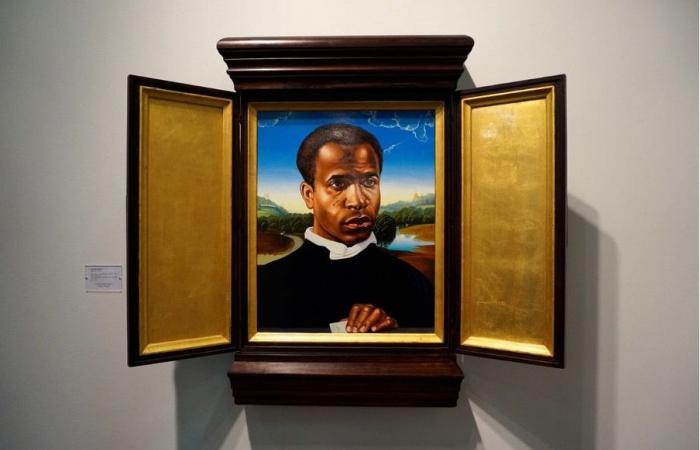

In 2013, African-American painter Kehinde Wiley created a portrait of Frantz Fanon. The face of the Martinique psychiatrist and revolutionary appears there against a background of bright blue sky, taking up the codes of a Flemish painting from XVe century. Wiley surrounds it with two gilded wooden panels, forming a sort of icon before which people would come to meditate. The artist seems to offer us a sort of canonization of Fanon.

Like many revolutionaries who died young, from Che Guevara to Thomas Sankara, Frantz Fanon is an icon. Compared to his peers, Fanon is known less for his image than for his writings. We have seen such an appetite for his work for several years that he has probably never been read so much. To understand the psychological effects of racism, to reflect on the violent and profound inequality that runs through our world, Fanon’s writings remain so burning today that they are often read like prophecies. Whether it’s police violence against black people in the United States or France, or the terror that befalls Palestinians in Gaza, a quote from Fanon is never far away.

The new biography of Fanon by Adam Shatz, an American literary journalist, is part of this renewed interest. Published simultaneously in its original English and in a French version translated by Marc Saint-Upéry (which is discussed here), it is part of important editorial news on Frantz Fanon. Shatz himself, as he writes at the end of the book, became fascinated with this life while reading a previous biography of the man, published by David Macey in 2000. [1] But Shatz also writes to criticize certain aspects of this trend, notably what he perceives as a “ idôlatrisation » by Fanon: “ my admiration for him is not unconditional, and I believe that his memory is not well served by sanctification enterprises » (p. 17).

Crossed portraits

What does this attempt to remove the portrait of a man from his golden altarpiece reveal to us? ? The life of Frantz Fanon is fascinating in itself, and his story is served here by generous research and precise writing. Shatz takes us from his childhood in a bourgeois family in Martinique to his years of medical studies in France, before detailing his practice of psychiatry in Algeria, which quickly doubled as a career as an activist for FLNfirst in Algeria then in Tunis and in several other African countries. At each stage, the author offers a fine contextualization of the different worlds that Fanon crosses, offering useful summaries of subjects as diverse as the development of institutional psychiatry or the decolonization of the Belgian Congo.

Most often, Shatz offers them to us through the individual scale, through crossed portraits. We thus come across a gallery of characters around Fanon, from a West Indian intellectual like Aimé Césaire, to existentialists like Jean-Paul Sartre, to psychiatrists like Octave Mannoni and François Tosquelles, and even other supporters of the FLN like Adolfo Kaminsky. What interests Shatz is above all to bring together people and debates of ideas, to revive a world in full turmoil in the 1950s. The book therefore forms a good introduction, for those who do not know it, to this world after the Second World War, when some people attempted to achieve a new understanding of the human being.

The indissoluble whole of Fanon’s life

If some of these characters are well known, even the connoisseur discovers certain surprising moments. Thus, Fanon’s expedition to Mali on behalf of the FLN in 1960, in order to obtain the opening of a new southern front in the Algerian war of independence, is one of the highlights of the work. If the episode was not very successful, we follow Fanon in the field, getting stuck in the interior Niger delta towards Gao, far from his office and his doctor’s coat.

One of the author’s choices is also to emphasize the multiple aspects of Fanon’s work: his clinical practice of psychiatry, his activities as a political leader, as well as the literary aspects of his writing. Fanon’s secretary, Marie-Jeanne Manuellan, whom Shatz met, is one of the central characters in the book. She also insists on this “ indissoluble whole “. The subject thus gives substance to the abundant complexity of the character, too often reduced to a theoretician.

