Industrialization of the economy is a national priority, in both developed and developing countries. Compared to other sectors of activity, notably agriculture and services, industry is generally perceived as being the only sector capable of generating mass employment, including for unskilled workers, of supporting GDP growth, and high value-added exports. In addition, it has a unique ability to absorb and diffuse technology and place the domestic production system on a more complex product space. For example, thanks to industry, China was able to double its GDP per capita in less than 10 years, not to mention the hundreds of millions of jobs created by its economy.

An industrial legacy that has crumbled over time

In Senegal, the first investment code dates from 1962, and was directly aimed at promoting manufacturing activity. A dedicated ministry (Ministry of Industrial Development and Crafts) has been set up, alongside an impressive institutional system (SONEPI, industrial free zones, etc.) aimed at industrial promotion. Well before independence, Senegal, which was home to the capital of the French colonial empire, also included most of the basic infrastructure of French West Africa, including the port, the airport and a good part of the road network. and railway. It also monopolized most of the raw materials processing industry, the exploitation of which formed the backbone of the slave trade economy.

At independence, two phenomena combined to trigger the decline of the national industrial base, which would prove irreversible over time:

a) The newly independent countries of France quickly set about developing their own manufacturing activity, and therefore erected trade barriers to protect their own industry.

b) Senegal has put in place an ineffective system for promoting so-called emerging industries, through a protection system, without any compensation from the beneficiaries, largely subsidized by the consumer.

In my opinion, this second reason was more decisive in the disappearance of Senegalese manufacturing activity, since otherwise nothing prevented the Senegalese industrial fabric from redeploying towards the world market, which is larger and offers almost unlimited outlets for most of its export products at the time. Before the devaluation, most sub-sectors of the Senegalese manufacturing sector had experienced a substantial decline in their value added and exports. Between 1984 and 1993, textiles recorded negative annual growth of more than 5%, compared to growth of -13.5% for oil manufacturing and -15.8% for clothing. Post-devaluation has made it possible to record a boom in the manufacturing sector, but which is largely driven by products characterized either by their low level of complexity (such as fishing), or by the existence of captive markets (such as chemical industry), but he never really recovered from his lethargy.

The early de-industrialization equation

The industrial sector (manufacturing activity) has always been the elevator that allows poor countries to engage in a dynamic of growth in per capita income, generation of quality jobs and, in turn, reduction of poverty. poverty. The countries of Western Europe, North America, and the emerging countries of Southeast Asia have all taken the same path to industrialization, boosting both GDP per capita and jobs. But it seems that since the emergence of China, the elevator no longer seems to work for poor countries. Contemporary economic history teaches us that as a country develops, the share of manufacturing in GDP and total employment increases, eventually peaks, and begins to decline. What is paradoxically observed today is that this peak of industrialization is reached by developing countries, for lower income levels. Furthermore, the peaks themselves correspond to lower levels of value added in relation to GDP and of manufactured jobs in relation to total employment.

The root causes of this decline in the share of the manufacturing sector in the GDP and in employment of developing countries are to be found in the significant changes that the industrial sector has undergone on an international scale. Now, there are global value chains that control the international production and marketing systems of goods and services. For most manufactured products, the production cycle has become fragmented with many countries participating in the production of the final product. The most striking example is that of the phone, where different parts of the product are produced in different countries and the software in the USA. Production and distribution ecosystems involve actors located in different countries, through simple subcontracting relationships. Each of the participating actors must obey quality and cost requirements, which many African countries cannot meet.

The necessary control of production costs

If Senegal, like other African countries, has never been able to integrate global value chains, it is because they have always experienced difficulties in complying with quality standards, but especially those linked to control of production costs. Senegal is the third country in the world with the most unfavorable labor legislation for businesses. Out of a sample of 189 countries, it ranks 187th, behind France. The cost of labor (salary compared to productivity) is among the highest in the world. Infrastructure services (water, electricity, roads, etc.) are also expensive and often of poor quality. Furthermore, the quality of the bureaucracy remains highly improvable, in particular the quality of services to private companies. Institutions remain fragile, with a high probability of a change in the rules of the game, particularly those governing business. These factors combined make it more profitable and much less risky for any investor to head towards countries with a friendlier business environment towards companies. This means that, outside of the informal sector, only activities relatively sheltered from global competition manage to survive in this particularly hostile ecosystem for private enterprise.

Wanting to correct all the price distortions affecting the factors of production in Senegal would be a challenge, as the investments and reforms involved are enormous, not to mention the social conflicts that could arise from any attempt to reform the status quo. Industrial parks could be ideal spaces for, on a reduced scale, setting up the right incentive system for a more dynamic ecosystem of private entrepreneurship. This presupposes that the operating methods of the parks must first be redesigned to make them more operational.*

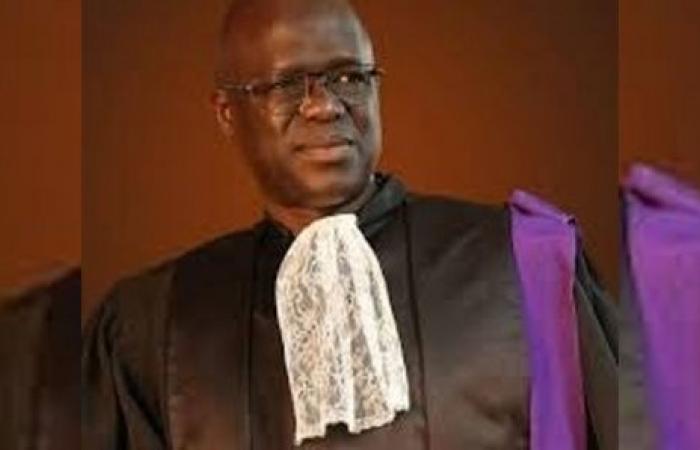

Ahmadou Aly Mbaye

Professor of Economics and Public Policy

Cheikh Anta Diop University of Dakar (UCAD)