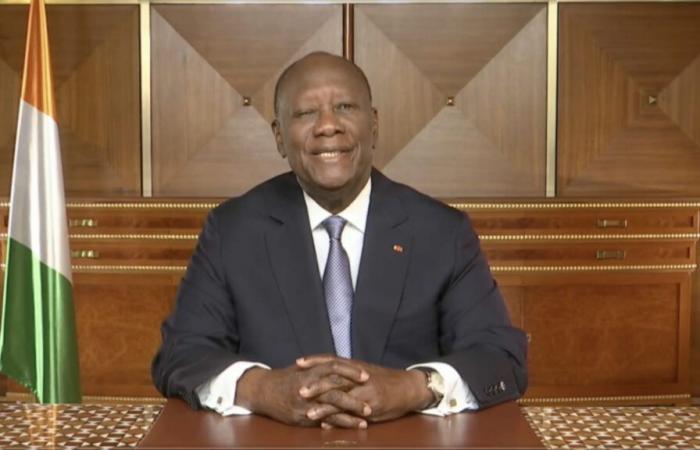

The flag of Côte d’Ivoire will soon be raised on the Port-Bouët military base. In his New Year’s greetings speech, President Alassane Ouattara announced the handover of the French military camp in Abidjan by the end of the month. The base will come under Ivorian command, and will be renamed “General Ouattara Thomas d’Aquin”, in homage to the first chief of staff of the country’s army. In terms of defense, Abidjan and Paris maintain a historic relationship, despite a particularly conflictual period during the presidency of Laurent Gbagbo. Arthur Banga is a researcher specializing in defense issues at the Félix-Houphouët-Boigny University in Abidjan. He answers questions from Sidy Yansané.

RFI: President Alassane Ouattara therefore announced the handover of the French military camp at Port-Bouët. On a purely practical level, what does this mean?

Arthur Banga: This means first of all that there will be a considerable reduction in the number of French soldiers in Côte d’Ivoire. They will go from around 400 to around a hundred and ultimately the camp will be commanded by the Ivorian army. From January, it will therefore clearly be an Ivorian camp.

The Ivorian head of state nevertheless clarified that this handover will take place within the next 30 days. So a very short deadline. Do you think this is feasible?

Yes, because it was prepared in advance. The announcement was made official in the Head of State’s speech to the Nation. But these are questions that have been debated for almost two years. The idea is therefore to abandon the principle of intervention to concentrate on questions of training, training and equipment.

It is also a page that is turning in the Franco-Ivorian relationship. The Port-Bouët camp was used for the French army’s Operation Licorne, which had a lasting impact on the Ivorians in the 2000s. What assessment do you draw from this military relationship between the two countries?

The big change today is that for the first time in the common military history of these two countries, we are moving away from the logic of foreign military intervention. French interventions on Ivorian territory, as we saw in 2002 and 2011, embody a model that must now be forgotten. That said, the results of Franco-Ivorian military cooperation are largely positive.

What aspects do you consider positive?

First, this cooperation allowed Côte d’Ivoire to maintain stability throughout the Cold War period when Soviet threats swept away certain regimes and even certain countries. We must not forget it. It allowed Côte d’Ivoire to set up its army and to be efficient at a certain moment in its history. In terms of weaknesses in the Abidjan-Paris relationship, we noted in 2002 the inability of the Ivorian army to be able to react, or the fact that the French army, through this idea of intervention, found itself on the front line. We saw it in 2002, in 2004 at the Ivoire hotel and in 2011. And precisely, today we are trying to get rid of these weaknesses to concentrate on the strengths of Franco-Ivorian military cooperation which is a relationship human, a real military camaraderie which was born between the soldiers of these two countries. The rise of armaments is also part of this cooperation.

After Senegal and Chad, this is the third announcement of a departure of French forces on African soil for the month of December alone. This is in line with the new military philosophy of Paris which wants a less visible presence, but while continuing its military cooperation. So how do you think this will work out?

We are in this new French vision, but we must not forget that this vision was mainly pushed by African public opinion, and even by African soldiers who want more independence, more freedom of maneuver. From now on, we are part of this new policy. With the Ivorian, Senegalese and Chadian cases, we have seen the various forms of military cooperation from France. In Chad, where the French army has intervened the most in Africa, French non-intervention in the face of the terrorist attacks which recently struck the country made this military presence useless in the eyes of the authorities because the logic of intervention was at the heart of military cooperation. In Senegal, it is above all the political logic of Ousmane Sonko and Bassirou Diomaye Faye which leads them to want zero foreign military presence. It is therefore something much more radical in their thinking, but which, through the democratic process which led to the coming to power of Diomaye Faye, makes it possible to build a new relationship in a more progressive way. In Ivory Coast, we have a tradition of openness with France. Except under the era of former President Laurent Gbagbo, the Ivorian authorities have always judged military cooperation with France well, including current President Alassane Ouattara. Because, despite his political and diplomatic victory during the post-electoral crisis of 2010-2011, the latter was able to gain power thanks to a military victory pushed by the French army.

And regarding this new articulation of the French army on the continent, what role can the International Academy for the Fight against Terrorism based in Jacqueville, near Abidjan, play?

This is the very desired model. We will place more emphasis on operational training, but also intellectual and judicial training. This model also favors multilateralism. France no longer wants to lock itself into bilateralism when it comes to military cooperation or even military intervention. This is why you see the American Flintlock military exercises taking place within the Academy. And all this under Ivorian command, let us remember.