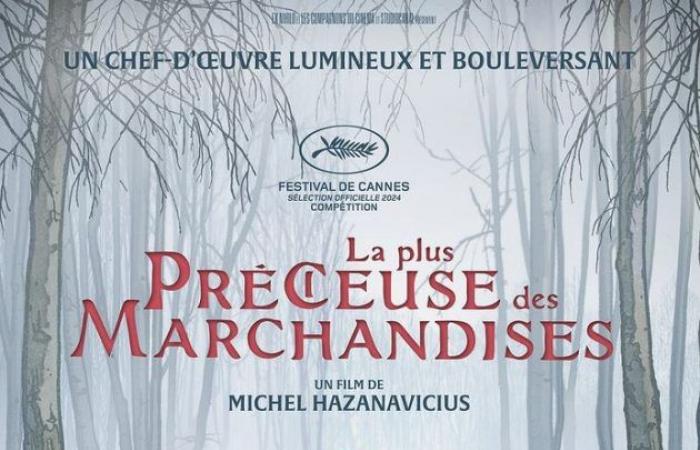

Night, fog and forest

With the black lines that mark the outline of faces, bodies and objects, the visual style of The Most Valuable of Goods affirms the importance of the line. In the Polish forest where the film takes place, the purity of the trees and clearings covered in snow is parasitized by railway lines, and by the trains which transport many innocent people there to their death.

This way of streaking the image, of marking it with the scars of Historyseems logical for a story haunted by the question of the representation of the extermination camps. Cinema has failed to document the horror of the Holocaust in its present. How could he do so in hindsight? This question, still burning, questions the ethics of such filming. The precepts of Claude Lanzmann (absence of the artifices of staging and archive images, direct testimonies, etc.) are confronted more than ever with the necessity of fictional reconstruction, at a time when the last survivors of the Holocaust disappear.

If he never takes on a device as powerful as that of The Area of InterestMichel Hazanavicius nevertheless finds an ideal crossroads with the book by Jean-Claude Grumberg. The animation de facto creates a distance from the real shot, and the director takes advantage of this to develop a falsely rough style, ultimately focused on the intoxicating beauty of a saving nature, this base of the “righteous” that presents the film faces war and its cruelty.

These “righteous” are this couple of lumberjacks who take in a baby thrown from a train, being more or less unconscious of the genocide taking place not far from their home. From this premise, Jean-Claude Grumberg drew a tale about the survival of human kindness, about light in the heart of darkness. To begin with, Michel Hazanavicius deploys his sense of periphrasis with finesse. The Jews are called the “heartless”, the Nazis are not named, and the heavy off-screen nature of the camps is felt.

Abjection?

It is surprisingly in these moments that the presence of the director ofOSS 117 takes on its full meaning. For the one who made himself known with the quality of his pastiches and for The Great Diversion, The Most Valuable of Goods also carries out a diversion: that of the taleits codes and metaphors which reimagine for children the horror of reality. While one might think the film complacent with its suggestive elements, the “Once upon a time” introductory refers to a History that is too hard for us to believe it to be true, too hard for us to face it.

The sublime voice-over of Jean-Louis Trintignant (in his last role) exudes a magnificent gravity, but also a fragility through his quavering tone, as if this testimony of the narrator was doomed to disappear, or even to be swallowed up by negationism. While this falsely Disney-esque forest ends up being overtaken by the reality of the Shoah, Hazanavicius is also aware that his film is necessarily overtaken by the present. From there, the filmmaker chooses to no longer play hide and seek and makes a clear transition, while a sequence follows a bird to Auschwitz.

It is once again a question of a line, of this limit of the representable materialized by a barbed wire. Against all odds, the director crosses it, tests a limit. The animation, until now made up of symbols and synecdoques, shows in full frame the emaciated bodies of the prisoners. We feel the film on a tightrope, without falling into the obscenity often criticized in other similar attempts.

No doubt this is due to the fact that The Most Valuable of Goods questions through its narrative and technical approach a necessary evolution in the representation of a part of History which is now losing its direct testimonies, those which made the documentary a privileged form. To be frank, Hazanavicius does not avoid certain errors of tastestarting with the tearful and omnipresent music of Alexandre Desplat.

However, it is difficult to doubt his good faith, his desire to question his system without rejecting it either. After all, this trajectory towards the explanation of horror can be deprived as the dialogue progresses, until an absolutely devastating finale, where the notion of reflection forces us to look, straight in the eyes, at what was the Shoah.