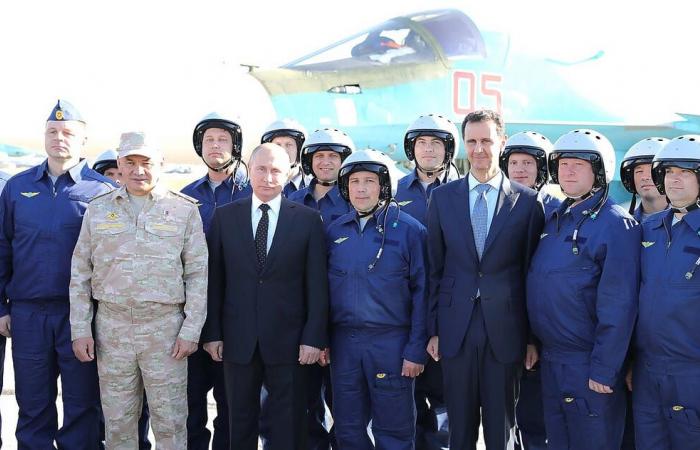

The Damascus regime fell and the Kremlin exfiltrated Bashar al-Assad, considered a sort of humanitarian refugee. Now the question of Russian bases in Syria arises. Notwithstanding the agitation observed there, their fate would be “unresolved” (Dmitri Peskov, December 16, 2024). Some speculate on the “pragmatism” of Vladimir Putin, ready to compromise with “armed fighters” and other “representatives of the opposition”. The strategic, and therefore geopolitical, issues are major. So it is important to push what falls.

The collapse of the Damascus regime on December 8 calls into question Russia's power and influence in Syria, which constitutes a historic turning point. The words are not overused: even though the French mandate, in the aftermath of the Second World War, was not completed, Moscow was delivering weapons and negotiating an alliance with Syria, an entry point into a region where England was still hegemonic; the history of diplomatic-strategic relations between Moscow and Damascus is long-term, with the famous “Eastern Question” and the so-called “warm seas” strategy as a backdrop. Also we should not believe that Putin, like a trader burned, will accept its losses to move on (the only Ukrainian front).

Already, Russian diplomacy affirms that Moscow is negotiating with “representatives of the opposition” (they are no longer “terrorists”) the preservation of its strategic “assets”, including the Tartous base (a war port) and the Hmeimim (an air base next to the civil airport); the Russian army also had around ten other bases now evacuated, under the protection of Turkish military forces. Beyond the Middle East, where many Sunni regimes had been impressed by Russian military engagement in Syria (in alliance with Iran), these bases made it possible to project its power in North Africa (Libya and beyond). beyond), in sub-Saharan Africa and the Horn of Africa.

Located halfway between the Turkish straits and the Suez Canal, the Tartous naval base is an essential logistics hub for deploying military assets with force and speed in Cyrenaica (eastern Libya), a relay to the Central African Republic and the Sahel countries, from which France was ousted. If Port Sudan, in the Red Sea, was another access route, favored until the Russians gained a foothold in Libya, the men (Wagner and their epigones), their equipment and the cargoes left the port of Tartous and from Hmeimim airport. Furthermore, the civil war in Sudan, where Russia is engaged on each of the two camps, has rendered the project of a large Russian naval base in the Red Sea (at Port Sudan) obsolete.

In short, these two bases constituted means of projecting power on the scale of the “Greater Mediterranean” and in Africa, with effects on other theaters. We must also take into account the Russian intelligence assets established on Syrian territory – they would have been withdrawn even before the fall of Damascus – a system which ensured surveillance of the Middle East and its surroundings. Thus the transfer of information and location data by the Russian army would have conditioned several attacks by the Houthis in the Red Sea against Western merchant ships, with the known impacts on traffic, inflation, in fine on the global economy.

Apart from the fact that the war of aggression in Ukraine absorbs the attention of the Kremlin and the Russian general staff, and that it consumes the required military and financial resources, it appears that Moscow, in the event of losing its bases in Syria, would have few other geostrategic options. In Cyrenaica, the port and airport infrastructures available to the Russian army would not compensate for this loss and, in this unstable theater, it would be perilous to finance their move upmarket. Does Russia even have the means? In Sudan, the ruthless civil war thwarts the Kremlin's naval and military ambitions; the Port-Sudan/Bangui/Bamako (and others) logistics axis is under attack.

In the Balkans, Serbia could make relay bases available to the Russian air force but we can think that the West has enough influence to dissuade Belgrade. Finally, the Russian Navy does not have a carrier group capable of projecting forces and power in the Mediterranean: its old aircraft carrier (“Admiral Kuznetsov”) is almost out of service and it cannot be compared to a mobile and sovereign (what a real aircraft carrier is). Theoretically, the Russian navy could build the helicopter carriers that France refused to deliver (the “Mistral” type projection and command ships), but this is compromised. Anyway, “ a helicopter carrier does not make a port, much less an airport » (Cyrille Gloaguen).

While Putin's views and resolve should not be underestimated, alternative strategic options are limited. Could the master of the Kremlin find common ground with a future Syrian government in order to preserve the Russian bases, counting on the intercession of his Turkish counterpart to do so? If Moscow and Ankara are indeed associated in a sort of conflictual synergy, it seems doubtful that Recep T. Erdoğan will not push the advantage in Syria. It is the law of the genre: the balance of power dictates the sharing of remains, in the Middle East as in the Caucasus or in Africa.

The new masters of Syria, if they assert themselves over the long term, would still have to be ready to pardon those who massively bombed them over the past decade. Especially since the Russian bases are located in the “Alawite redoubt”, the geographical base of the Assad clan; once the moment of political communication and confabulations has passed, the hour of settling scores between Sunnis and Alawites will ring, with what this implies in terms of threats to the security of the Russians in this geographical corner (if they are still there) . In short, it is likely that the supposedly reasoned Machiavellianism of the chancelleries will not absorb the power of the shock wave caused by the fall of the regime.

Moreover, Western powers should not rely on external factors or the “invisible hand” of universal history to resolve the case of the Russian presence in Syria. Certainly, the main theater is that of Ukraine where the Russian army threatens to break down the doors of Europe, seized within its historical and geocultural limits (from the Atlantic to the Don, the Tanais of the ancient Greeks). But this war is part of a broader space, from the Barents Sea to the Mediterranean, where NATO must stand together.

The Russian withdrawal from Syria will not be enough to make the decision and win in this global confrontation thought, designed and wanted by Putin, who considers himself at war against a “collective West” dedicated to slander. At least the evidence of Russian strategic failure in Syria, and the consumption of resources invested in the murderous Damascus regime, will modify the correlation of forces, with repercussions in other theaters and areas of power.

To achieve these strategic gains and push Russia back into this much-cherished Eurasia, Western powers must maintain their unity and push in the same direction. Certainly, their diplomacies are hard at work but we also hear calls for realism and accounting reason, as if a “great retrenchment” was going to disarm the logic of power and dissolve the very phenomenon of hostility. These would only be the poor masks of a paralysis of the will. On the contrary, they must ward off the specter of Hamlet and push what falls.

Associate professor of history and geography and researcher at the French Institute of Geopolitics (Paris VIII University). Author of several works, he works within the Thomas More Institute on geopolitical and defense issues in Europe. His research areas cover the Baltic-Black Sea area, post-Soviet Eurasia and the Mediterranean.