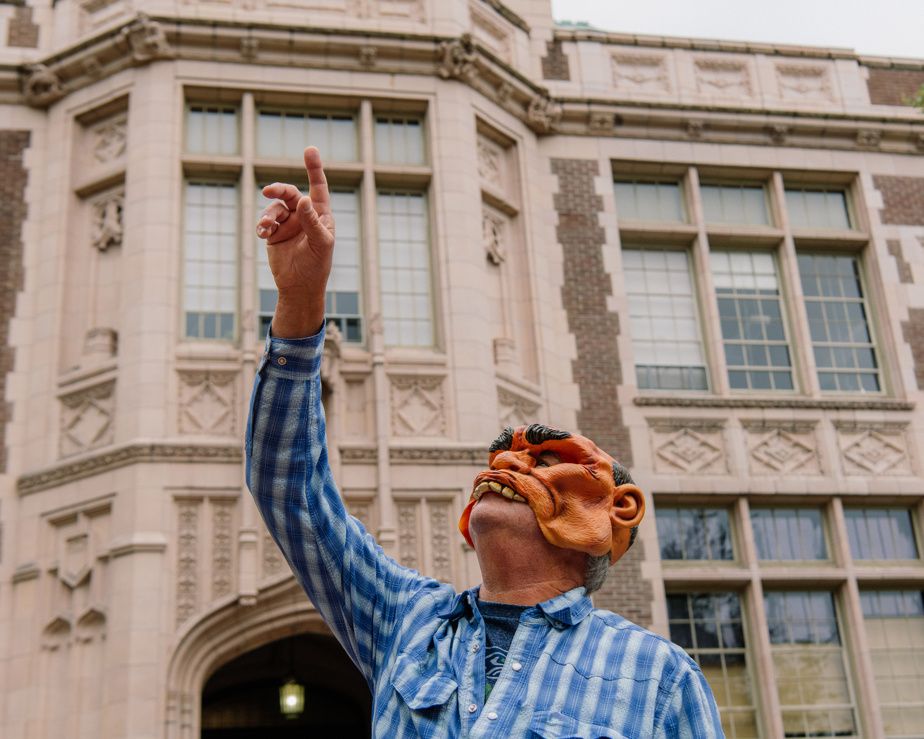

Last September, on a gray Sunday morning, a man wearing an ogre mask walked around the campus of the University of Washington in Seattle, attracting the looks of students astonished by a scene that looked like something out of a Halloween movie in low budget.

The masked man was John Marzluff, a professor who devoted his career to studying the interaction between man and crow. Mr. Marzluff has gained great respect for this intelligent bird, which he describes as a “flying monkey”, because of its abilities and its brain, which is large in relation to its size.

PHOTO ALANA PATERSON, THE NEW YORK TIMES

Professor John Marzluff, of the University of Washington in Seattle, wearing the ogre mask used in an experiment which demonstrated that crows could pass on information about people deemed hostile over more than one generation.

How many years does crows’ grudges last? Mr. Marzluff thinks he has found the answer: about 17 years.

It is based on an experiment he launched in 2006 on the university campus. Marzluff captured seven crows in a net while wearing an ogre mask. He quickly freed them, but the event traumatized the crows and other members of the group who had witnessed the capture.

To measure how long the crows would remember the event, Mr. Marzluff or his research assistants would periodically put on the ogre mask and walk around the campus, noting how many made aggressive cawing sounds.

The number of aggressive caws reached its peak seven years after the start of the experiment, when almost half of the crows encountered engaged in it.

Then, over the next decade, the number of resentful crows gradually declined, according to data collected by Mr. Marzluff, but not yet published.

During his walk last month, Mr. Marzluff noted in his notebook that he had encountered 16 crows: for the first time since the experiment began, they all ignored him.

PHOTO ALANA PATERSON, THE NEW YORK TIMES

Typically, crow attacks occur in spring and early summer.

