At a time of ecological transition, in partnership with the Urban Projects and Strategies Observation Platform (Popsu)diving into the projects and initiatives that move urban policies.

It should have been a project worthy of a work of science fiction: a city building 500 meters high, 200 meters wide, extending its glass walls 170 kilometers across the deserts of Saudi Arabia. “The Line”, presented in 2017 by the Saudi government, wanted to set the bar so high in futuristic dreams that we would soon have been forced to call a science fiction film that it was “worthy of The Line”. But show jumping is a risky discipline: sometimes, we get caught up in the bar of reality. According to Bloomberg, the city has been reduced to a barely more modest 2.4 kilometers. Between grandeur and decadence, this megalomaniac project offers lessons on the links between science fiction and regional planning.

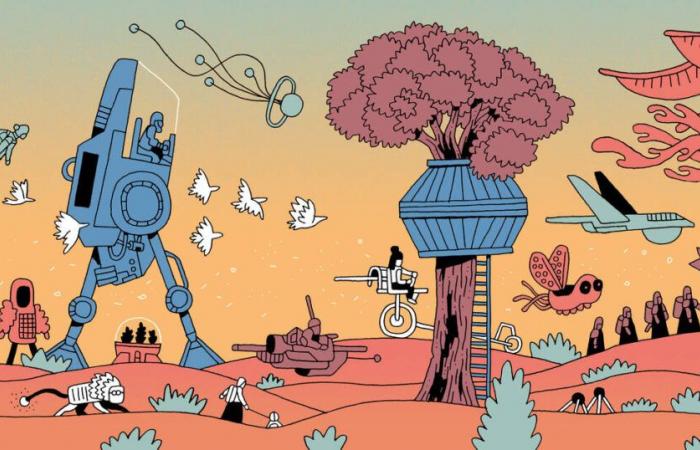

It was enough to watch the promotional video to convince yourself that the idea was born in a brain fed on Star Wars, At Fifth Element and to Avatar, in which the most pessimists will see the beginnings of Blade Runner : we follow a young girl floating in an ethereal city, all glass and cascading trees. And for good reason: its promoter, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Ben Salman, publicly says he is a fan of cyberpunk, a branch of science fiction exploring the hybridization between man and machine. He called on a whole bunch of Hollywood designers to design the city. “I’m not sure that the developers of Neom understand the deeper meaning of the message conveyed by these science fiction currents, remarked science fiction writer Chris Hables Gray, recruited for the project, to Socialter. They pump up the aesthetics of sci-fi to win the competition of who can build the weirdest thing.” The main idea came, for its part, from the group of Italian architects Superstudio, who had imagined in the 1960s a large bar of buildings surrounding the Earth to warn of galloping urbanization. Sixty years later, one of the members of the collective, interviewed by the New York Times about The Line, sighed: “Seeing the dystopia you imagined actually being built is not the best thing you could have dreamed of.”

“The fictional story is accessible to as many people as possible”

Like The Line, but in a less catastrophic way, fiction has become a reservoir of ideas for urban planners. The trend goes even further: it is the citizens themselves who are invited to become futurists to “imagine the city of tomorrow”. The invitation comes in the form of books, festivals, educational materials for children, and even board games. The Futurs Proches collective, which regularly organizes writing workshops at the request of cities and communities, has drawn up a small anthology of these “breaking proposals” given by citizens who are invited to express themselves on the subject: ecological transition income, reorganization of life in bioregions, individual carbon account, four-day week, right of enjoyment rather than property, majority judgment voting, food belts bordering cities, legal rights for living things… “The fictional story carries with it an advantage that is as simple as it is capital: it is accessible to the greatest number of people, observes Nicolas Gluzman, founder of Futurs Proches. No prior knowledge is needed to imagine and write stories. We’ve been doing it since childhood.”

During the Turfu Festival, an event combining science, research and participatory innovation in Caen, residents had, for example, to work on how to coexist with animals in the city. To clear the mind, there are multiple possibilities: completing a text from the start of a sentence, writing in “French”, a feminized version of the French language, drawing cards or dice… “It’s an extension of board games combined with writing workshops, which allow us to go beyond stereotypes,” observes Ariel Kyrou, essayist specializing in science fiction and author of Philofictions. Alternative imaginations for the planet (MF, 2024). For him, if these practices want to unlock their full potential, they must keep in mind a key element: knowing how far the journey should take in the future. “The best way to really project oneself into a territory is to play on a dialectic between the very long term and the immediate,” he advises. Imagine yourself three years from now, and you’ll probably still be stuck in your stereotypes; ship to 2050 or the year 3000, and your mind will then be fully unleashed. “We must then return to the here and now to ask ourselves: how can we do, today, to sow the first seeds that would make this dream a reality?” continues Ariel Kyrou.

For him, if fiction is a relevant tool for thinking about territories, it is in particular because it allows us not to be burdened with the truth. “In the times we live in, where there are fewer and fewer shared realities, with minimal confidence in a common institutional truth, intervening with a discourse of truth is complicated, not to say counterproductive; conversely, fictions make it possible to raise awareness of the fact that there are indeed alternatives, and they do so without claiming to be the truth.” For the journalist and writer, anticipation stories plunge us into the future to explore several different trajectories; in the same way as works by academics like In the beginning was… anthropologists and archaeologists David Graeber and David Wengrow (Les Liens qui Libération, 2021), showing that the past is not a long quiet river, open the door to a future teeming with tributaries. The process is not new: Rabelais used Pantagruel and Gargantua to convey messages which would have been censored by the temples of knowledge – the Sorbonne still belonged to the Church when he wrote, in the 16th century. Thomas Moore, for his part, described his Utopiaoften considered the first text of imaginative literature, such as a pamphlet. The same goes for Cyrano de Bergerac and his trips to the Moon.

“We see very quickly that the imagination is freed”

Fiction is today confronted with a paradox: the productions heirs to Utopia, which literally means “non-place”, or a place that does not exist, are today those which must contend with the territory as close as possible. However, these imaginations are loaded with politics: it is not enough to get involved in the game and dream to put aside all our biases, prejudices, and systems of oppression. Especially when the cultural productions that shape us – whether we think of Hollywood films or the great works of science fiction literature – were produced by a boy band of white, Western and wealthy authors. New branches of anticipatory literature explore other countries, more driven by decolonial reflections (we find there, for example, Afrofuturism) or ecological (this is the whole vein of ecofictions).

To prevent her writing workshops from leading to the creation of a new The Line, Kitty Steward has a “shield: plurality”. This writer, author of the Future in the plural: repairing science fiction (L’Inframonde, 2023), chairs the University of Plurality, which strives to diversify projections towards the future. Ketty Steward runs a writing workshop in Noisy-le-Sec, launched at the initiative of the department of Seine-Saint-Denis with the aim of giving a voice to populations who are not used to speaking out about the future. “We see very quickly that the imagination is freed, and that it is not confined by the shackles of blockbusters, she observes. Imagining what an appointment in the local public service might look like in a few years is also doing science fiction without realizing it.”

The facilitators of these foresight workshops, however, are keen to moderate enthusiasm: fiction should not be given more power than it really has. Especially when these workshops are set up to follow a trend and can lapse into “citizen-washing”, giving participants the illusion of building a future over which they will ultimately not have much influence. However, the issue is not there, for Kitty Steward: “What interests me is neither the final result nor even the final story: it is to have been able to play with people in telling each other stories”, she emphasizes. For her, the key is above all to show everyone that they are capable of writing a story, and therefore their own story: “I hope that they will leave with the desire to tell other stories and with the ability to recognize that the stories that we impose on them and that we claim to be reality are also stories.”