From the columns of “Positif” to the debates of “Masque et la plume”, this master of film criticism defended the existence of places of exchange, analysis and thought. One year after his death, on November 13, 2023, we are republishing our interview conducted in 1994.

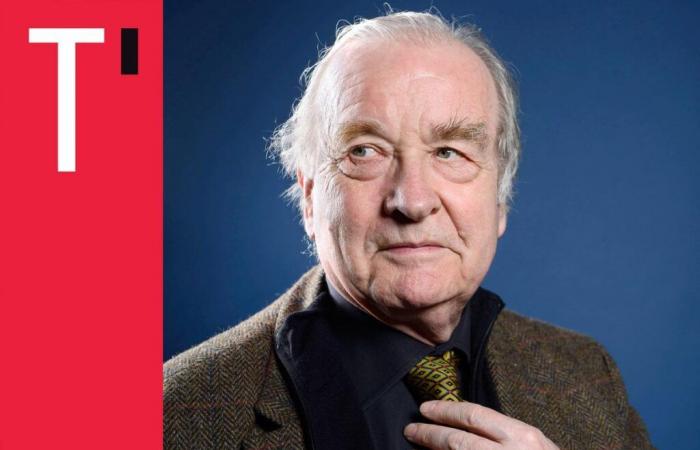

Michel Ciment in 2013, during the French Cinema Critics Union awards ceremony. Photo JP Baltel/Bureau233

By Vincent Remy

Published on November 13, 2024 at 10:00 a.m.

Pape of criticism, Michel Ciment? Rather, a soldier monk, fighting on all fronts of cinephilia: president of the Critics' Union, host of the review Positive, it is also critical to Globe and regular collaborator of Mask and feather. Lecturer at the University of Paris-VII, he teaches American civilization, and therefore cinema. We no longer count his works (Kazan by Kazan, Le Livre de Losey, Kubrick, Boorman, etc.). Disappearing critics? This is not Michel Ciment's opinion. In any case, if there was only one left, it would be this one…

How do you become a film critic?

Not by vocation in any case! I wanted to be a historian. The only thing we can say is that you have to love cinema. It started with me at a very young age, around 12, when I discovered Saturday night cinema.

Not yet a big movie buff, so…

No, but it came very quickly, in high school, at 16 years old.

And History?

For me, it corresponded to the beginning of political commitment. I was in hypokhâgne at Louis-le-Grand. By 1956, Budapest had stripped me of all illusions about communism. But it was the Algerian war, I was for Mendès France, I had sympathy for the reprobate. All things that I did not find in teaching. On the other hand, I had Deleuze as a philosophy teacher, with whom I discussed Jerry Lewis and Stroheim. I started going to the Cinémathèque, rue d’Ulm. It was the time of the great retrospectives organized by Langlois: Stroheim, Buster Keaton, Harry Langdon. With silent films, I really discovered the existence of a cinematographic language.

Podium

We have classified all of François Truffaut's films, from the most minor to the masterpiece

And you started writing. Why in Positive and not in the Cinema notebooks ?

I read both, I had a lot of esteem for Truffaut, Rohmer, Rivette, as I had for Benayoun or Tailleur. I loved Hawks, Dreyer and Rossellini as much as Buñuel, Huston and Antonioni, since these were the great divisions of the time. But, at Positive, we did not consider cinema as an isolated phenomenon. I found people there jumping from a Visconti film to a Matta painting or a Borges short story. And then it was a period of political engagement. For me, cinema was not only about strikes on the screen, but also about strikes in life. Critics of Positive, very marked by the surrealists, reconciled my political commitments and my artistic tastes.

And today?

I see a kind of resistance in my work! In the past, there was a certain agreement on what criticism should be. For fifteen years, between approximately 1953 and 1967, there was a golden age of criticism. Magazines proliferated. Cinephilia was a normal thing, just as it was normal – which seems unimaginable today – for all the critics to meet each year at the Tours festival to discover the latest animated films from McLaren or Trnka…

In any case, today, some of them declare that it is not necessary to know the history of cinema to be a critic.

Has this keen cinephilia disappeared among critics?

In any case, today, some of them declare that it is not necessary to know the history of cinema to be a critic. Truffaut said that we had to get used to the idea that one day films would be seen by people who were unaware of the existence of Dawn, from Murnau. Now, professional critics go beyond this statement: Truffaut was not thinking of critics when he said that! Can we imagine a literary critic who would consider it superfluous to have read Proust or Flaubert? When Godard observed: “We don’t say “an old novel”, but we say an old film”, unfortunately he was right.

Don't you think that we should fear a lack of curiosity more than a lack of culture?

The two are linked! We must maintain, even if it means appearing backward-looking, an all-out cinematic culture, retroactive – which questions the past – and geographical – that is to say going beyond the Franco-American framework. Critics are not the only ones to blame, some directors are too: Luc Besson boasted of not knowing where the Cinémathèque is. He should have known, though, since it's next to the old aquarium…

But some people think that culture can be cumbersome?