To ensure that the crows really recognized the ogre, Professor John Marzluff included in the experiment that we make the same journey while wearing a “control mask”, that is to say another mask than that of the ogre (Mr. Marzluff had chosen a Halloween mask representing former vice-president Dick Cheney): in general, the crows did not react when they saw it.

Mistaken identity?

But sometimes this second mask also generated aggressive cawing, which shows that crows can make mistakes, says Marzluff. And that might explain what happened to Lisa Joyce and other blonde women in Vancouver.

Faced with the frightening prospect of being stalked for very long periods of time, victims of corvid attacks do not know how to react.

In Vancouver, there isn’t much to do. According to Angela Crampton, an environmental specialist with the municipal government, the city is proud of its large bird population, in part because it is an indicator of its environmental health.

“There’s a subculture of crow appreciation here,” she says.

PHOTO ALANA PATERSON, THE NEW YORK TIMES

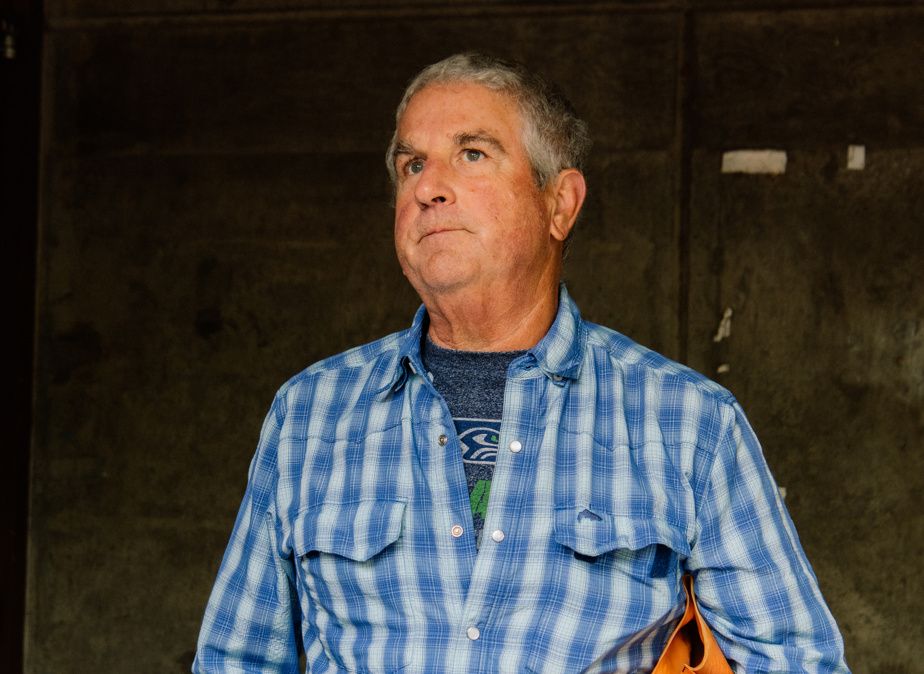

Professor John Marzluff

According to Mme Crampton, the Town advocates “coexistence,” and municipal workers do not remove crow nests or prune trees in an effort to reduce attacks.

Some people harassed by crows in Vancouver have found a way to make peace with them. Ten years ago, Jill Bennett was relentlessly attacked by crows every time she walked her dog. “I had never done anything to them,” says M.me Bennett.

Mme Bennett then carried peanuts in her purse, which she distributed to the crows on her walks. A pair of crows began to follow her, forming a sort of protective entourage.

PHOTO ALANA PATERSON, THE NEW YORK TIMES

Crows on a Vancouver beach, where they hunt small crustaceans and molluscs. The City of Vancouver does not take any action to reduce the crow population, even when they are aggressive.

Last summer, when a crow pounced on Mme Bennett, her two crow friends defended her and chased away the attacker.

Mme Bennett compares his peanut fee to mafia-style extortion. It’s like a protection racket, she says, the price to pay for not being attacked from the air.

“I am being taxed by the crows,” she said.

This article was published in the New York Times.

Read the original version (in English; subscription required)