In 2022, 173,000 people were counted at the mass on the third Sunday in October. There were 286,000 in 2016. In 2022, the Church could still rely on a nice group of 114,000 volunteers, compared to 163,000 six years earlier. If we look at the same years, the overall number of priests fell from 4,979 to 3,582, the number of parishes from 3,846 to 3,613, and the number of Catholic funerals from 48,407 (in 2017) to 41,900 five years later. Finally, only the percentage of Belgians considering themselves Catholic remained stable: 50%.

These statistics are eloquent, but insufficient to understand Catholicism. Faith is a spiritual and interior reality, often unspeakable, which plays out under the radar, in the hearts of the faithful. It is therefore not easily measured, any more than the cultural sediments patiently deposited by Christianity on the country’s soil.

“I can no longer live my mission as a priest with joy. It crushes me, kills me slowly. I am really afraid of collapsing.”

The influence of the social doctrine of the Church

These cultural remnants of Christianity are what Cécile Vanderpelen-Diagre brings together under the term “Christianity”. These are, for example, educational or healthcare institutions, unions and the associative world stemming from the Christian pillar, underlines this professor of contemporary history at the ULB, and author of the book Voices in the Century. Culture and Catholic Commitment in French-Speaking Belgium Since 1945 (published by Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles). These institutions no longer defend the exhaustiveness of Catholic doctrine, but they inherit its culture, she insists.

Above all, they implicitly perpetuate a personalist conception of society. This movement, led in particular by the French Catholic Emmanuel Mounier (1905-1950), thought of itself as a third way between capitalism and Marxism. It intended to take care of the community in which each person evolved so that they could develop their own talents.

These institutions have also been strongly influenced by the social doctrine of the Church, which advocates subsidiarity (respect for the autonomy of local authorities). This form of decentralization, which is found for example in Catholic schools, explains the investment of teachers, parents, and volunteers within them, but also the fact that some establishments have remained closer to the Church than others.

The influence that social Christianity and personalism had on the country is still evident, argues the historian, and partly characterises Belgian sociology and the liveliness of its associative and cultural fabric.

And it is probably not over yet. The Belgian associative world, involved in social and climate justice, feels supported by Pope Francis, notes Jean-François Lauwens, head of the political service of Entraide et Fraternité. “And I hear many Christians who are far from the institution who are touched by the Pope, without this reaffiliating them to the Church.”adds Cécile Vanderpelen.

Two continents moving apart

Professor of canon law, writer, and honorary rector of the KULeuven, Rik Torfs qualifies this observation. The speeches given by the organizations belonging to the Christian pillar now have very little to do with their ancient tradition, and are far removed from Catholic doctrine. The wish of Luc Van Gorp, president of the National Alliance of Dutch-speaking Christian Mutualities, to broaden access to euthanasia is proof of this, in his eyes. The recent introduction into Catholic schools of the content of the Evras Guide (relating to relational, emotional and sexual life) is another: this guide from the Wallonia-Brussels Federation is based on a conception of human nature that is far removed from what the Church says about it.

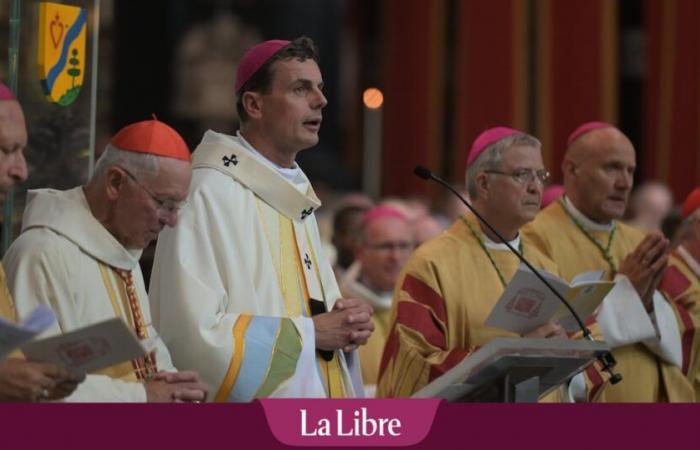

When ethical and cultural debates animate society, the latter, moreover, prudently recalls its position, but no longer mounts the barricades. It seeks to share its virtues and its doctrine through its social works, more than through explicit positions. The Church must ““to testify” of what the Gospel invites you to, but nothing “impose” and not “to impose oneself”summarized Cardinal Jozeph De Kesel, former Archbishop of Malines-Brussels, in 2021. This line, defined in his book Faith and Religion in a Modern Society (Éditions Salvator) is the one that is followed, for the moment, by his successor Luc Terlinden.

