Police came to pick up Ayshem Mamut from her home in northwest China.

Published yesterday at 10:15 p.m.

Edward Wong

The New York Times

They told him to pack his bags. She could have been taken to a prison or internment camp, like many other Chinese of the Muslim Uyghur ethnic group who have disappeared, sometimes for years.

But four days later, the 73-year-old was in Virginia for a Thanksgiving meal with two sons she hadn't seen in 20 years and four grandchildren she was seeing for the first time. times.

She talked, cried, over this meal of traditional Uyghur dishes: noodle soup, lamb stew, grilled chicken, salad and rice with chickpeas.

In late November, U.S. authorities revealed that China had freed three Americans, including an FBI informant, in exchange for two imprisoned Chinese spies and at least one other Chinese citizen. China has also quietly allowed Mme Mamut and two other Uyghurs, including an American citizen, to leave for the United States.

The Biden administration has not disclosed the part of the deal regarding the Uyghurs, which was revealed by the New York Times.

Waking up in the United States and seeing my family, especially my grandchildren, is a dream come true.

Ayshem Mamut

The Uyghurs' journey to freedom is the result of tireless efforts by their families and U.S. officials in the face of an increasingly authoritarian China.

Years of diplomatic efforts

American diplomats have discussed these cases privately for years in meetings with their Chinese counterparts. President Joe Biden mentioned Mme Mamut twice in meetings with Chinese President Xi Jinping.

PHOTO MORIAH RATNER, THE NEW YORK TIMES

Ayshem Mamut (center) with his sons Mamutjan Turkel (left) and Nury Turkel, in Alexandria, Virginia

China had banned Mme Mamut to leave the country because his eldest son, Nury Turkel, defended the rights of the Uyghurs.

“It’s amazing that she’s held on all these years,” said Mr. Turkel, 54, a former U.S. civil servant and researcher at the Hudson Institute.

Seeing his mother get off a Boeing 767 chartered by the US government at a military base in San Antonio, Texas, he went to greet her on the tarmac. He hugged her, then cried.

His resilience and ability to maintain hope despite disappointment is something that I personally cannot imagine as a free man.

Nury Turkel, from Ayshem Mamut

American authorities initially declined to comment on this article, but after its publication, the National Security Council issued this statement: “We are happy that Ayshem Mamut is reunited with her family. The Biden-Harris administration has consistently championed humanitarian causes, including that of the Uyghurs. »

Mr. Turkel and his family lived under Chinese rule for more than half a century. He was born in a re-education camp where his mother was detained in Kashgar, in 1970, during the cultural revolution. He arrived in the United States in 1995 as a graduate student and was granted asylum. His parents visited him in 2000, and again in 2004, when he earned his law degree from American University in Washington.

Advocating for the Uyghurs

Mr. Turkel has become a leading advocate for Uyghur rights. He documented cases of Uyghurs detained by the US military at Guantánamo, Cuba, during the post-9/11 wars. In 2009, his parents wanted to visit him again. When Chinese authorities denied them passports, they realized they were barred from leaving the country because of Mr. Turkel's activist activities. Mr. Turkel then pressured the Chinese government to let them travel.

Mr. Turkel's father, Ablikim Mömin, a retired professor, was able to travel to Türkiye to see his four sons in 2015 for two weeks. But not their mother.

Mr. Turkel pleaded his parents' cause to the Obama and Trump administrations. When President Donald Trump visited Beijing in 2017, he gave Chinese President Xi Jinping a list of people his administration wanted released. Mr. Turkel's parents were on this list, as was Ilham Tohti, a Uyghur professor sentenced to life in prison in 2014 for “separatism.”

In May 2020, House Speaker, Democrat Nancy Pelosi, appointed Mr. Turkel to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, where he served for four years.

In a virtual meeting in fall 2021, Mr. Turkel told Secretary of State Antony Blinken about his parents' plight.

PHOTO. CAROLYN KASTER, ARCHIVES ASSOCIATED PRESS

Mr. Turkel (center) taking the oath of office before his March 2023 appearance before a House Select Committee on Human Rights Abuse in China.

In December 2021, China announced sanctions against four U.S. officials on the Commission on Religious Freedom, including Mr. Turkel, in retaliation for sanctions imposed by the Biden administration on Chinese officials for abuses in Xinjiang.

