Snowfall at the Cinquantenaire park, in Brussels on January 17, 2024 ©BelgaImage

Since this Wednesday, snowball fights are back in Belgium. But could snowfall be rarer than before? Simple impression or real observation? To settle on the question, the Royal Meteorological Institute (IRM) delved into its archives. Conclusion: yes, global warming has had an impact on the occurrence of flakes on the flat country, even if there are some nuances to be made.

Snow is becoming rarer in Uccle

First, the IRM wanted to know if there are fewer snow days today than in the past. It appears that in Uccle, this number was on average 30-31 days per year. A figure that has never been reached since. “A first very marked decrease had already occurred around 1920”, notes the institute, then a second “in the 1990s, after warming beginning in the 1980s”. Currently, there is only an annual average of 19 days.

So yes, that does not prevent some recent years from being well supplied with snow. This was particularly the case in 2010, with even a record of more than 50 days on the clock. The occurrence of a Moscow-Paris type cold wave, like the one currently hitting Belgium, can help the snowflakes fall on our regions. But this is not necessarily good news, with part of the scientific community suggesting that global warming could favor this phenomenon, by destabilizing the polar wind regime.

The IRM also notes that in Uccle, the thickness of the highest layer of snow ever recorded dates from 1925. That time, no less than 34 cm had accumulated on the ground. But “since warming in the 1980s, values have been generally low, except in the early 2010s.” Since 1891, residents of the capital have only experienced two years without any trace of snow, and both are recent. These are 1989 and 2014.

The Ardennes also affected

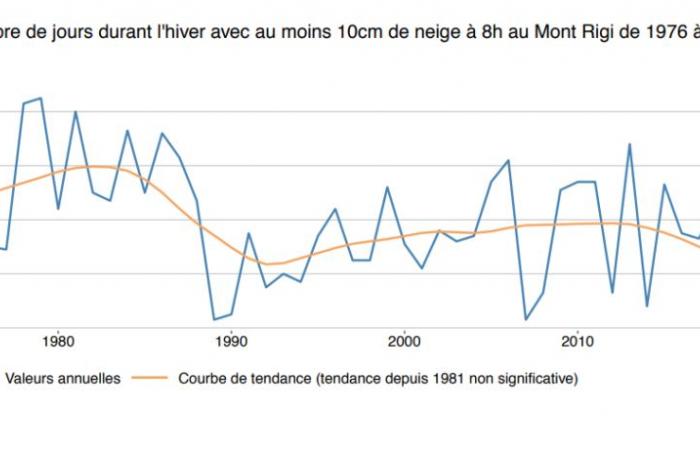

To confirm Uccle’s observations, the MRI looked at what was happening in the snowiest regions, namely in the Ardennes. At Mont-Rigi, even if the oldest archives only date from the 1970s and are less complete, the trend is clear there too. Around 1980, there were nearly 60 days of snow per year there with more than 10 cm on the ground. In the 2010s, the average dropped to 38 days and according to the latest readings, the 20 day mark has even been reached.