The bishops argue the validity of this position by relying on the gospels, but their attitude can also be explained by the social climate, mainly in Flanders. After the crimes of paedophilia and the omnipotent place that the Church held there in the 20th century, the north of the country is experiencing a kind of “postponed pain”emphasizes Rik Torfs. “The Church is weak there today, its credibility is deeply damaged, but it is made to understand how inadequate its place was in the past”. “This is followed by a fear, among the institution’s leaders, of committing new mistakes and being criticized. This induces a certain conformism, a great deal of caution. The institution evokes social values, but places little emphasis on the centrality of faith in God. The program of the Pope’s visit, centered around ecology and migration, is an illustration of this.”

This position is not without causing internal unrest. In a post-Catholic world, the faithful consider that bishops must be more assertive if they still want to make the “Good News” resonate.

In Brussels, the great puzzle of the reassignment of churches

A new model to invent

Structurally, the Church is also navigating between two waters. For centuries, its territorial presence has been based on the network of parishes and access to the sacraments given by priests (mass, confession, marriage, etc.). This network, which still arouses real attachment on the part of Catholics, cannot be swept aside with a wave of the hand, but it has become cumbersome, discouraging and impossible to maintain due to a lack of priestly vocations and goodwill to take over the management of the Church factories (which ensure the material management of the bell towers). The institution must therefore invent a new model, without selling off the heritage of the past or access to the sacraments that are essential to it. The challenge is therefore considerable. For many, the Church, tomorrow, will be made up of “warm homes”: living but rarer parishes towards which the faithful will converge. The image is beautiful, but it carries a risk: that parishes become “elective”, chosen by the faithful who share the same sensibilities, and therefore less open and “universal”.

Many paradoxes

This challenge of unity is all the greater since “Papa’s Church” no longer exists. Every week, under the dome of the Koekelberg Basilica, the faithful of 34 nationalities gather, while mass is celebrated in more than twenty languages in the capital, foreign diasporas support several bell towers and African priests carry the Walloon parishes on their shoulders. When going through the list of registrations for the Pope’s mass in Brussels, the organizing committee was happily surprised by the diversity of names, as well as the multiplicity of small donations of 10, 20 or 50 euros (“thousands”) sent by the faithful to finance the papal visit. So many signs, in their eyes, of the social diversity of the Catholic people. This diversity is also felt in the multiplicity of small ecological, social and spiritual initiatives (group housing, cafés, market gardens, etc.) that are springing up at the foot of the institution. This breeding ground, astonishing in its diversity, is the subject of studies by UCLouvain (via its Ecclesialab laboratory) and could foreshadow what the Church will be like tomorrow: less a heavy institution than a set of places combining prayer, intellectual, social and manual work.

“I think the Pope’s speech has percolated”: behind the institutional burdens, the Church sees the birth of small “start-ups”

All this is not without paradoxes. The younger generation seems more classical in its approach to prayer. We are witnessing, for example, the return of confession, as well as that of rites snubbed in the 20th century: kneeling. A simple and popular faith around the devotion of saints and the veneration of relics is also making a comeback, pushed by the diasporas and Pope Francis who likes to restore its reputation. Not to mention the growth in the number of adults requesting baptism in the West (362 in Belgium this year). This is “a phenomenon to observe”notes Cécile Vaderpelen. Until now, the Christian faith was transmitted sociologically from parents to children: “in a society of consent” where everyone chooses their affiliations, this will no longer be the case. The Church will have to adapt to this new reality.

Finally, how will it respond to the major intellectual questions of the time (transhumanism, artificial intelligence, gender, anti-speciesism, etc.) and – above all – to the thirst for meaning and spirituality that many sociologists are pointing out? This thirst was quenched until now by the great monotheisms. This is no longer the case. The West now draws on Eastern spiritualities, shamanism, esotericism, Islam or Protestant Pentecostalism, and heals itself through psychology and personal development. So many trends that show that the quest for transcendence and meaning is no less great than in the past, but that the Church is no longer just one offer among others.

Will it make its mark there? And with what face? A more colorful face, like society, or a more classic one because it is gathered around a core of convinced people? How will it assume its minority status?The future depends on us, on the enthusiasm and joy we put into it.insists Véronique Bontemps, a volunteer in Brussels. And we are never safe from a surprise. Every day, I am struck by the generosity and beauty of what is experienced on the ground, in volunteer work, far from the cameras.”

The history of the Church in Belgium is therefore not over, but its future is a formidable unknown. It will be interesting to see the ways in which the Pope will encourage it.

On YouTube, Instagram and TikTok, classical Catholicism is making a comeback