Mr. Turkel spoke with Nicholas Burns, US Ambassador-designate to China, before his departure for Beijing. Mr. Burns then asked American diplomats to check on Mr. Turkel's parents in the city of Urumqi. “He made a personal commitment,” Mr. Turkel said.

Very close to his father's funeral

Mr. Turkel's father died in April 2022 at the age of 83. Mr. Turkel was on an official trip to Uzbekistan, a country a few hundred kilometers west of the Chinese border and the funeral. But he was unable to go there due to Chinese sanctions against him.

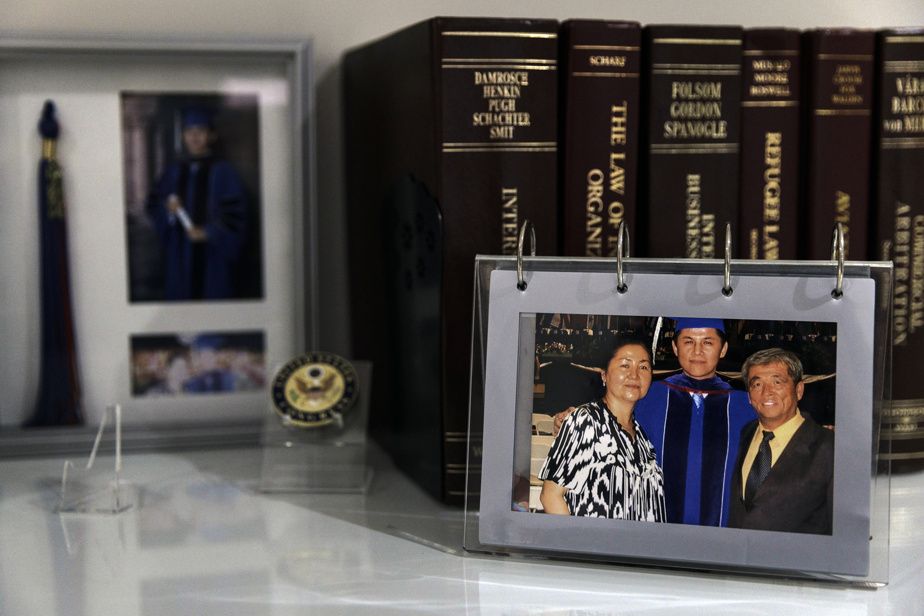

PHOTO MORIAH RATNER, THE NEW YORK TIMES

This 2004 photo, taken at the law graduation of Nury Turkel (center), with his mother Ayshem Mamut and father Ablikim Mömin, was prominently displayed at Mr. Turkel's home when he welcomed his mother into his home. him, 20 years later.

Relations between the United States and China reached their lowest point in early 2023, when a Chinese spy balloon was detected above the United States. Mr. Turkel was losing hope and expressed his frustration in publications and in appearances before Congress.

But American officials persisted. According to Mr. Turkel, President Biden mentioned his mother during a meeting with Mr. Xi in Woodside, California, in November 2023, and again last November in Lima, Peru.

PHOTO ERIC LEE, ARCHIVES THE NEW YORK TIMES

According to Mr. Turkel, President Biden mentioned his mother during a meeting with Mr. Xi in November in Lima, Peru.

Then, on November 24, a White House official told Mr. Turkel that his mother would shortly be leaving China on a U.S. government plane. It was around the same time that the police went to look for Mme Mamut at home. Mr. Turkel contacted her by telephone and told her to do whatever the police told her to do.

She visited her husband's grave, then packed a bag of traditional Uyghur silk fabrics that she could use to make clothes for her grandchildren in the United States. The next morning, she took a charter plane to Beijing with police officers and the two other Uyghurs, a man and his daughter.

That night, the three of them slept in a government house in Beijing. Their departure was delayed by six hours, which made them nervous. They were then taken to the airport, where the U.S. government-chartered plane was waiting for them.

Ambassador Burns accompanied them onto the plane and took photos with them inside. The three freed American prisoners – Mark Swidan, Kai Li and John Leung – were on the plane, as were Roger D. Carstens, the special presidential envoy for hostage affairs, and other officials. Americans. One of the diplomats put Mme Mamut in telephone contact with his son.

After takeoff, all the Uyghurs cried with emotion.

This article was originally published in the New York Times.

Read the original article from New York Times (in English, subscription required)