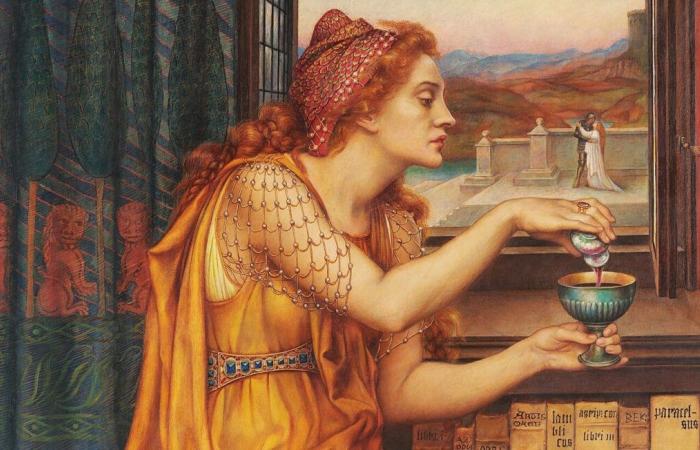

You may have come across them while scrolling on social networks, without understanding what they implied. More and more women are filming themselves, smiling, slipping a few drops of a mysterious liquid into glasses. This production depicts the poisoning of a drink by aqua tofana, a poison created in Italy, according to legend, by Giulia Tofana.

The MATGA (Make aqua tofana great again) movement, a nod to the famous MAGA (Make America Great Again) of Donald Trump, freshly re-elected as head of the United States, was born. Coming from the United States, it is a reappropriation of the story of Giulia Tofana who allegedly sold her poison to hundreds of women. And thanks to whom more than 600 of them have managed to escape a marriage with a violent man.

A poisoner and a group of women hanged

“In the 16th and 17th centuries, a trade in poisoned water developed in Italy and throughout Europe and reactivated the fear of poisoning. There are several versions of the origins of aqua tofana. The legend begins with Teofania di Adamo, who was executed in Palermo for poisoning in 1633. Then, in 1659 in Rome, a group of women were hanged for trading in poisoned water called aqua tofana,” relates Margaux Buyck, associate researcher at Paris Nanterre University and member of the Memo laboratory.

As for Giulia Tofana, “her existence is more uncertain, some sources present her as the daughter or granddaughter of Teofania di Adamo who would have migrated to Rome to continue her ancestor's business,” explains historian Margaux Buyck.

A “silent butchery of husbands”

While it is difficult to know exactly whether the cases are linked or how many men died after ingesting aqua tofana, the poison undoubtedly left its mark on its era. In his biography of Pope Alexander VII, Cardinal Pietro Sforza Pallavicino also speaks of a “silent butchery of husbands”. Proof of the popularity and paranoia that surrounded this poison, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart confided on his deathbed his fear of having ingested it without his knowledge.

On Google Trends, the search for “Aqua toafana ingredients” jumped by 160% in the United States, and that for arsenic by 130%. At the same time, the keyword “antidote” displays +140% searches. “With this movement, we are reactivating an age-old male threat and fear, that of being poisoned by the hand of a woman,” analyzes Margaux Buyck.

While men threaten “your body, my choice”, a reference to abortion but also to rape, these women respond with the threat of poison. “Women have exploited this fear throughout history. We find traces of it since Antiquity,” explains the historian of poisons who cites numerous legal cases where domestic violence and poisoning were intertwined.

A reversal of stigma

On Instagram, tattoo artist Solène, aka “Solène the wasp”, published her interpretation of Giulia Tofana. “I discovered this painting recently and its story touched me, particularly in the context of the fight against violence against women, such as the Mazan trial,” explains the tattoo artist, who works in Paris. “It’s the symbol of a general anger among women,” she slips, specifying that her interpretation was immediately reserved and must be inked on Saturday.

By clicking on“I accept”you accept the deposit of cookies by external services and will thus have access to the content of our partners.

More information on the Cookie management policy page

I accept

“It’s interesting to see the figure of the poisoner, originally extremely negative, become a positive figure,” analyzes Margaux Buyck. Considering poisoners as women who emancipate themselves from men is an extremely recent, post-Me too, analysis. » The historian of poison cites Lady Gaga's music video, Paparazzi, as an example of this reversal of stigma. A precursor, the singer plays the role of a woman violated by her companion, and who ends up murdering him with poison.

“The New Witch”

“We are arriving at an era where the poisoner can become the new witch,” believes Margaux Buyck. The witch, a female figure hated for centuries, has today become a symbol of feminism. This recovery, however, is done by slightly twisting the story.

Because if aqua tofana (and, more generally, poison) was often used by women to get rid of their husbands, the victims were not systematically violent men. “We are witnessing a rewriting of history. The 1659 affair was in reality an association of criminals whose main goal was profit,” smiles Margaux Buyck. Rest assured, however, gentlemen. According to the historian of poison, the women who take up the legend of the aqua tofana “are in the register of symbolic threat, it is unlikely that there will be any acts of violence”.