In “The Last Days of the Socialist Party,” he denounces the sabotage of the left by a handful of intellectuals complacent with the extreme right. Strongly criticized, especially by those who inspired him, Raphaël Enthoven at the forefront, the novelist invokes his right to satire.

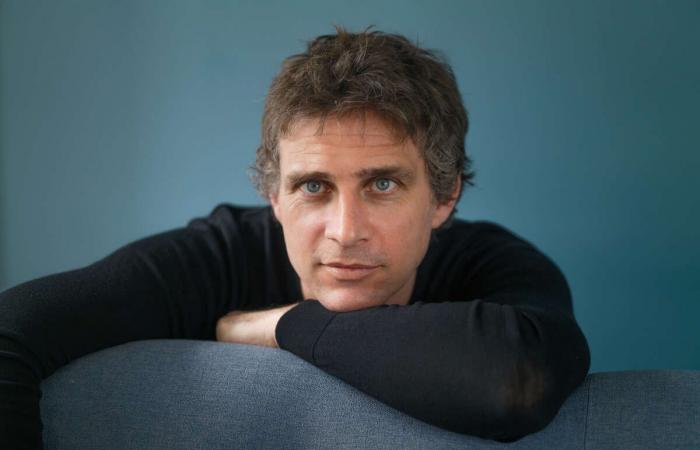

Aurélien Bellanger’s new novel was released on August 19 by Éditions du Seuil. Photo Bénédicte Roscot

By Caroline Pernes

Published on August 28, 2024 at 12:29 p.m.

Astormy weather on the literary rentrée. Released on August 19 by Éditions du Seuil, the new novel by Aurélien Bellanger, The Last Days of the Socialist Party, never ceases to be talked about. The cause? A truer-than-life story denouncing the sabotage of the left by a handful of intellectuals unscrupulous about joking with the extreme right. With a title redolent of controversy, the work already appeared, months before its release, in a strangely prophetic light. And, on the eve of the first round of the legislative elections, the author did not fail to clarify its purpose: “It will come out too late, alas, but I have written a book which tells how a heresy of the Socialist Party, the Republican Spring, surrounded by a small group of mediocre intellectuals, made possible the victory of the extreme right in France.”

At the beginning, The Last Days of the Socialist Party is a novel of nearly five hundred pages, the third published by Bellanger in less than two years. A great political-historical fresco, deliciously cynical, it follows the character of Grémond, an obscure apparatchik of the Socialist Party, taking advantage of the Islamist attacks of 2015 to impose himself on the front of the stage. Supported by two “philosopher [s] of plateau”, Frayère and Taillevent, he founded the December 9 Movement, and imposed an Islamophobic discourse in the public space under the cover of secularism, which would ultimately mark the ideological triumph of the extreme right. Any resemblance to reality is not fortuitous, the novel is crossed by a slew of easily identifiable characters.

Also read:

Aurélien Bellanger: “We are witnessing the sad defeat of critical thinking”

Thus, Grémond resembles in every way Laurent Bouvet, co-founder of the Printemps républicain, who died in 2021 of Charcot’s disease. The character of Taillevent, an ambitious philosopher walking his Don Juan airs in the streets of the Latin Quarter, is clearly inspired by Raphaël Enthoven, and Frayère, a hedonist “philosopher of the fields”, fits the description of his best enemy, Michel Onfray. Without forgetting the journalist Véronique Bourny, alter ego of Caroline Fourest (co-founder of the magazine Free-Shooter with Enthoven), Emmanuel Macron, known as “the Canon”, and finally Bellanger himself, disguised as the character of Sauveterre. Even Manuel Valls is in the game – under his real name.

“The right to exaggerate”

Praised by a part of the left, the work is now under fire from critics, as if fiction were called upon to account for reality. But can we still talk about fiction? Raphaël Enthoven, taking on the character of Taillevent and the associated description of “mediocre intellectual” at face value, has chosen his side, and has sent out a few tweets denouncing “the abject necrophiliac and lying last book of Aurélien Bellanger”. In a long interview with L’Express, he denounces the inconsistencies of a novel telling “absolutely anything”. The proof: The Last Days of the Socialist Party places his meeting with Onfray at a time when they had in reality stopped speaking to each other.

Asked about this on France Inter by Sonia Devillers, Aurélien Bellanger justified himself: “These are liberties that we can take […] : use existing figures, transform them into phantasmagoria, exaggerate, use satire. [Ce sont] arguments to try to tell something about the spirit of the times.” A novel with keys traversed by barely encrypted ghosts of the present, The Last Days of the Socialist Party he claims, as Raphaël Enthoven maintains, “tell what really happened” ?

Certainly, the work is openly political – the author explains that he wanted to write an investigation into the decay of an anti-racist left, but does not hide his satirical intentions: “The novelistic investigation is interesting because we actually have rights, poetic licenses that we would not grant to other scientists, but which allow us to tell something differently. And actually, I abuse this right, which is the right to satire, the right to exaggeration.” “This is a big tweet,” concludes Sonia Devillers. We will leave it to the reader to judge.