©IRM

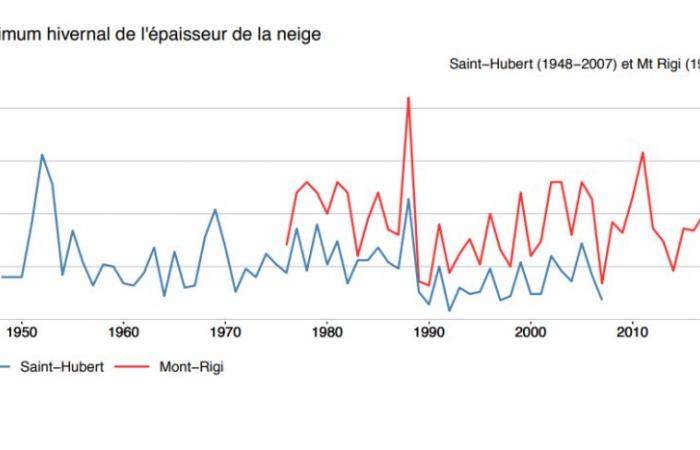

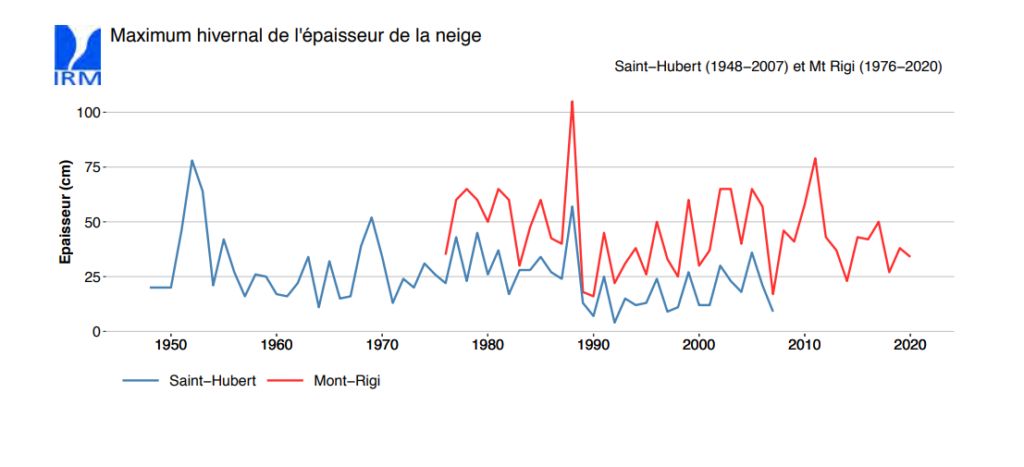

So it’s a fact: it’s snowing less than before. But what about the maximum snow depth in the Ardennes? Here, the evolution is less obvious. There was a “significant decrease, particularly in the 1990s”. But since then, the average has been raised by “a few winters with high maximum snowfall, particularly around 2010”. In other words, it snows less often but when it does, the quantities of flakes can be significant, with large variations depending on the year.

©IRM

Other countries also concerned

So far, we have only talked about Belgium. But elsewhere too, we notice a similar trend. Among our French neighbors, Ouest-France provides some evocative examples. In Rouen, there were 19 days of snow per year between 1961 and 1990. Between 1991 and 2020, this average fell to 11. In Orly, near Paris, this amount fell from 16 to 13 days. Same report in Bourges, in the center of France, which went from 15 to 13.

In Switzerland, if the snow holds up at high altitude, the authorities are especially concerned about mid-altitude Alpine resorts, where the figures are particularly worrying. In Einsiedeln, in the center of the country, the number of days with at least 1 cm on the ground fell from 140 in the early 1970s to 80 in the late 2010s.

More generally, the duration of persistence of snow cover on the ground has decreased by 5.6% per decade in the Alps, according to a study published in Nature. This layer of alpine snow even decreased by 36 days compared to “the long-term average”, note the authors. A particularly problematic observation since its rarefaction prevents the return of solar rays towards space, they add. In other words, rocks absorb solar energy more often, which contributes even more to global warming.

In Canada, the news is not more reassuring. 90% of the country’s weather stations have noticed a drop in the number of snowy days. In Montreal, the months of December, January and February are 1.8 degrees warmer in 2008-2017 than in 1874-1883, notes -. In the Quebec metropolis, the number of days above zero increased by 35% over the same period. Result: the maximum snow depth, which was around 60 cm in 1955-1975, melted by half in 1996-2015.

Greenhouse gases singled out

Faced with this global evolution, researchers have looked further into the subject and published a study in the journal Nature. By combining climate models and four decades of snow cover records, they confirmed what was feared. The decline in snowfall is indeed linked to greenhouse gas emissions. They are particularly concerned about snow located in regions below -8°C, where even “marginal increases in temperature imply increasingly significant snow losses”. In the northern hemisphere, 20% of snow is in this type of situation.

The authors point out that this could seriously disrupt the water cycle around the world. Among the areas most at risk are central and eastern Europe, as well as the southwest and northeast of the United States. There, snow cover has already decreased by 10 to 20% per decade since the 1980s. The Danube and Upper Mississippi basins have consequently seen a drop in their water level of 20-40%. Hence the need to react to global warming, the researchers conclude. But even if greenhouse gas emissions drop radically, we must still expect the trend to continue, even if the damage would be limited.