From this point of view, Shatz relies on existing work, and in particular on work which marked a real turning point in studies on Fanon: the publication by Jean Khalfa and Robert Young of hitherto unpublished texts by Fanon under the title ofWritings on alienation and freedom in 2015 [2]. While Fanon is too often, as Shatz notes, reduced to his latest work, The Wretched of the Earth (1961), and especially in the first chapter of this one on violence, the publication of these scattered writings, ranging from plays to articles for the newspaper of FLN El Moudjahid allowed us to discover a more personal and more complex Fanon, and above all a great practitioner and theoretician of psychiatry.

Fanon against his American readings

Adam Shatz is not an academic, and therefore offers a lively and accessible synthesis. Perfectly documented, this work reads less as a work of primary research than as an intervention with political significance in the current intellectual landscape – why, otherwise, offer us a new book on Fanon, after that of Macey and so many others, including his portrait by one of his former collaborators, Alice Cherki [3] ? Shatz targets certain readings of Fanon that he considers erroneous, particularly in the United States. He evokes during the work those who make Fanon a “ champion of black identity » (p. 81-82), these “ contemporary Fanonians, who prefer his analysis of anti-black oppression and his pan-Africanism » (p. 117). In the epilogue in particular, we understand that the author attacks the “ type of racial essentialism that, in recent years, has become a commonplace of American progressivism. »

These adversaries, however, are not named by Shatz and their arguments must be understood implicitly. At least he briefly mentions, in the epilogue, the Afropessimism of Frank Wilderson (p. 420), a current of thought which perceives the black condition in a profoundly ontological manner and therefore does not believe in a possible transformation of this condition. racial. Such an interpretation thus leads to a reading of Fanon which evacuates the entire Algerian and revolutionary portion of his life to make him nothing more than a pessimistic theoretician. Adam Shatz’s remarks, however, tend to accumulate personalities and narrative details, favoring an implicit argument which sometimes leaves one uncertain as to the exact identity of those targeted by the author.

It is certain that the American intellectual debate tends to reduce racial issues in the world to the prism of the particular history of a country. In the United States, Fanon can thus be read in the light of a single prism: the one who diagnosed the Black problem in order to propose a remedy. In this way, Shatz seems to tell us, Fanon’s complexity would be largely eliminated. His deep links with metropolitan French existentialism first, but above all his commitment to a country foreign to him, Algeria. A country where the majority of residents did not perceive themselves as Black, a difference that did not prevent crucial solidarity from forming during the Algerian revolution. In an English-speaking context, the intellectual prestige of Fanon and the Battle of Algiers by Gillo Pontecorvo are inversely proportional to knowledge of the Maghreb. Very often, in English, Algeria, if we talk about it at all, appears as a sort of metaphor rather than a real territory populated by inhabitants. In this, it shares the destiny of another paradigmatic revolution against French colonization, Haiti.

Towards a global analysis of racial formations

But Fanon’s American readings, and their difficulty in understanding different racial formations around the world, prove symptomatic of a much larger and more structural question that runs through Fanon’s life: how to articulate racial situations in different contexts for make a joint analysis ? It’s sort of his life’s project.

Fanon begins with a first shift from the racial unthinking of Martinican society to his brutal realization of his own black condition in the metropolis. There his first theorization was born, that of Black skin, white masks (1952). Then, in the discovery of other societies in North and then West Africa, these new movements introduce new reflections, those of Wretched of the earth. During this journey, Fanon encounters multiple forms of racism. For example, as Shatz notes, in a post-war French society where the issue of anti-Semitism was dominant, Fanon encountered a number of Jewish intellectuals who were victims of racism without being colonized. Above all, Fanon encounters the anti-black racism of the North Africans, first during the Second World War, then regularly in Algeria and Tunisia. The question of the relationship between anti-black racism and other forms of racism does not only arise in the United States, and Fanon was not unaware of it.

Unfortunately, this question of internal racism in the Maghreb is only the subject of a footnote in Shatz’s book (p. 230). However, it is one example among others of the many questions that Fanon raises outside the context of the United States. It resurfaces today, for example, in debates on the place of anti-black racism in North African societies, where Fanon spent a good part of his most productive years, which resurface in the context of current events violent [4].

Adam Shatz invites us not to read Fanon like a bible. Through this salutary injunction can emerge a better understanding of all his literary wealth and the changing context which surrounds his writings, rather than seeing them as prophecies. However, removing Fanon from his altar perhaps not only involves finding the man behind the icon, but also makes it necessary to think about our racial present, and to find new political frameworks on a global scale capable of generating actions contributing to our collective emancipation. From this point of view, to go beyond the narrow readings of Fanon designated by Shatz, the biographical approach which participates in the wars of appropriation around a single man can only be a beginning, and not a key to current interpretation. racial formations.

Adam Shatz, Frantz Fanon. A life of revolutionsParis, La Découverte, 2024, 512 p., €28.