Since Antiquity, philosophers and historians have sought the origins of painting, as obscure as those of language, remedying the silence of history through mythical narrative. Closer to us, at the dawn of the Renaissance, efforts were made to find an origin for the renewal, for the resurrection of painting which manifested itself at the end of the 13th century in Tuscany, and this absolute beginning bears the name of Cimabue, born Cenni di Pepi around 1250 in Florence. The Louvre museum is dedicating an exceptional exhibition to him on the occasion of the restoration of his splendid Majesty and the acquisition (in 2023) of The Derision of Christa previously unpublished panel by Cimabue rediscovered in France in private homes in 2019 and classified as a National Treasure.

A master celebrated since the Renaissance, from Dante to Vasari

Quoted in the Purgatory of Dante, one of his contemporaries, Cimabue was brought to the pinnacle in 1400 by Filippo Villani, historian of the city of Florence and its illustrious men: Cimabue “ the first, recalled the Art of painting in the likeness of nature “. In 1481, the scholar Cristoforo Landino did not say anything else in his preface to The Divine Comedy : « The first was therefore Giovanni, a Florentine named Cimabue, who found both the natural lines of physiognomies and the true proportion that the Greeks call symmetry ; and he brought back life and ease of gesture to the characters who would have been said to be dead by the ancient painters; he left behind him a great reputation. » This reputation will be amplified by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the best paintersItalian sculptors and architects (1568). The Tuscan historiographer is also the first to cite this Majesty from Cimabue.

A masterpiece from Pisa to the banks of the Seine

Painted around 1280, this monumental painting (4.24 meters by 2.76) was then in the church of San Francesco in Pisa, the most powerful city in central Italy in the 13th century. In 1812, the Majesty was taken by the French troops to Paris, where it was exhibited at the Louvre from 1814. In the same lot appeared the no less famous Saint Francis receiving the stigmata of Giottoalso preserved on the banks of the Seine. Of the sixteen paintings mentioned by Vasari, only four of the remaining eleven are still attributed to Cimabue and, among these, some, such as the Crucifix of Santa Croce, in Florence, or the frescoes of the Basilica of Assisi, suffered irreparable damage. This shows the importance of the Louvre altarpiece for understanding the break accomplished by Cimabue with the Byzantine tradition, dominant in Italy throughout the Duecento.

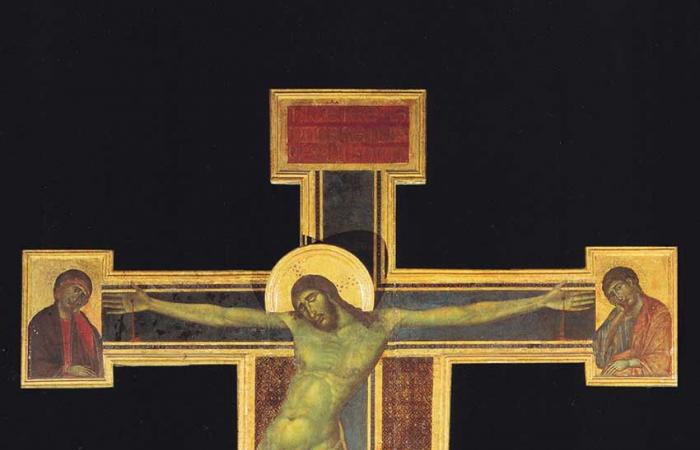

Cimabue, Crucifix (before the floods of 1966), Santa Croce church, circa 1272-1288, tempera and gold on wood, 448 x 390 cm, Museum of the Work of Santa Croce in Florence © Wikimedia Commons

The throne of wisdom: symbolism and plastic function

The power of the painting comes first of all from the simplicity, the symmetrical rigor of its composition: the Virgin and Child on her throne, represented in majesty (hence the name of Majesty), is surrounded by six angels, three on each side, while the frame is decorated with twenty-six medallions housing bust figures. In an order consistent with the celestial hierarchy, they represent, from top to bottom, God surrounded by angels, the Evangelists, the apostles and, at the base, five saints including Saint Francis of Assisi. But the monumental throne on which the Madonna sits is certainly the most intriguing element of the panel.