I don’t believe in “spontaneism”! All novelists began by reading, all painters began by looking, and all musicians began by listening. It is from the knowledge of what already exists that we can be revolutionary. The New Wave frequented silent films. And the passage through silent films is perhaps the key to the creation of cinema. His ignorance is the forgetting of the image, the forgetting of the frame.

In recent years, we no longer had the right to judge, to evaluate. However, life is a permanent choice!

So knowledge of cinema is for you the first quality of a critic?

This is a necessary quality. Not enough, obviously. You need, of course, analytical skills, and then evaluation criteria. There has been a lot of criticism of the value judgment. In recent years, we no longer had the right to judge, to evaluate. However, life is a permanent choice!

You write to Positive, but also to Globe, and you intervene Mask and feather. Does that seem coherent to you?

The important thing is to be true to yourself, to your vision of cinema. In The liberated Parisian, André Bazin did not write in the same way as in THE Notebooks. The important thing was that he recommended to the readers of Parisian a Rossellini, even if he did it in twenty-five lines, necessarily reductive. Conversely, I like Kubrick, a popular author, but I am not ashamed to defend him in Positive. The surrealists taught me to hate categories, the distinctions between noble art and popular art…

Do you think about your readers when you write?

Max Ophuls said that if you chase the audience so much, you end up only seeing your ass. It's the same thing for a critic. Newspaper directors who are starting to say to themselves: if we put that on the cover, it won't sell, it's catastrophic. When The City of Sorrows, by Hou Hsiao-hsien, whom I love and on which we wrote fifteen pages, made six thousand entries, it upsets me, but it doesn't change my choices!

Also read:

“The Mask and the Feather”: Jérôme Garcin’s last “Sunday evening”

Is that what resistance is?

Of course ! There are only a few newspapers left where you can make these choices. Formerly, in The Observer, Benayoun or Cournot could devote pages to Antonioni or to the resumption of The Red Empress, who went out to a room in Paris, because it was their pleasure. Today, newspaper editors say: no reviews, it bores everyone, write short, don't analyze films, do an interview with Sharon Stone instead. We refuse any explanation of judgment. Because, to judge, we judge: we give notes, we put stars, everything must be summarized in notes, in opinions bombarded in a few lines.

Maybe this is what the public is asking for?

So why do we see two-page literary reviews! Books are read much less than films are seen. If people are willing to read two pages of analysis on a Guatemalan novel they haven't read, why wouldn't they read a real review of a movie they've seen? The success of Mask and feather comes from a frustration: the public needs exchanges, arguments, not promotion. However, we are in an era of promoters.

The fault of the newspaper editors, then?

Not only that. When a journalist from Studio finds it astonishing that Resnais won Césars instead of Visitors, which attracted fourteen million spectators, we think we are dreaming. They are critics – in any case, they present themselves as such, since they express opinions every month – who go to meet the shopkeepers!

Does this tendency to only focus on numbers come from the United States?

But no, no major American newspaper gives the entry figures. In America, it is the responsibility of corporate newspapers, Variety, that is to say, a business newspaper. Why does it interest us that on average theaters, weighted by I don't know what coefficient, Christopher Frank's latest film had more or fewer admissions than Francis Girod's?

So American criticism is more resistant to pressure from Hollywood?

It depends: the provincial newspapers are entirely affiliated with the major companies. But, as a result, the major American newspapers make a point of doing real criticism: a critic of New Yorker has ten, twelve pages to talk about a film. THE New York Times, the Village Voice also provide considerable space for their critiques. And they don't care about the five biggest grossers in Los Angeles!

If we create critical spaces, we will see lots of young talents emerge.

Do you think the viewer is “sensitive” to the numbers?

Forty years ago, when a film didn't work in the United States, no one knew it. Truffaut, if, perhaps, knew that The Thirst for Evil hadn't worked, but it was all the more reason to defend him. Today, information travels so quickly that if Tartampion's film did not work in the United States, it is like a plague, we no longer even expect it in France.

Isn't there also a reverse trend?

It's true, in criticism, there is also the tendency: it doesn't work, therefore it is a masterpiece. Next to “the empire of fortune”, there is “the castle of purity”: any beginner would be a much greater filmmaker than Claude Sautet because he has six hundred spectators. We lock ourselves into frames, prejudices, and we forget to watch films…

Do you seem pessimistic about the future of criticism?

No, or rather, as Gramsci said, I have the pessimism of reason, the optimism of the will. If we create critical spaces, we will see lots of young talents emerge. In the past, the critic knew much more about cinema than the audience he was addressing. Today, a certain public, who has read a lot, and who has a lot of cassettes, sometimes knows more about cinema than the critic who talks to them about it. This new audience is a pool from which we will be able to draw criticism.

A breeding ground for criticism, but few places to express yourself.

So, it’s up to the big newspapers to start playing the game again!

Article published in the Telerama nᵒ 2313 of May 11, 1994.