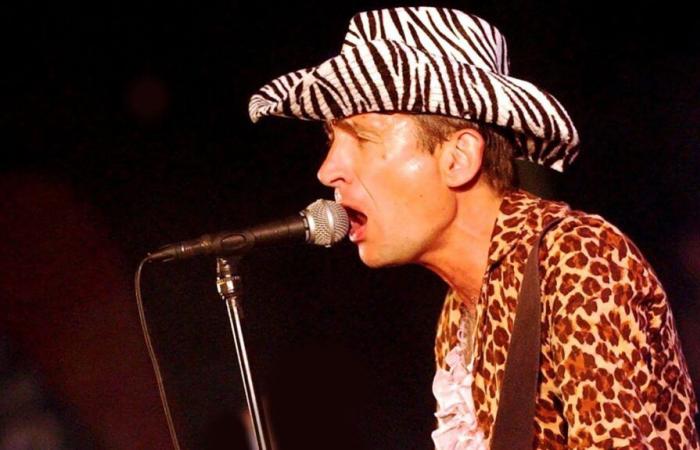

Colorful character, known for his flamboyant stage performances, certified bawler and amateur musician for eternity, author of a handful of hits, including Little girl et Manu ChaoDidier Wampas, 62, finally agrees to sit down at the table. In Workingman punkwritten with the complicity of journalist Christian Eudeline, he reveals his influences and his work, as well as the minimalist philosophy that underlies it.

“It’s the story of a rock kid who found himself in the spotlight and had to improvise”summarizes Christian Eudeline in the preface. “His career was built like this, without a pre-established plan, and without a desire for conquest (…) Didier is today the last original member, and in a certain way the guardian of the temple, the only master on board (…) And now, he has forty years of good and loyal service, around ten albums and almost a thousand concerts.”

In what we must call his memoirs, Didier Wampas, born in a “basic communist working family”talk cash. The lonely childhood that comes to warm up in adolescence the group of punk friends. The first concerts with Higelin, Bowie, disappointing at the Pavillon de Paris in May 1978, and the revelation in 1981 with the Cramps at Bobino, “the biggest shock of my life.” Not counting the Ramones, “the most great rock’n’roll band of all time” and Bijou, author with OK Carole “for best French rock album“.

In civilian life, there was first work in the factory for 18 months, then the job as an electrotechnical technician that his father found for him at the RATP, where he stayed for thirty years.because it was easy”. He maintained this job until the end, in parallel with his musical trajectory as a punk hero. But “I’ve always tried to do as little as possible.”he recognizes, a philosophy of the least effort assumed for those who do not “knew nothing about electricity” and still knows nothing about it, according to him.

This way of seeing things also applies to music. Didier became singer of Wampas by default: “Since I didn’t know how to play anything, I only had the microphone left.” He never prepares his texts. He usually comes into the studio empty-handed and sings whatever comes to mind. But be careful, it’s not about laziness. “I really like to wait until the last moment (…) I really feel like I’m lying to people when I rewrite my lyrics. It’s almost always the first draft, I don’t like retouching, reworking.”

As for the guitar, on which he has been composing since the suicide of Marc Police who wrote the music for the first three albums (from 1986 to 1990), he does not know how to play it anymore. Again, by choice. “It’s been thirty years and I still play with two fingers (…) I don’t want to learn to play better. (…) When it comes to composing, it’s not bad not to have technique.” And then “a song, if it’s too well recorded, it’s not worth it, it has to be true, it has to be dirty”.

After the death of Marc Police, “I wanted to do the show”he confides about the scene, where he is at his best, daring and giving his all. “When Marc was there, there was unity, I had neither the need nor the desire to put myself forward.”. After his death, “we had to react” (…) I felt obliged to act stupid.” With the communicative madness that we know.

At the 2004 Victoires de la Musique, with a pink boa around his neck, he ran down the stairs and jumped on stage, bawling “Wampas love you, Wampas don’t like other people, they don’t like Kyo and they don’t like the crappy variety!” – a great rock’n’roll moment.

However, don’t tell him he does comedy rock. He defends himself vigorously. “Funny rock, I never liked it. I don’t take myself seriously, but it’s not comedy rock. The goal is perhaps to make people laugh, but it’s more in the Trenet tradition”he analyzes. “With the Wampas, I wanted to do what the Cramps had achieved with American rock. We wanted to do yéyé punk.”

In his autobiography, we come across the entire small so-called “alternative” scene of the time –Black Berrier, Washington Dead Cats, Butcher Boys, which he speaks without tongue in cheek – around which the Parisian punk bands gravitated, but also the skins, who were not “no big fascists yet”. His punk philosophy is not synonymous with political commitment, and the Wampas have never been far left, he wants to emphasize.

Given that his furiously zany lyrics are often, more or less deliberately, hermetic, the primary quality of this book is to hear him decipher and recontextualize his songs one by one over the pages in a sort of commented discography. As one could imagine, Didier Wampas mainly nourishes his texts with things seen or experienced, “moments of life“. Thus, the lunar phrase “punks selling pancakes against abortion” (from the song Patrick) describes a scene he actually witnessed, during the 2004 Democratic convention in Boston (United States).

We learn, among a thousand other things, that he wrote The Bees in homage to Jonathan Richman of Modern Lovers, that the song I gave you my life was “a joke” in which he pretended to do Louise Attaque or that the title of the album The Wampas love you was a nod to the Beach Boys, of whom he is a fan, and to their album The Beach Boys Love You. But also that the song Manu Chaoa radio success which “everything changed” for the group, did not please the person concerned. Manu can be a good face, “The Wampas are proof that God exists.”

Didier Wampas “Worker Punk” (Harper Collins, 19.90 euros) was released on November 13, 2024