Cenni di Pepo, known as Cimabue (Florence, around 1240 – Pisa, 1302), The Virgin and Child in Majesty surrounded by six angels (Maestà), 1280-1290, tempera on gold ground on wood (poplar). Louvre Museum © C2RMF / Thomas Clot

In richly carved wood, once inlaid with gold, this traditional attribute of Mary is a good key to entering the work. It alludes in fact to Marian theology which, in the wake of the councils of Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (45i), considered the Virgin as the throne on which divine wisdom sat, in this case Christ. This is why she was often referred to as “ the seat of wisdom » (seat of Wisdom). Through this metonymic doubling, the majesty of the “mother of God” is underlined. This throne, the back of which is covered with an Arabic fabric decorated with Kufic and Naskhi characters, also plays an essential role in the figurative device and sheds light on Villani’s considerations on resemblance with nature. Represented in perspective, it literally frees itself from the surface and its volume not only gives density to the scene, but also creates a link with the world below, denied by the gold background, a symbol of the divine.

-Going beyond the Byzantine tradition to bring together the human and the divine

Search for truth and stylization thus enter into tension in the field of the painting. But the irruption of nature is not limited to this symbolic accessory. On the faces, the rigor of the line is softened by the subtle modulation of chiaroscuro, which not only gives volume and materiality to the bodies, but also contributes to the search for expression. Because, beyond the discourse on Cimabue’s place in the history of art, his relationships with Byzantine painting on the one hand, with Giotto on the other, the contemporary spectator is first of all sensitive to the gentle melancholy which permeates the figures of the Virgin and the angels, inhabited by the presentiment of the Passion. In contrast with the dazzling gold background, the delicate chromaticism, just enhanced by the shimmering wings of the angels, adds to the atmosphere of meditation and contemplation.

Byzantine painter, Madonna Kahn, circa 1272-1282, tempera and gold on wood, poplar (panel), fir (frame) H. 130; L. 77 cm. Washington, National Gallery of Art, inv. 1949-7.1, donation by Otto H. Kahn. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Certainly, the Majesty still bears the marks of Byzantine painting, through the graphic play of folds which shines in the blue mantle of the Virgin or the very stylized drawing of the anatomical details. But, in such a picture, a radical mutation takes place which, for the authority of the Ancients, substitutes the value of novelty. Cimabue « triumphed over Greek cultural habits, which seemed to pass from one to the other: we imitated without ever adding anything to the practice of the masters. He consulted nature, animated the faces, folded the fabrics, placed the characters with much more art than the Greeks had done. » This analysis, formulated by the historian Luigi Lanzi at the end of the 18th century in his Pictorial history of Italy (1795-1796), retains all its relevance.

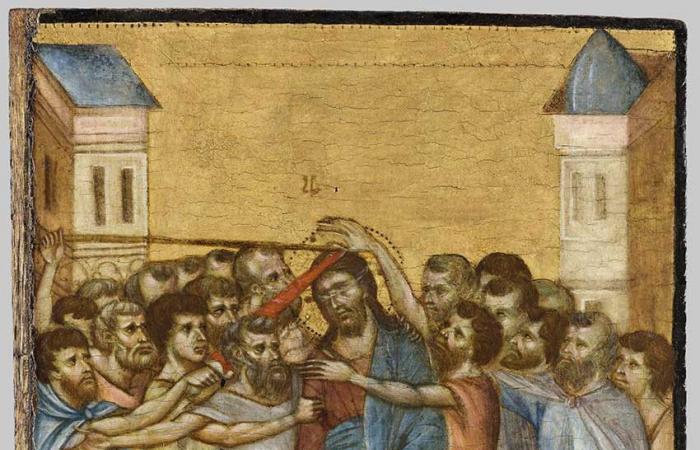

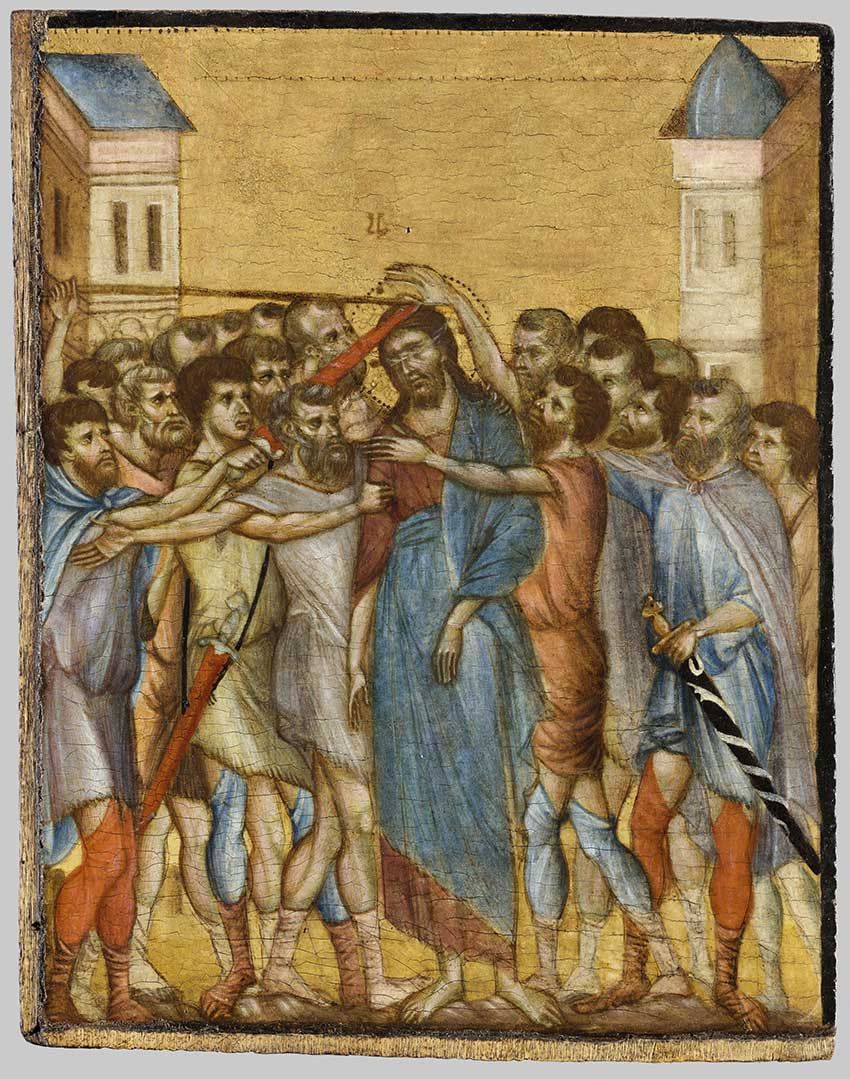

Cimabue, The Derision of Christ, circa 1285-1290, painted on wood (poplar) H. 25.8; L. 8 inches. Louvre Museum © GrandPalaisRmn (Louvre Museum) / Gabriel de Carvalho

that the Majesty was painted, in all likelihood, for a church dedicated to Saint Francis of Assisi, is not indifferent, if we want to go beyond formal considerations and shed light on the close relationships that the evolution of the style maintains with spirituality Franciscan. This reaffirms the presence of Christ in the world and invites us to look at Creation as the manifestation of this presence. It thus reaffirms the contiguity of the divine and the human. Giotto, Cimabue’s student, will give the most accomplished pictorial interpretation of this sensitivity.

“See Cimabue again. At the origins of Italian painting »

Louvre Museum, Paris

From January 22 to May 12, 2025

Presentation of the exhibition See Cimabue again. At the origins of Italian painting”